Dr Donna Cosgrove PhD MPSI looks at the current state of play with High Tech medicines in Ireland

As a class, High Tech products include expensive medicines that have been produced by biotechnological means (ie, the use of living organisms to create or modify products), new drugs with significant new therapeutic uses, or drugs that require prescribing by a consultant in a hospital setting.1 Immunosuppressants (to prevent transplant organ rejection), cancer treatments, and medicines used in assisted reproduction are just a few examples included in the collection of medications vreimbursed under the High Tech Drug Scheme. The HSE pays drug companies directly for High Tech medicines to facilitate the dispensing of High Tech Drugs (HTD) through com- munity pharmacies, in an arrangement that began in 1996. The persistent and significant rate of growth of the HTD scheme has raised concerns around funding sustainability.

THE COST OF MEDICINES TO THE IRISH STATE

Most of Ireland’s pharmaceutical expenditure is via the HSE Primary Care Reimbursement Service (PCRS), although hospitals and other health services also contribute to this. In a recent review of HTD expenditure in Ireland,2 the authors note that the complexity, and the spread across several areas, makes it challenging to track the total pharmaceutical spend accurately. However, estimates show that the cost of pharmaceuticals to the Irish State has grown from €1.3 billion in 2012, to €2.3 billion in 2020.

The most obvious contributor to this is HTD, the annual cost of which has increased from €380 million in 2012, to just under €1 billion in 2021. This is an average increase of 11 per cent, or €63 million, each year. There are a number of reasons for this increase:

- Growth in number of patients using HTD v— from 57,000 in 2012, to 89,000 in 2019 (a 6.9 per cent increase per year).

- New, higher-cost medicines.

- HTD, as described by the name, includes medicines that are more technologically advanced, with many remaining under patent.

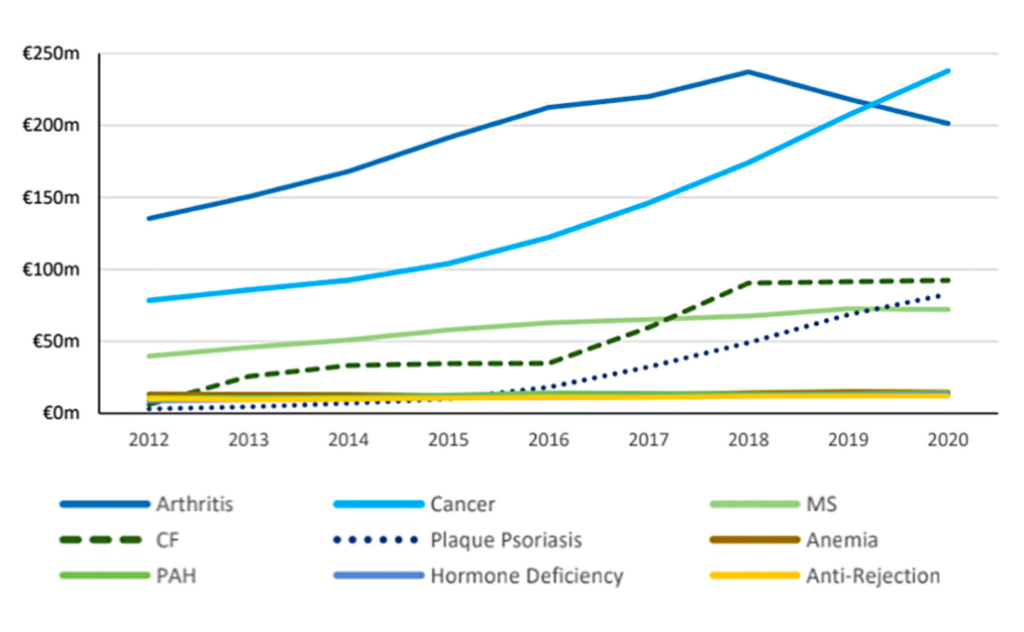

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and cancer are the primary drivers of the HTD cost. This is due to both large patient volumes and larger annual treatment costs (approximately €12,700 and €13,500 per patient per annum, respectively) compared to other treatments. The average annual cost of treating RA is decreasing due to the use of biosimilars, but the cost of cancer treatments continues to rise.

A Framework Agreement on the Price and Supply of Medicines (the FASPM, also known as the ‘IPHA Agreement’), signed between the State and industry in 2016, has reduced the pharmaceutical drug bill by over €750 million since it was established. This agreement included multiple elements to promote cost- effectiveness, including that unit prices do not increase over the term of the arrangement; and when a generic medicine is launched, the originator medicine list price will reduce by 50 per cent (20 per cent in the case of biosimilars). A general rebate of the HTD price is also repaid to the HSE.

The research-based pharmaceutical industry has agreed to staged increases in rebates to the State on sales of on- patent and off-patent unique medicines, rising from an initial 5.5 per cent from 2021, to reach 9 per cent in October 2024. The industry will deliver about €89 million in rebates in that period.

BIOSIMILARS

In Ireland, 15 per cent of the spend on pharmaceuticals is on generic medications. This is low when compared to 24 per cent in the OECD overall, and 36 per cent in the UK. Just over 20 per cent of the HTD expenditure is on biosimilars or generics, lower than average in the OECD and the UK. Although this is a small proportion, it is still a significant increase from 2012, when it was only about 5 per cent.2 The authors of the HTD spending review suggest that, as a first step, the publication of a ‘biosimilar strategy’, backed with appropriate targets, performance indicators and milestones, should be established, as has been done in other countries.

The top drugs by gross expenditure in Ireland where biosimilar or generic alternatives exist are:

1. Adalimumab.

2. Etanercept.

3. Somatropin.

4. Teriparatide.

5. Tobramycin.

6. Imatinib.

7. Leuprorelin.

8. Triptorelin.

9. Follitropin alfa.

10. Sildenafil.

11. Tadalafil.

For many HTDs, the entire expenditure is on the originator, likely due to a lack

of alternatives either in the Irish market or generally. Where biosimilars are available, they are on average 77 per cent of the cost of their branded alternative (based on 2020 prices).

EVALUATION AND REIMBURSEMENT DECISIONS

All medicines undergo a scientific evaluation with the European Medicines Agency to obtain a market authorisation for the EU. In Ireland, the medicine must also be approved by the HPRA prior to use here. Once market authorisation is granted, the pharmaceutical company applies for the medicine to be reimbursed. The criteria for this decision are set out in the Health (Pricing and Supply of Medical Goods) Act 2013, and include factors such as patient safety, cost-effectiveness, and appropriate use of pharmaceutical items and financial resources.

There are multiple stages to this decision process, with the initial stage involving a review by the National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics (NCPE), which analyses the efficacy of the drug vs the cost given by the manufacturing company. The NCPE uses this information to decide whether or not the medicine represents value for money in the Irish health system, and if it should be eligible for reimbursement by the HSE. After an NCPE recommendation is made, the decision is then evaluated by HSE officials.2

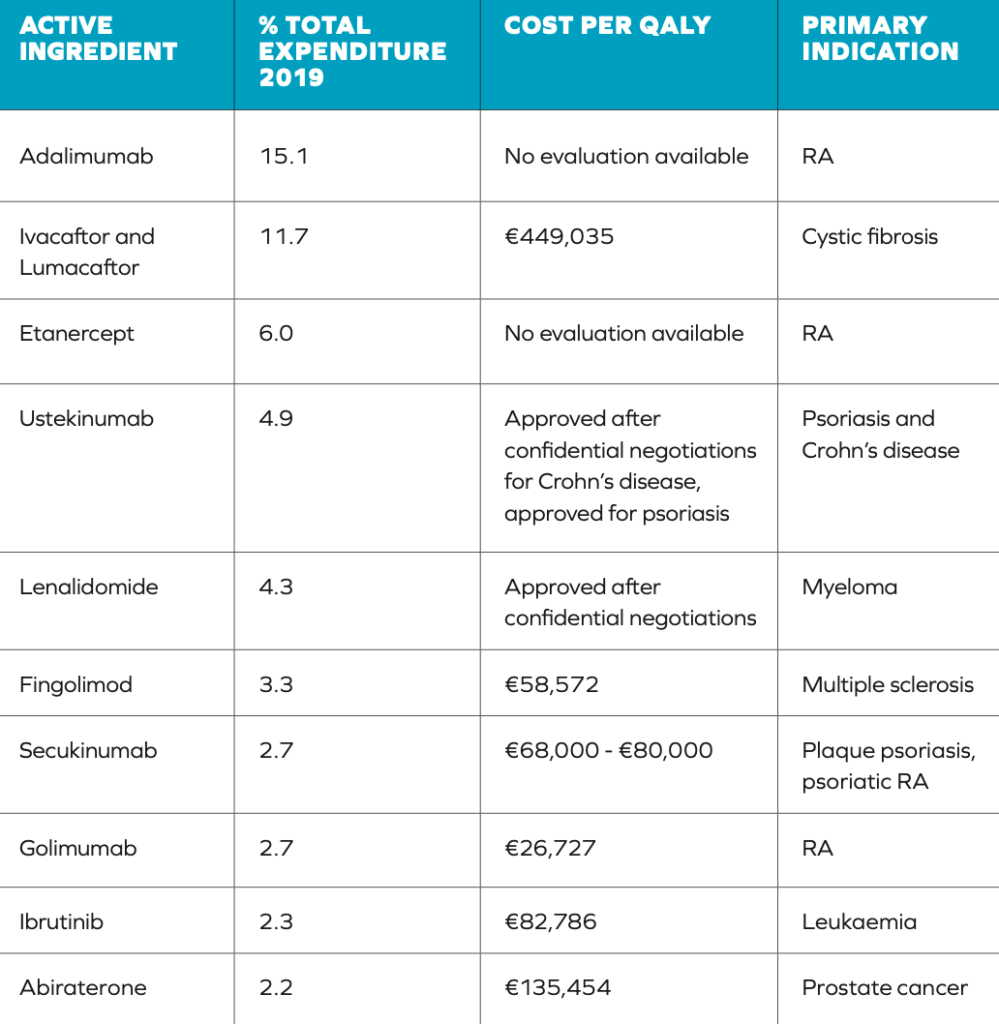

Many countries perform a Health Technology Assessment (HTA) to determine what medicines or interventions should be funded through the State. This is a multidisciplinary process that summarises information about the medical, social, economic and ethical issues related to the use of a health technology in a systematic, transparent, unbiased, robust manner. This is done to help formulate health policies that are safe, effective, patient- focused, and the best value.4 In Ireland, HTAs are carried out by the NCPE in collaboration with the HSE. Based on drug efficacy and cost, the NCPE establishes a standardised measure of health improvement offered by a medicine in terms of Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY). Use of the QALY as an outcome measure has two main advantages: It incorporates a measure of value for different health states; and it facilitates comparisons between different treatments. This increases its usefulness to decision-makers who are in charge of the allocation of the State’s finite resources. In the past, the NCPE has recommended reimbursement for drugs that offer benefits of one QALY per €45,000 spend or less.2

There have been criticisms of both the established QALY threshold and how it is used in making decisions. There is a question regarding how this threshold was set, which is higher than the threshold applied in other countries such as the UK (the cost per QALY threshold by NICE for England and Wales is between £20,000 and £30,000).5 A more significant issue, however, is the frequency with which this defined threshold is exceeded in reimbursement decisions (Table 1), highlighted by the authors of the HTD spending review.2 Table 1 illustrates some discrepancies in the application of the €45,000 threshold. Out of the 10 medicines included, five have costs per QALY in excess of the threshold. The final cost effectiveness evaluation of other drugs is unclear due to them being subject to commercially confidential pricing.

There may be cases where drugs are ultimately approved, despite poor cost effectiveness, because of political sensitivities surrounding the drug approvals for some medical conditions. Many HTD medicines that target illnesses with a huge negative impact on patients’ health and quality of life can offer proven patient benefits, in some cases providing treatment where there are limited alternatives. Decisions on whether to reimburse these medications are tricky, and may be subject to significant political pressure.6 These innovative HTDs are expensive, and these high prices are posing a difficult challenge for balancing the desire to maximise the accessibility of treatment under the High Tech Scheme, while ensuring affordability for the State.

Many HTD medicines that target illnesses with a huge negative impact on patients’ health and quality of life can offer proven patient benefits

PRICING AGREEMENTS

In many cases, there are complicated pricing arrangements between governments and the pharmaceutical industry which are subject to non- disclosure agreements. This can prevent comparisons between countries of the prices of pharmaceuticals supplied.

This provides an advantage to the pharmaceutical industry, as it reduces states’ ability to evaluate comparative value for money across other areas. In Ireland, the IPHA agreement means that medication unit prices may not increase for the duration of the agreement. As a result, the manufacturer typically sets a higher initial price for new medicines so that an adequate return is made vs the investment.

There has been a gradual shift in many European countries over the last few years to drive initiatives to introduce more information sharing and collaboration about pharmaceutical policy and procurement. Since 2018, Ireland is one of five members of the Beneluxa initiative (the other members are Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg and Austria), an initiative that encourages: ?Information exchange on medicine policies.

- Co-operation in HTA.

- Increased transparency in pharmaceutical pricing between countries.7

The European Commission Pharmaceutical Strategy8 endorses greater information sharing for pharmaceutical policy, including for public procurement and the production cost of pharmaceuticals. It outlines

the potential of joint procurement in pharmaceuticals between EU states and offers a forum for improving dialogue on issues such as R&D transparency, pharmaceutical affordability, and HTA.

REFERENCES

1. European Medicines Agency (2023). Biotechnology. Available https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/ glossary/biotechnology.

2. Prior S, Scott R, Hennessy M, & Walker E (2021). Spending Review 2021 – Review of High-Tech Drug Expenditure. Departments of Public Expenditure and Reform, and Health. Available https://assets.gov. ie/193851/9490e808-1774-440d- 843a-28c3a9dc195c.pdf.

3. Irish Pharmaceutical Healthcare Association (2021). New medicines supply agreement to improve patients’ access to innovative new treatments. Available https://www.ipha.ie/ new-medicines-supply-agreement- to-improve-patients-access-to- innovative-new-treatments/.

4. Health Information and Quality Authority (2020). Guidelines for the Economic Evaluation of Health Technologies in Ireland. Available https://www.hiqa.ie/sites/default/ files/2020-09/HTA-Economic- Guidelines-2020.pdf.

5. Office for Health Improvement and Disparities UK (2020). Guidance Cost utility analysis: Health economic studies. Available https://www.gov.uk/ guidance/cost-utility-analysis-health- economic-studies#:~:text=It%20 allows%20a%20quick%20 assessment,%C2%A320%2C000%20 and%20%C2%A330%2C000.

6. O’Mahony JF (2021). Revision of Ireland’s Cost-Effectiveness Threshold: New State-Industry

Drug Pricing Deal Should Adequately Reflect Opportunity Costs. PharmacoEconomics- Open, 5(3), 339-348.

7. Beneluxa Initiative on Pharmaceutical Policy, (2022). Beneluxa Initiative. Available https://beneluxa.org/collaboration.

8. The European Commission (2020). Pharmaceutical Strategy for Europe. Available https://health.ec.europa. eu/system/files/2021-02/pharma- strategy_report_en_0.pdf.