Helping patients to stop smoking will be one of the most common tasks for pharmacists this January and beyond.

I previously discussed smoking cessation in Irish Pharmacist and for the purpose of this article, I will concentrate on OTC medication to help give up rather than the negatives effects of smoking, which are well known to health professionals and the public alike. As a pharmacist, its rare to read through the causes of any condition that does not have smoking listed as one of the causes or exacerbating factors, so the benefits of giving up from a health perspective are obvious.

Three steps to giving up

Deciding to give up smoking and really wanting to succeed are important steps in becoming a non-smoker. There are three steps to giving up smoking:

- Preparing to stop;

- Stopping; and

- Staying stopped.

It can take up to three months to become a non-smoker, but it usually takes less time. The physical craving for a cigarette often disappears in less than a week, but the psychological craving can last longer.

Step 1 – Preparing to stop

It is important that people stop smoking because they want to. Think of the many benefits gained by stopping smoking. Giving up smoking is not easy, but the first three-to-four days will be the most difficult. If a person can, they should give up with a friend or family member who also wants to quit.

Here are a few tips to help give up:

- Set a specific date to give up and cut down on the number of cigarettes smoked before that date.

- The support of family and friends will help give up.

- Set a reward for the end of the first day, first week, first month.

- Get rid of everything smoking-related, such as cigarettes, ashtrays and lighters, on the day before giving up.

Step 2 – Stopping

The initial goal is to get through the first day without smoking. If there is a need to put something in the mouth, chew sugarfree gum or something else that is healthy and non-fattening, such as fruit. If needing to do something with one’s hands, find something to fiddle with, such as a pencil, a coin, or a stress relief ball.

Step 3 – Staying stopped

Take it one day at a time. Thinking positively, remaining determined, and rewarding oneself can help. At the beginning, it may help to change normal routine to avoid situations that are normally associated with smoking. Avoiding alcohol for a while may also help. Most importantly, do not give up trying to quit, even if not successful the first time. Most people need several attempts at quitting long-term before they stop smoking completely.

HSE’S brief intervention for smoking cessation (National training programme)

Pharmacological treatments should only be part of a treatment plan for someone giving up smoking. The HSE have a welldefined treatment advice platform for GPs, pharmacists and other clinicians involved in smoking cessation advice called Brief Intervention for Smoking Cessation (National Training Programme). Published in 2012, it advises clinicians in a well-defined manner how to aid the patient to give up smoking.

The Brief Intervention for Smoking Cessation training programme helps clinicians understand tobacco use and includes advice on how clinicians can:

- Utilise brief interventions which involve opportunistic advice, discussion, negotiation, or encouragement.

- Use the ‘Five As’ to help encourage and support patients to give up, ie, Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, Arrange.

- Use motivational interviewing to help the patient through their smoking cessation journey. Motivational interviewing is a counselling technique that was introduced by American psychologists William Miller and Stephen Rollnick in 1983 and is used not just to aid smoking cessation, but in many other areas of mental health support.

- Advise on pharmacological treatment. For this article, I concentrate on the overthe-counter treatment options to aid patients stop smoking. Due to word constraints, I will not discuss e-cigarettes or the two prescription-only smoking cessation drugs (bupropion and varenicline) in detail in this article, but I will return to this subject to discuss them in more detail in Irish Pharmacist in the future.

Pharmacological therapies (OTC or POM) should in no way be seen as standalone treatments to help patients quit. Psychological support and advice from clinicians should be central to the person’s road to becoming smoke-free.

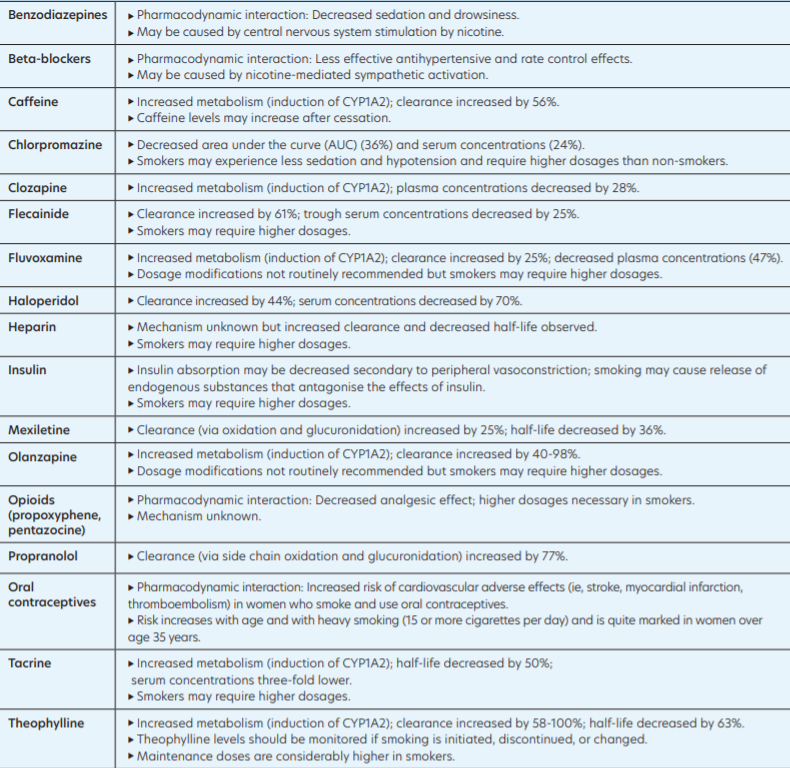

Table 1: Significant tobacco/drug interactions (Reference: Brief Intervention for Smoking Cessation (HSE) 2012)

Drug interactions with smoking

Interactions between tobacco smoke and drugs are often underestimated by patients and clinicians alike. There are pharmacokinetic reasons why tobacco smoke interacts with drugs; namely, tobacco smoke affects the absorption, distribution, metabolism (or elimination) of drugs, thus potentially giving an altered pharmacologic response. Tobacco smoke accelerates the metabolism of certain drugs by inducing hepatic cytochrome P450 en zymes (primarily CYP1A2). It is believed the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in tobacco smoke are responsible for the induction of cytochrome P450 rather than nicotine, meaning that nicotine replacement products do not have the same degree of drug interactions.

The HSE’s Brief Intervention for Smoking Cessation programme (Table 1) documents the main tobacco-drug interactions, with caffeine and fluvoxamine being considered the most clinically significant interactions. Many of the tobacco-drug interactions involve drugs used for mental health disorders. It is well documented that people with mental health disorders have a higher propensity to smoke, so drug interactions can be more of an issue for these patients and need to be considered when patients are giving up smoking, as the concentration of the drug in the bloodstream may be increased as hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes are not being induced by tobacco any longer.

However, as evidenced in Table 1, many of the drugs which tend to have more significant interactions are used less frequently nowadays, ie, typical antipsychotics like haloperidol and chlorpromazine.

Pharmacological treatment options

To help give up, treatment options are available both over the counter in the pharmacy and on prescription.

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT)

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) works by releasing nicotine steadily into the bloodstream at much lower levels than in a cigarette, without the tar, carbon monoxide and other poisonous chemicals found in tobacco smoke. This helps to control the cravings for a cigarette that occur when the body starts to miss the nicotine that smoking provides. The dose depends on the number of cigarettes smoked, intensity, and pattern of habit. NRT increases the rate of smoking cessation compared to placebo by 50-to-70 per cent. NRT is the most common smoking cessation treatment. The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence in the UK (NICE, 2018) recommends a long-acting product (ie, a patch) and a short-acting product, of which there are many varieties; these provide a dose of nicotine to help cravings. Most are absorbed sublingually (ie, vaping, gum, spray, or inhalator). The dose is usually titrated down over a 12-week period, however heavy smokers may need longer.

With a medical card, NRT products available include patches, gum, inhalers, oral sprays and lozenges once prescribed by a GP on the GMS scheme. Bear in mind, the pack sizes available on the GMS for the likes of nicotine gum are bigger dispensing packs rather than the OTC versions. Nicotine replacement products are not available on the Drug Payment Scheme (DPS); despite having PCRS GMS codes. If pregnant or breast-feeding, it is best for the health of mother and baby to stop completely and immediately, without the help of any smoking cessation treatment.

Side-effects of NRT can include:

- Skin irritation from patches.

- Irritation of the nose, throat or eyes when using nasal spray.

- Insomnia and vivid dreams.

- Upset stomach.

- Dizziness.

- Headaches.

Side-effects, if they occur, are generally mild. NRT is not considered as like swapping one addition for another. Smoking is very addictive mainly because it delivers nicotine to the brain very quickly. Nicotine levels in NRT are significantly lower than in tobacco and they deliver nicotine in a more measured way, making them less addictive than smoking.

Types include:

Transdermal patches (which stick to the skin). Available in formulations that release nicotine for either 16 hours or 24 hours. Patches should be applied daily to clean, dry, hairless skin, ie, hip, upper arm, or chest. The 24-hour p atch is advised for patients who need a cigarette as soon as they wake up, ie, Nicquitin CQ, Nicotinell.While the number of weeks advised per strength of patch varies by brand, the general advice is that patients who smoke more than 10 cigarettes a day should start with a 21mg patch for six-to-eight weeks, then taper down to a 14mg patch at weeks six-to-eight, and then a 7mg patch for week nine or 10 if they have no cravings.

Smokers who smoke less than 10 cigarettes a day are advised to start with the 14mg patch daily for four-to-six weeks than the 7mg patch for two-to-four weeks. The time periods between reducing strengths varies between brands (Nicquitin CQ, Nicotinell) and their classification between light smokers (less than 10 or 20 cigarettes daily) varies, so the best advice is to follow the guidance that comes with each specific brand.

Patients who do not need a cigarette first thing in the morning may be advised to use a 16-hour patch, ie, Nicorette. Based on the Nicorette Patch, patients who smoke more than 10 cigarettes a day should start with a

25mg patch daily for eight weeks, then taper down to 15mg daily for weeks nine and 10, and taper down to the 10mg patch daily for weeks 11 and 12 if no cravings. Those who smoke less than 10 cigarettes daily are advised to start the 15mg patch for eight weeks, and then the 10mg patch for four weeks.

The advantages of patches are the patient can put the patch on in the morning and forget about it for the day. The disadvantage is that it is passive, meaning the patient cannot act when craving occurs; this can be particularly difficult for patients who miss ‘smoking gestures’ such as the hand-to-mouth action of having a cigarette; this is where the likes of nicotine inhalators, nicotine gum and e-cigarettes can have an advantage. Combination therapy may be advised for some patients, ie, wearing a patch and using an inhaler or gum for breakthrough cravings, though it should be limited, as if patients are having this level of craving, an alternative option like varenicline (Champix) should perhaps be considered.

Patches are not advised to be used while smoking, though if a patient does smoke while wearing a patch, the rewarding effect of smoking is reduced, as they already have nicotine in the system, so it should reduce the urge to continue smoking. Smoking while wearing a patch risks nicotine overdosing, which can cause dizziness. Patches are often started to aid smoking cessation for patients post-myocardial infarction (MI); this should be under a doctor’s supervision, so should ideally be prescribed by a doctor within four weeks post-MI rather than the patient buying over the counter, where medical supervision is less likely.

Nicotine patches should be used with caution in patients with serious underlying arrhythmias and worsening angina, but in most cases the advantages of giving up smoking outweigh the risks. Nicotine patches are contraindicated during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Fifty per cent of patients have a skin reaction with nicotine

patches but in most cases, this is mild and rotating sites or brands may help. The 24- hour patch can cause vivid dreams or sleep disturbance at night.

Chewing gum that is available with either 2mg or 4mg of nicotine

Brands include Nicorette, Nicotinell and Nicochew gum, which all come in 2mg and 4mg strengths. The 2mg gum is advised for smokers of less than 20 cigarettes daily, and the 4mg gum is advised for smokers of more than 20 cigarettes daily. The patient uses them every one-to-two hours as needed, which depends on nicotine cravings; usually, no more than 15 pieces a day is advised. After three months, gradually reduce using nicotine gum; this can be done by reducing the length of time each piece is chewed or reducing the number of times the patient chews gum daily.

An option when close to getting off the nicotine gum is to cut the gum into smaller pieces. Another option to eventually get of it completely is to swap the nicotine gum for ordinary sugar-free chewing gum, so stopping nicotine gum completely. The advantages of chewing gum are that the patient can use as required and can self-dose. It can be advantageous for patients who miss the ‘gestures of smoking’, as it involves the action of putting something in the mouth and chewing; however, nicotine inhalers are better in these patients. For maximum effect, avoid food and acidic drinks 15 minutes before and while using.

Some patients experience jaw pain or fatigue from frequent chewing and the swallowing of saliva that occurs while chewing nicotine gum can cause nausea, heartburn, and hiccups.

Nicotine inhalers which look like a plastic cigarette and through which nicotine is inhaled

For example, Nicorette 15mg inhaler. The major advantage is that it mimics hand-tomouth action of smoking. Dose is one puff as required and the advised max daily dose is six cartridges. Less is needed if using the inhaler as combination therapy, ie, if using while using a nicotine patch or a prescription smoking cessation therapy like varenicline. Combination therapy of a nicotine inhaler with another therapy like patches is generally not needed,

but it may help some patients who still have some cravings, especially in the first weeks after stopping smoking.

Combination therapy of inhaler and other smoking cessation therapy may be advised for patients who miss

the hand-to-mouth action of cigarettes, but for whom nicotine inhalers are not sufficient on their own, ie, very heavy smokers.

A common misconception of nicotine inhalers is that the patient should inhale deeply; nicotine inhalers are orally absorbed, so there is no need to inhale deeply. Each cartridge lasts for 20-to-40 minutes (around 400 puffs), after that, replace the cartridge. Patients are advised to use the ‘non-smoking hand’ to hold the inhaler to help break the link from the habit of holding a cigarette. A disadvantage is that it is visible in the hand, so is less discreet. For maximum effect, avoid food and acidic drinks 15 minutes before and while using.

Caution is advised for asthmatics due to a very small risk of triggering asthma symptoms, however cigarettes are universally found to have more negative effects for asthmatics than nicotine inhalers. Side-effects are usually mild and can include cough and throat irritation, however these are side-effects often associated with stopping smoking, so these sideeffects may be more to do with this than actual side-effects of the nicotine inhaler.

Lozenges which are placed under the tongue

Brands include Nicquitin CQ, Nicotinell and Nicorette and come in 1mg, 2mg and 4mg lozenges, depending on brands. The 4mg strength is advised for smokers of 20 or more cigarettes daily and who smoke first cigarette within 30 minutes after waking, and the 2mg strength is advised for smokers of 20 or less cigarettes daily and who smoke the first cigarette more than 30 minutes after waking. Dose is one lozenge every one-to-two hours.

Frequency of use varies per brand, but general advice is to use eight-to-12 lozenges per day (no more

than 15) for first six weeks before tapering-off. Each lozenge should last 20-to-30 minutes. If cravings are still experienced after six weeks, the advice is to continue using the lozenges and to keep gradually reducing the number of lozenges used and once down to a use of one-to-two lozenges a day, aim to stop using them completely.

The lozenge is placed (not chewed or swallowed) and allowed to dissolve between cheek and gum. Suck the lozenge until the taste becomes strong then rest between gums and cheek and suck again when the taste fades. Advantages are their ease of use and flexible dosing, and they are available over the counter. For maximum effect, avoid food and acidic drinks 15 minutes before and while using. As with nicotine chewing gum, the swallowing of saliva while using can cause nausea, heartburn, and hiccups.

Nicotine Mouth Spray (only brand is Nicorette Quickmist)

A nicotine mouth spray quickly releases nicotine into the body and is advertised by Nicorette to ease cravings within 30 seconds of use. Dose is one-to-two sprays when needed as cravings occur. Each spray delivers 1mg of nicotine. It can be used in combination with nicotine patches to quell breakthrough urges. To use, point the spray nozzle towards the open mouth, holding as close to the mouth as possible, spraying into the side of the mouth, avoiding the lips. As it is absorbed orally, do not inhale while spraying and for maximum effect do not swallow for a few seconds after spraying.

Maximum dose is four sprays an hour, or 64 sprays a day. Aim to eventually reduce usage down to two-tofour sprays a day, then stop and aim not to use longer than six months, though there is no proof longer use is harmful

NRT not available in Ireland Nicotine Nasal Spray (not launched in Ireland yet)

Nicorette launched a nicotine nasal spray in America (got FDA approval to sell over the counter in 2019) and in the UK. It has not been launched in Ireland, but it is likely to come on the market soon. Each spray delivers 1mg of nicotine, with a maximum of four sprays per hour and maximum of 64 sprays daily.

Micro Tablets

While Nicorette Microtabs are available in the UK and other countries, they are not currently available in Ireland. They work by being placed under the tongue to dissolve and smokers of 20 or more cigarettes daily use one every one or two hours. They are very similar to Nicorette lozenges.

Quick summary of other options

E-cigarettes

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are electronic devices that mimic cigarettes and release nicotine vapour. They allow inhalation of nicotine without the negative effects of tar and carbon monoxide. There are hundreds of different types of devices and juices available. As e-cigarettes are relatively new on the market, and research is ongoing on their benefits and negative effects, the HSE still doesn’t endorse e-cigarettes as an option to help give up cigarettes and recommends NRT (ie, nicotine patches) as the first option.

The World Health Organisation’s opinion is that e-cigarettes should not be recommended as a smoking cessation tool at a population level and warned they can reduce cessation by prolonging or increasing nicotine addiction. Advice from the likes of the Irish Heart Foundation and the Irish Cancer Society to an Oireachtas Committee in November 2021 was that ecigarettes need to face similar sale and advertising restrictions as tobacco products, and they are concerned at the number of teenagers and young people becoming addicted to nicotine through vaping products. Legislation will tighten on the sale and use of e-cigarettes in the coming years but while there are risks from them, they may ultimately share a more official role in aiding smoking cessation as their safety and efficacy continues to be analysed.

Prescription Medication

There are two main treatments available on prescription:

Varenicline (Champix)

Varenicline, whose brand name is Champix. It is available in tablet form. The dose is titrated, meaning the person

smokes for the first eight-to-14 days while taking varenicline before quitting.

The recommended course of Champix is generally 12 weeks. It is a partial agonist that prevents nicotine reaching receptors; it also releases dopamine to help with cravings, meaning it works in two ways — it reduces the enjoyment of a cigarette if a person does smoke while taking it, and it reduces the craving for a cigarette.

Varenicline may not suit everyone and has possible side-effect, including:

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Insomnia and vivid dreams.

- Dry mouth.

- Constipation and diarrhoea.

- Headaches.

- Drowsiness.

- Dizziness.

It is not suitable for:

- Children under 18.

- During pregnancy or breastfeeding.

- People with kidney problems.

- People with epilepsy.

Varenicline has no clinically significant medicine interactions.

Bupropion (Zyban)

Bupropion was originally developed as an antidepressant and the way in which it works in relation to helping stop smoking is not completely understood, but it is thought to work on the brain pathways involved in addiction and withdrawal. It is available in the form of tablets. A course usually lasts eight-to-12 weeks.

Side-effects can include:

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Insomnia.

- Dry mouth.

- Constipation and diarrhoea.

- Dizziness.

- Difficulty concentrating.

It is not suitable for:

- Children under 18.

- During pregnancy or breastfeeding.

- People with epilepsy.

- People with bipolar disorder.

- People with eating disorders.

Varenicline versus bupropion

Bupropion has more contraindications compared to varenicline. Contraindications for bupropion include increased risk of manic episodes in patients with bipolar disorder and a reduced seizure threshold the Harm Reduction Journal in 2009 found varenicline to be more effective than bupropion and NRT for smoking cessation. Varenicline is way more commonly prescribed than bupropion nowadays.

Guidance for prescribers on smoking cessation therapies

It is difficult to get figures on the numbers of NRT and prescription-only smoking cessation drugs (bupropion and varenicline) prescribed in Ireland annually. The Primary Care Reimbursement Service (PCRS) Statistical Analysis of Claims and Payments figures are released annually and over the last 15 years, only twice has NRT been mentioned in the figures.

In 2014, NRT products were prescribed 137,192 times under the PCRS’s general medical card scheme (GMS) at a cost to the State of €4,931,977, making it 35th of the top 100 products by ingredient cost. In 2017, NRT products were prescribed 140,003 times under the PCRS’s general medical card scheme (GMS) at a cost to the State of €5,303,121, making it 18th of the top 100 products by ingredient cost that year. There is no recent data to indicate the breakdown of NRT by product on the GMS.

NRT became reimbursable on the GMS (ie, free to medical card patients) from 2001 and based on figures soon after they were allowed (2002), nicotine patch therapy accounted for 82.8 per cent of all NRT dispensed in 2002 on the GMS scheme and based on dispensing trends seen in pharmacies, patches are still likely to account for over 80 per cent of NRT prescriptions on the GMS.

Prescribing advice taken from NICE in the UK (Table 2) and embraced by the HSE and aims to reduce wastage in the prescribing of NRT products. It advises that smaller amounts of NRT (two weeks) are prescribed initially, with more only be prescribed when it is seen that the patient has shown a continued commitment after the initial two-week period to continuing to give up.

Support from the HSE

Contact the Quit Team for free support at Freephone: 1800 201 203, free text: QUIT to 50100, Email:support@quit.ie Twitter: @HSEQuitTeam

References: Available upon request

Disclaimer: Brands mentioned in this article are meant as examples only and not meant as preference to other brands.

Contributor Information

Written and researched by Eamonn Brady (MPSI), owner of Whelehans Pharmacies in Mullingar Tel 04493 34591 (Pearse St) or 04493 10266 (Clonmore). www.whelehans.inet. Eamonn specialises in the supply of medicines and training needs of nursing homes throughout Ireland. Email ebrady@whelehans.ie