The societal effects of Covid-19 have taken a significant toll on people’s mental health, writes Eamonn Brady MPSI

2020 has seen an increase in anxiety disorders due to restrictions, reduction in social contact, worry about health, worry about livelihoods and the many other negative impacts of Covid-19.

Introduction

Elevated levels of anxiety or worry regarding an exam, job interview or a test, (ie, driving test) would be considered ‘normal’. Ask a professional stage actor, ‘do you get nervous before a performance?’ and they would say they would be worried if they did not.

Our natural anxiety response in these perceivably stressful situations helps maximise performance. In general terms, people are natural worriers. Anxiety is experienced by everyone at some time or another.

So, when does ‘worrying’ or our natural anxiety become an ‘anxiety disorder’? It is when our normal reactions and responses become excessive, persistent, and debilitating. When worrying and feelings of anxiety become uncontrollable and ever-present, to the point that they take over and interfere with everyday living, this then is what is known as generalised anxiety disorder, or GAD, the most common type of anxiety disorder.

Overall, anxiety disorders include:

GAD

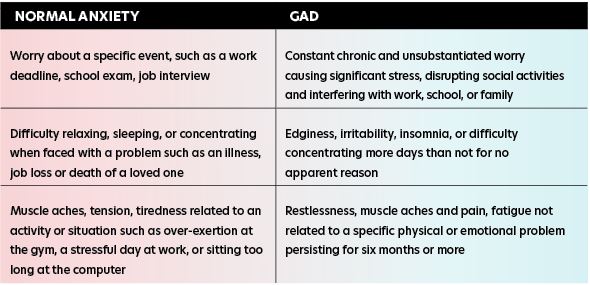

The table on p47 highlights the main differences between ‘normal’ anxiety and GAD. GAD can significantly affect daily life, making it difficult to perform normal everyday tasks. If left untreated, it can have a significant impact of relationships with family and friends.

In Ireland and throughout Europe, anxiety disorders are the most common mental health problem, along with depression. They account for similar levels of stress and disability within society as cancer or heart disease.

Whilst there are no accurate figures regarding the extent of the condition in Ireland, it is estimated that 11 per cent will suffer a primary anxiety disorder at some point in their life. GAD is most common in people in their 20s. It affects approximately 5 per cent of adults (slightly more women than men).

A ‘primary’ anxiety disorder is defined as one where anxiety is the primary problem. Symptoms, occurring independently of other mental problems, follow a set pattern over a longer period, perhaps months or years. Whilst they exist, problems can be heightened when coupled with other challenging life situations.

Anxiety can be defined also as a ‘secondary’ problem, where it is a symptom of another disorder associated with elevated levels of anxiety (ie, depression and/or substance or alcohol misuse). In these cases, most benefit comes from treating the underlying problem and not simply the anxiety itself.

Patients with anxiety disorders often seek treatment from primary care providers (PCP). They may present with medically unexplained symptoms, making identification of the correct diagnosis a challenge.

Causes

As is the case with most mental health conditions, the specific cause of GAD and other related anxiety disorders is not known. Whilst some understanding relating to individual disorders exists, a person could develop GAD for no apparent reason. Researchers believe the condition is caused by a combination of factors, including:

- The body’s (and more specifically, the brain’s) biological processes.

- Genetic factors.

- The person’s environment.

- Life experiences.

Primary anxiety disorders are thought to result from a combination of genetic predisposition and life stress triggering a vicious cycle. Chemical reactions in the brain (imbalance of neurotransmitters, particularly serotonin and noradrenaline) can significantly affect mood. This, along with other factors like distorted thoughts and beliefs about risk and danger, combined with changing patterns of behaviour, such as avoidance or safety-seeking, all interact to develop and exacerbate the problem.

It is estimated that up to 90 per cent of persons with GAD experience one or more comorbid psychiatric diagnoses. An American study by Stein and co found that in patients with PTSD, major depression is seen in 61 per cent of patients, GAD in 39 per cent, social phobia in 17 per cent, PD in 6 per cent, and substance use disorders in 22 per cent of patients.

GAD symptoms

Symptoms often develop slowly, so it can be the case that the signs are simply not recognised, as small adjustments are made along the way to compensate. Symptoms can vary in both severity and number, depending on the individual circumstances.

The person may become withdrawn, pulling back from social and family gatherings as a way of avoiding negative feelings. Working life too can become increasingly stressful, perhaps resulting in time off due to ‘illness’.

Psychological symptoms include:

Restlessness, a sense of dread and foreboding, constant edginess, poor concentration, easily irritated, lack of patience.

Physical symptoms can include:

Dizziness, chronic tiredness, palpitations, aching muscles, dry mouth, excessive sweating, shortness of breath, stomach ache, nausea, diarrhoea, headache, excessive thirst, difficulty falling asleep, insomnia. A major step in treating GAD is acknowledging a problem and then doing something about it. The first port of call should be a GP. Generally, there are two main treatment types for GAD:

- Psychological therapy.

- Medication.

Treatment may be either of the above, or perhaps a combination of both. The most common advice for those diagnosed with GAD is to consider psychological therapy first before going down the medication route.

Other anxiety disorders

OCD

OCD is an anxiety disorder in which people experience unwanted and intrusive thoughts (obsessions) and feel compelled to repeatedly perform routines (compulsions) to ease anxiety. It is estimated that one-in-10 people will experience some form of OCD during their lifetime.

Common obsessions include:

- Fear of illness, especially a terminal illness.

- Irrational fears regarding poor hygiene and cleanliness.

- Anxiety that aggressive thoughts/impulses become reality.

- Fears of harming a loved one or oneself.

- Excessive preoccupation with the order, arrangement, or symmetry of things.

- Intrusive words or sounds.

- Fear of losing valuables.

Compulsions

In most cases, compulsions are triggered to manage the anxiety brought on by the ‘obsession’. Occasionally, compulsions appear without the obsession attached. In a similar way that a coffee drinker’s tolerance to the effects of caffeine increases the more they consume, the same is true with compulsions; the more the ritual is performed, the less effective it becomes; therefore, frequency is increased, with increasingly less effect.

Common compulsions include:

- Excessive personal hygiene rituals, especially hand-washing.

- Checking and rechecking objects, information.

- Repetitive actions, ie, touching, counting.

- Repeating a name or phrase or tune.

- Arranging and ordering, ie, items in a room, furniture, books, etc.

- Hoarding things.

OCD is an extremely complex disorder. Sufferers are constantly in a ‘state of alert’ regarding potential harm and threats. They often see themselves as solely responsible for protecting people, especially close family, from external harm.

PD (panic disorder)

Panic attacks can be extremely alarming events. Typically, an attack will occur without warning and for no obvious reason. The panic reflex is deployed by the body in response to a perceived threat which does not exist. At the onset of an attack, acute severe anxiety/panic ensues and adrenalin is released throughout the body. Attacks can include:

- Irregular breathing.

- The need to escape.

- Feeling of imminent danger or doom.

- Palpitations, pounding heartbeat.

- Chest pain.

- Dizziness, light-headed or faint.

- Sweating.

- Trembling or shaking.

- Ringing in the ears.

- Hot or cold flushes.

- Fear of losing control.

- Fear of dying.

Commonly linked with agoraphobia, up to two-in-10 people will experience some form of panic episode during their lifetime.

Social anxiety

Excessive levels of anxiety in social situations or performance situations, such as presenting or talking to groups.

Those with this disorder become adept at developing and employing subtle strategies that help them avoid or hide from social gatherings. More than 12 per cent of people will be affected by social anxiety issues at some point. Whilst onset is most frequent in adolescence, this disorder can occur at any time. Physical symptoms can include blushing, sweating and palpitations.

People with social anxiety may:

- Be overly self-critical of the smallest error.

- Find blushing as painfully embarrassing.

- Feel their actions are constantly under scrutiny.

- Be submissive when talking with more ‘powerful’ people, ie, employer, supervisor, etc.

- Avoid using public toilets.

- Fear of talking or presenting in front of a group.

Treatment options

Psychological therapy

Although psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy have been shown to be individually effective, studies consistently demonstrate that combination treatment gives superior results compared with either treatment alone.

CBT

One of the most effective types of treatment for GAD and other anxiety disorders is CBT (cognitive behavioural therapy). CBT, proven to give full recovery from GAD in up to 50 per cent of cases, is a type of talk therapy that targets the anxiety and associated behaviours in a collaborative way. Attending weekly one-to-two hour sessions, CBT helps the patient learn to identify negative thinking patterns and their triggers and replace them with positive ones.

Through learning how the cycle of anxiety works and how to challenge unhelpful beliefs and applying the new skills and techniques learned during therapy sessions, patients can regain control of previously lost situations. Learning how to deal with ‘today’ rather than ‘yesterday’ is also a valuable tool when creating a positive enabling environment. The skills and techniques need to be practised between sessions so that they become embedded and remain there for life.

Whilst the programme duration itself is relatively short-term, typically around 12-to-16 weeks, the benefits and sense of stakeholding in their own outcome the patient derives from participating is very much long-term.

Psychological therapy is the preferred route initially in most cases. It may be the case, however, that dependent on the severity of the case, a combination of therapy and medication offers the best results. Serotonin-boosting medication can help ease anxiety, thereby enabling the patient to get more from their therapy sessions.

Exposure therapy

A form of CBT and as the name suggests, the patient is exposed to a feared situation. This can prove particularly effective with those suffering with specific phobias. This treatment can also be used as a precursor to regular CBT therapy. If the level of anxiety is too high, starting with regular CBT may be ineffective. Exposure therapy can help reduce sensitivity to a situation or event.

Applied relaxation therapy

Applied relaxation is a different type of psychological treatment. Developed initially in the treatment of phobias, it is now more widely used to treat other anxiety disorders, including GAD, and is as effective as CBT.

Application focuses on relaxing the muscles when potentially anxious situations occur. The methods used are taught by a trained professional over three-to-four months and include:

- Learning special techniques to relax muscles.

- Learning how to implement the techniques quickly and in response to a trigger, thereby enabling use in situations that cause anxiety.

Medication

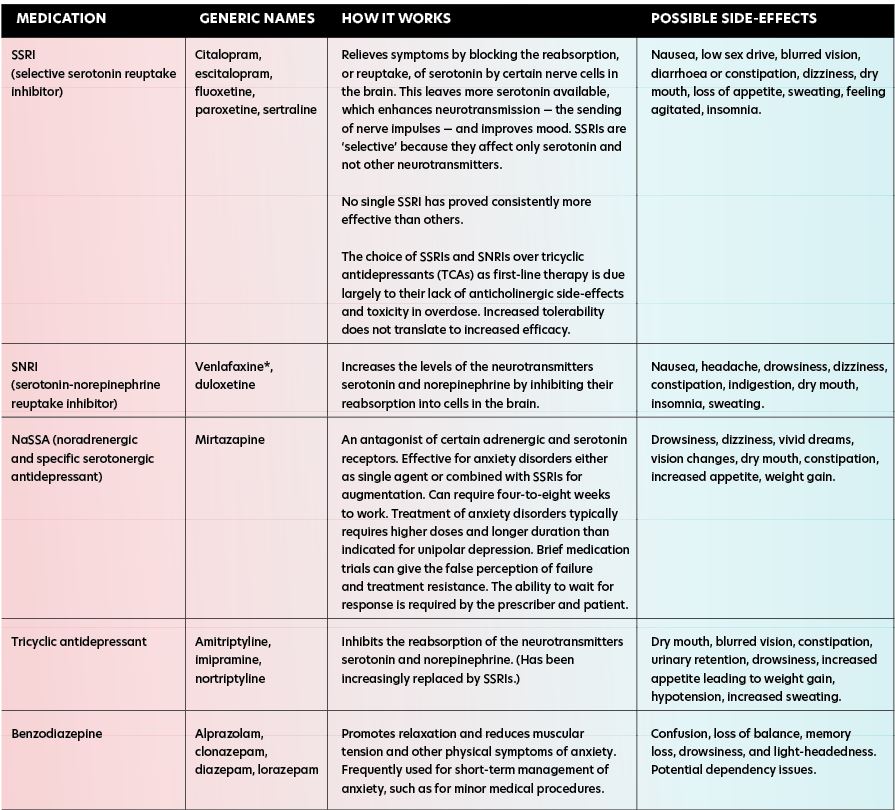

The table opposite outlines the main classes of medications for the treatment of anxiety disorders.

Anxiolytics

Anxiolytic medications are the second set of medications for treatment of acute anxiety, with antidepressants being the first set. These medicines abort current symptoms of anxiety and do little to prevent symptom recurrence. Anxiolytics can be divided into benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepines.

Benzodiazepines are frequently thought of as the ‘classic’ anxiolytic. This class of medication provides a wide range of choices in terms of onset of action, half-life, and the presence of an active metabolite. There are no specific recommendations in terms of use of one benzodiazepine over another in the treatment of anxiety disorders. In general terms, benzodiazepines with shorter half-lives and more rapid onset of action are more likely to lead to rebound anxiety when the effects of the medication wane, leading to a need to take more of the medication. If possible, longer-acting benzodiazepines (ie, clonazepam) should be used in conjunction with antidepressants when the prescriber needs to decrease anxiety acutely, to allow for treatment engagement, and/or treat symptoms that are threatening patient safety.

If possible, treatment should be limited in duration and stopped once antidepressants lower overall anxiety levels and patients are able to engage in other forms of treatment. Although benzodiazepines are effective, physiologic dependence develops in all users, so misuse poses potential problems.

Tapering benzodiazepines must be gradual and can be dangerous if completed too abruptly. The withdrawal syndrome that accompanies benzodiazepine cessation closely parallels that of alcohol withdrawal. The mildest form is rebound anxiety that can be seen with reducing or missing doses and is most common with short-acting benzodiazepines (ie, alprazolam). In rare cases, severe withdrawal symptoms can be seen, which can lead to seizure, coma, and death.

Although exact rates of risk are unknown, severe withdrawal is rare and more likely in patients taking higher doses for prolonged periods, and for whom the medication is discontinued abruptly. Co-occurring substance use disorder is common and in such situations, treatment with benzodiazepines is contraindicated.

When anxiety needs to be controlled acutely, but benzodiazepines are not indicated, there are other alternatives. The anticholinergic agent hydroxyzine, b-blocker propranolol, gabapentin and pregabalin are effective alternatives as anxiolytics without abuse potential.

Other medications

Antihistamines: Whilst usually prescribed to treat allergic reactions, some are used to treat anxiety short-term, as they have a calming effect, helping lessen feelings of anxiety. Hydrazine is the most prescribed for treating anxiety.

Pregabalin: May be offered if SSRI or SNRI are not suitable. Although prescribed for epilepsy, has been found to be beneficial for anxiety.

Buspirone: Can help ease psychological symptoms. Belongs to group of medicines known as anxiolytics. Usually taken for at least two weeks before any improvement noticed. Works in a similar way to benzodiazepines.

Condition-specific medication treatment recommendations

GAD: Daily SSRI/SNRI. Anxiolytics may be needed as a bridge for severe symptoms until antidepressants provide relief.

PD: Daily SSRI/SNRI. Use long-acting anxiolytics, because short-acting agents are unlikely to abort panic attacks.

OCD: Daily SSRI/SNRI. Anxiolytics may be needed as a bridge for severe symptoms until antidepressants provide relief.

Social anxiety disorder (SAD): Daily SSRI/SNRI. Propranolol is useful for public speaking.

PTSD: Daily SSRI/SNRI. Anxiolytics may be needed as a bridge for severe symptoms until antidepressants provide relief. Benzodiazepines are generally not recommended.

References on request