Dr Des Corrigan on why over one-third of drug clinic patients are prescribed benzodiazepines

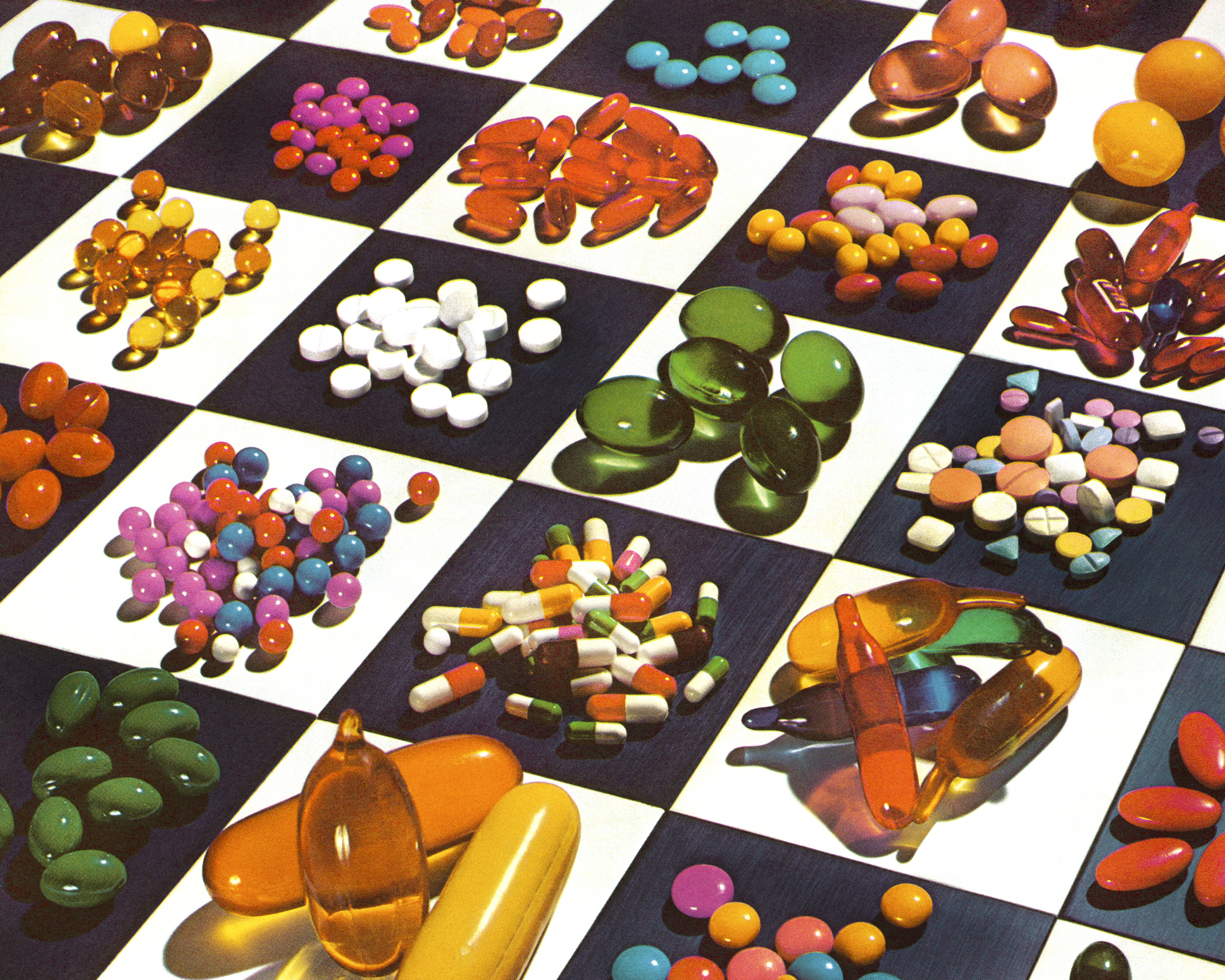

Department of Health guidance on prescribing benzodiazepines (BZDs) to problematic opioid users date back to 2002 and are full of common sense. They clearly state that “prescribing benzodiazepines to opioid users (and other drug users) should be seen as exceptional rather than a routine clinical decision”. If only prescribers of all types had complied with that advice, we might have been spared the hundreds of poisoning deaths involving combinations of BZDs and other drugs which have occurred over the intervening 17 years. If only!

Much of the narrative around the benzo issue, as articulated to me by drug users and by frustrated workers in community drug projects, centres on alleged inappropriate prescribing by certain allegedly ‘rogue’ GPs. It came as a bit of a shock to read, in a recent paper in the Irish Journal of Medical Science from the laboratory staff at the National Drug Treatment Centre Board (NDTCB, but known widely as ‘Trinity Court’), that 36.5 per cent of patients attending that clinic had been prescribed BZDs (mainly diazepam) by the staff of the clinic. It is no wonder, therefore, that 74 per cent of clinic attendees tested positive for BZDs when tested in October 2018.

The laboratory can now identify up to 31 BZD-type drugs. Because many individual BZDs have common metabolites, ie, those of diazepam are oxazepam, nordiazepam and temazepam, with the first two also metabolites of chlordiazepoxide, this makes it difficult to determine which parent drug or drugs were actually consumed. Of the 200 samples analysed by LC-MS, the researchers believe that the main drugs used are probably diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, temazepam and alprazolam. It is also clear that those testing positive for a BZD are polydrug users, since 93 per cent of the sample were positive for a methadone metabolite, 55 per cent for cannabis, 41 per cent for opioids, and 33 per cent for cocaine. Alprazolam is one of the BZDs that can be unambiguously identified and 66.5 per cent of those tested were positive for it. It is not, however, prescribed in Trinity Court, indicating either prescribing by other doctors or use of illicitly obtained prescribed alprazolam or of counterfeit Xanax ‘bars’.

Another BZD that can be identified directly is etizolam, which was detected in a small number of samples. Etizolam is one of 23 designer benzos under active monitoring by the European Drugs Agency (EMCDDA) based in Lisbon. Another name for these are ‘new psychoactive substance-BZDs’, or ‘NPS-benzos’. Some, such as etizolam, are sold under their own names but others are used to formulate fake versions of diazepam and alprazolam for sale on the black market. Etizolam is believed to be the most commonly-seized BZD in the EU. Most seizures appear to involve material sourced in China, imported into the EU and tabletted by criminal gangs for sale either as etizolam or as fake diazepam or fake alprazolam ‘bars’. Sometimes it appears on the black market soaked onto blotting paper, in the same way that LSD was sold years ago. In the UK, what were supposed to be etizolam tablets have been found to contain alprazolam, flubromazepam (another NPS-benzo) and another designer drug, the stimulant but cardiotoxic diphenylprolinol (D2PM), according to an independent drug-testing laboratory, initially set up to analyse and provide information on the actual composition of ecstasy and other tablets as a harm-reduction measure.

Etizolam was first patented in 1978, so it is hardly a ‘new’ drug, even though it was not detected as a street drug in Europe until 2011, leading to it being described as an NPS-benzo. It is a licensed medicine in Japan (since 1983), India and Italy, where it is used to treat generalised anxiety disorder with depressive symptoms, for its strong muscle relaxant properties and as a replacement therapy in the treatment of alcohol dependence. It is not licensed in Ireland or in other EU countries except Italy. The chemical structure of this thienodiazepine makes it different to the classical benzodiazepines but pharmacologically, it is similar, with agonist activity at the GABA Type A receptor. It is a short-acting benzo with a half-life of six hours, though as with diazepam, poor CYP2C19 metabolisers will have an extended half-life. The dose range is 0.25-3mg, compared to 2-5mg for diazepam, leading to street claims that it is five times more potent than diazepam. Claims for increased potency of etizolam and other newer drugs, including notoriously the designer fentanils, are beloved of the sensationalist media. Unfortunately, these media reports also increase the attractiveness of the drug for street users and can lead to a spike in interest in and use of the drug in question in the search for a stronger ‘buzz’ or ‘turn-on’. Etizolam is a typical BZD in its clinical effects and in the withdrawal symptoms that occur when a regular user ceases use. These include palpitations, impaired sleep, agitation and tremors.

The risk of death when etizolam is combined with other CNS depressants is also similar to other BZDs. One of the first overdose cases was reported in the Annals of Emergency Medicine in 2015. A patient, believed initially to have taken heroin, was brought into an emergency department, unresponsive. He was initially given naloxone, but sedation persisted. He was then given flumazenil IV, which produced an immediate and complete reversal of sedation. Laboratory analysis confirmed that both heroin and etizolam had been consumed. The first recorded deaths were reported from Japan in 2008. In Ireland, there were no deaths involving etizolam reported in 2015, but seven the following year and six in 2016. The latter figure compares to 46 deaths linked to alprazolam, 42 to flurazepam and 96 to diazepam in the same year. On the face of it, therefore, etizolam is of lesser concern but it would be unwise to be complacent, because there were nearly 300 etizolam-related deaths reported from Scotland in 2017, indicating that this drug has the potential to spin out of control rapidly.

It is clear from the NDCB paper and the data from the EMCDDA that we face a challenge from not only the traditional medicinal BZDs and related Zed drugs, but also increasingly from an array of unlicensed BZDs now being released by organised crime gangs with access to tabletting equipment. The recent pronouncement by the Medical Council that it will investigate inappropriate over-prescribing of BZDs, Zed drugs and indeed pregabalin is a welcome, if long overdue, response to a significant public health problem involving licit BZDs. This needs to be matched by a commensurate approach to the supply and use of the illicit molecules.