Eamonn Brady MPSI takes a clinical look at headaches, including how to distinguish the different types and how to treat the resulting pain

One of the most important first steps in the successful management of headache is diagnosing whether migraine ‘is’ or ‘is not’ the cause of the headache. Migraine is quite distinct from other headache types in how it presents and in how an episode evolves, attacks, and subsides.

I discuss both ‘non-migraine’ and ‘migraine’ headaches to help distinguish between both and the treatment options for both, considering many painkillers are used for both types. Secondary headaches are a common problem; secondary headaches are headaches caused by other medical conditions or medication. Medication overuse headaches are a significant problem and are often associated with codeine overuse and addiction.

A. Non-migraine headaches

- Tension headache

The most common type of headache is tension headaches and these are usually caused by stress, poor posture, or inadequate lighting. Often beginning in the afternoon or early evening of a stressful day and presenting as a ‘band-like’ or ‘pressing’ sensation at the front of the head, they can last from one-to-six hours.

With tension headache, pain tends to be bilateral (both sides of head), constant and with no other symptoms as opposed to migraine, which is usually confined to one side of the head, together with other identifiable symptoms.

For most, treatment with an analgesic (paracetamol, aspirin, or ibuprofen) usually takes care of it. Engaging in self-management activities such as regular exercise, regular eye breaks from the computer at work, sensible eating habits and learning stress management techniques can all lead to a reduction in tension headaches.

2. Chronic daily headache

Different from tension headache, which is episodic in nature, chronic daily headache (CDH) refers to any headache that occurs on at least 15 days per month, with each at least four hours’ duration. Currently affecting 4-to-5 per cent of the population (and growing), variants of CDH can significantly affect an individual’s ability to function at work, at home and socially.

There are three distinct types:

Chronic tension headache

Typically affects those with a history of ordinary tension headache and whilst similar, it occurs on at least 15 days per month. Whereas tension headache is usually related to individual situations, chronic tension headache tends to be provoked by more enduring ongoing personal situations, ie, job issues, family and relationship problems, grief, and/or depression.

Chronic (transformed) migraine

Diagnosed if you have migraine on 15 or more days a month over a period of at least six months. Over time, people with this diagnosis may experience an additional daily or almost-daily headache. As the frequency of these headaches increases, there is a corresponding decrease in actual headache pain, along with other migraine symptoms. The downside of this perceived relief is that the headaches become less responsive to treatment. With other effects such as depression and sleep disturbance, people will usually experience a more typical ‘breakthrough’ migraine attack on top of the enduring ‘background’ headache. See more on migraine later.

Medication overuse headache

This is caused by the overuse of medication, taken primarily to alleviate headache. In the main, this relates to analgesics (paracetamol, aspirin, ibuprofen, but with codeine being the worst culprit) although it can also occur with migraine-attacking drugs (triptans). Those most commonly affected are those with a history of tension headaches or migraines that have become more frequent or severe over time. They take medication to gain relief from the pain, only to find the headache returning once the drugs have worn off.

Sufferers then take more medication to alleviate continued pain, pain eases, drugs wear off, pain returns, etc (a vicious circle). It becomes easy then to fall into a cycle of taking medication for a headache that is itself caused by medication. Once in this spiral, the only way to break the cycle completely is through withdrawal. This is best achieved through consultation with a doctor. Typical withdrawal side-effects can be worsening headaches, nausea, and anxiety for a couple of weeks.

3. Cluster headache

Affecting around 1 per cent of people, this is a rare but very severe headache found six times more commonly in men and usually begins in the late 20s or early 30s. Typically, attacks begin in the middle of the night. Primary symptom is a severe stabbing pain affecting one side of the head. The side affected can vary between attacks, but only in very rare cases would it affect both sides of the head at the same time. The duration of an attack can be between 15 minutes and up to three hours. Attacks come in clusters (hence the name) and can occur several times a day over a period of weeks or even months. After each cluster though, attacks can disappear for months or years.

The three ‘primary’ types of headaches described above are the most common non-migraine headaches

A cluster attack can be distinguished from a migraine attack, in that with cluster headache, the person is agitated during an attack or unable to sit or lie at peace or find relief through sleep. During an attack, other symptoms may occur, such as red or watery eyes, runny nose, nasal congestion, or facial sweating. In addition, a sufferer’s eyes may be affected, with constriction of the pupil or drooping or swelling of the eyelid. Cluster headache has been described by some medics as ‘the most painful event that can happen to a person’, which emphasises the severity of the condition.

Whilst the cause is unknown, suspected trigger factors include alcohol, tobacco, irregular sleeping patterns, stress and decreased blood oxygen levels. The most common treatment for cluster headache is the inhalation of pure oxygen and is only successful if the mask fits perfectly without leaking. The three ‘primary’ types of headaches described above are the most common non-migraine headaches. There are other types of headaches, ie, those relating to sinus problems, over-exertion, especially exercise. These are known as secondary headaches.

B. Migraine

I discussed migraine in detail in Irish Pharmacist earlier in 2021, so for the purposes of this article, I will only touch on its symptoms and types without going into detail on causes.

Common symptoms and types

The word ‘migraine’ derives from a Greek word hemikrani (half-skull), which literally means ‘pain on one side of the head’. This accurately describes and differentiates migraine from other types of headaches as typically, it presents on one side of the head. An attack may consist of some or all the following symptoms.

Migraine without aura (around 80 per cent of all attacks):

- Moderate-to-severe pain, throbbing one-sided headache, aggravated by movement.

- Nausea and/or vomiting.

- Hypersensitivity to external stimuli (ie, noise, smells, light).

- Stiffness in neck and shoulders.

- Pale appearance.

- Migraine with aura (in addition to above symptoms):

- Aura, around 20 per cent experience visual disturbances prior to the headache lasting up to one hour (most commonly blind spots, flashing light effect or zig-zag patterns; may also include physical sensations such as unilateral pins and needles in fingers, arm and then face).

- Blurred vision.

- Confusion.

- Slurred speech.

- Loss of co-ordination.

Other types:

Basilar migraine

Usually affecting teenage girls, this is a rare form of migraine that presents additional symptoms such as loss of balance, fainting, difficulty speaking and double-vision. There can be loss of consciousness during an attack.

Hemiplegic migraine (sporadic or familial)

Usually beginning in childhood, this severe form of migraine causes temporary unilateral paralysis. May also feature extended aura period that could last for weeks. Generally related to a strong family history of the condition. It is a rare form of migraine; diagnosis usually requires a full neurological exam as the symptoms may be indicative of other underlying conditions.

Ophthalmoplegic migraine

In addition to headache, this very rare form of migraine shows additional symptoms, such as dilation of the pupils. Inability to move the eye in any direction, as well as drooping of the eyelid occurs. It occurs primarily in young people and is caused by weakness in muscles which move the eye.

Abdominal migraine

Symptoms are usually nausea and stomach-related rather than headache. Occurs predominantly in children, usually evolves into typical migraine with age.

Migraine triggers

A myriad of trigger factors, whilst in themselves not the cause of migraine, can build, bringing an individual to the point where a migraine attack is imminent. Again, these can be different for everyone and indeed, may differ for an individual each time, depending on their situation; trying to track down specifics can be difficult. The most common triggers include:

Environmental factors

Just moving around doing normal day-to-day things that would usually not cost a second thought can be a potential danger for someone susceptible to migraine:

- Bright or flickering lights (could be cinema, shop displays or sunlight through trees whilst driving).

- Certain types of lighting (fluorescent, strobe).

- Strong smells (especially perfume, paint, etc).

- Weather (variety of factors, ie, bright sun glare, muggy close days, humidity).

- TV/computer screens and monitors.

- Loud and persistent noise.

- Travel areas of pressure change, ie, altitude.

Dietary triggers

Research indicates about 20 per cent of migraine attacks are brought on by dietary factors. Whilst people believe this to be the case, actual scientific evidence proving a link is virtually non-existent. In many cases, there may be other factors that precede consuming a ‘suspect’ food that could contribute more to the onset of an attack, ie, lack of sleep, skipping meals. The most-cited link is foods which are high in the amino acids tyramine and/or phenylethylamine, such as:

- Cheese (fermented, aged, or hard mouldy types).

- Chocolate.

- Alcohol (beer and red wine particularly).

- Nitrites (common in processed meats).

- Sulphites (ie, preservative in dried fruit and red and white wine).

- Additives (MSG).

- Aspartame (diet drinks).

- Caffeine (coffee, tea, etc; although caffeine can be used to prevent migraine, it is down to personal tolerance).

Hormonal triggers

Once females move into puberty and then adulthood, hormones play an increasing role in migraine prevalence. Oestrogen fluctuations due to menstruation or using oral contraceptive pills or HRT can sometimes trigger migraine. Conversely, migraine susceptibility can decrease during pregnancy when oestrogen levels are high.

In the main, migraine attacks lessen post-menopause (although can increase in the years preceding it).

Identifying triggers can be the single most important step an individual can take in helping themselves to manage their condition. A diary noting possible triggers — including diet, sleep and other events, including symptoms — is important when seeing a doctor and seeking treatment, as it will help the doctor better identify the type of migraine (or if it is even migraine) and help manage treatment. It may not be necessary to avoid situations completely, but instead build levels of awareness so that appropriate preventative steps and actions can be taken.

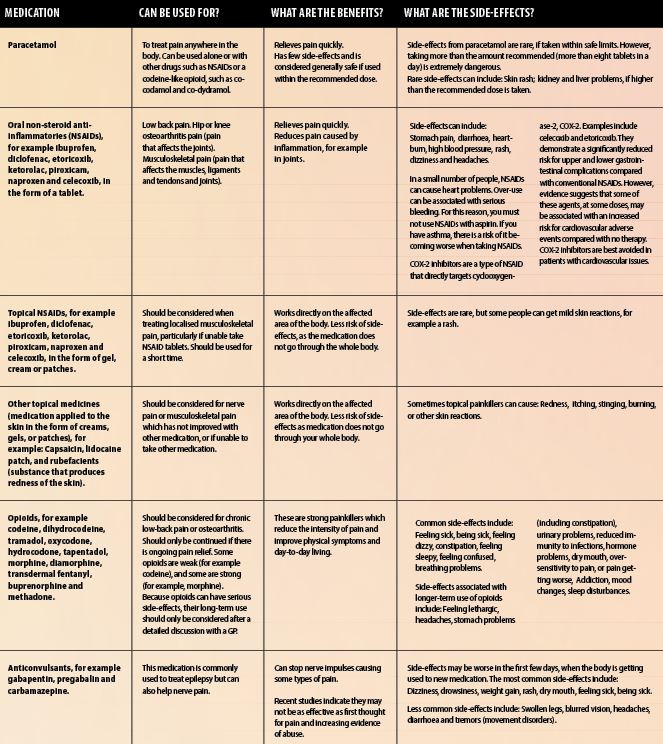

C. Medication

A successful outcome from pharmacist and GP visits should be a pain management plan. It is highly likely that as part of this, some form of pain-relieving medication will be part of the treatment plan. Ideally, advise on promotion of self-help, self-management, and other treatments to help improve their condition and add value to the benefit offered by medication. Given the wide and varied nature of chronic pain, there can be a myriad of medication options. The effectiveness of medication depends on the nature and severity of the pain. It is important that non-medication management options are considered, including exercise, relaxation therapies (especially for the likes of tension headaches), physiotherapy and cognitive behavioural therapy, just to name a few.

Regarding treatment of chronic pain caused by migraine, in addition to standard paracetamol and NSAIDs, triptans are considered the most effective to combat acute attacks if ordinary analgesics do not work.

These include:

- Almotriptan.

- Frovatriptan.

- Sumatriptan.

- Zolmitriptan.

- Eletriptan.

- Naratriptan.

All are POM, apart from sumatriptan, with an OTC version recently becoming available in Ireland.

Preventative medication for migraine

I previously discussed preventative medication for migraine in Irish Pharmacist so for this article, I only give a quick summary of the preventative options. Prophylactic medication may be considered if the patient has taken adequate lifestyle steps to prevent migraine, such as using a diary to determine triggers and avoidance of these triggers, but the migraine continues. It would be reasonable for a prescriber to consider prophylaxis for migraine if a patient must use analgesics for eight or more days of the month.

Prophylactic medication should be tried for four-to-six months at a reasonable dose to determine if it is working effectively. Prophylactic medication has potential side-effects that can limit dose or use. Amitriptyline, topiramate and flunarizine are the three most prescribed migraine prophylactic drugs, with amitriptyline being the most prescribed. Other prophylactics such as sodium valproate, pregabalin, gabapentin and pizotofen are considered second-line (often only used if the first three are not tolerated or ineffective).

The pharmacist’s role

It is not just about medication, although regular review of the continued suitability of all medications used by those with chronic pain is vital. For many, the pharmacy is becoming the first port of call when a health problem, especially pain-related, arises. Using some of the ideas regarding questions, pain diary, etc, will really help in enabling people to make better-informed decisions about their own next step. Becoming familiar with local resources, like physios, support groups, condition-specific charities and signposting these will only add value to a positive perception.

References on request