Asthma is a long-term condition that can cause a cough, wheezing and breathlessness and the severity of the symptoms varies from person-to-person

Causes

With asthma, the airways become over-sensitive and react to stimuli that would normally not cause a problem, such as cold air or dust. Muscles around the wall of the airway tighten up, making it narrow and difficult for air to flow in and out. The lining of the airways swells, and sticky mucus is produced. This makes it difficult for air to move in and out. Tightening of muscle around the airways can happen quickly and is the most common cause of mild asthma. The tightening of muscle can be relieved with a reliever inhaler. However, the swelling and build-up of mucus happen more slowly and need a different treatment. This takes longer to clear up and is a serious problem in moderate-to-severe asthma.

Symptoms

- Difficulty in breathing/shortness of breath.

- A tight feeling in the chest.

- Wheezing (a whistling noise in the chest).

- Coughing, particularly at night.

- Hoarseness.

These symptoms may occur in episodes, perhaps brought on by colds or chest infections, exercise, change of temperature, dust, or other irritants in the air, or by an allergy ie, pollen or animals. Episodes at night are common, often affecting sleep.

Common triggers

Anything that irritates the airways and brings on the symptoms of asthma is called a trigger. Common triggers include house dust mites, animal fur, pollen, tobacco smoke, exercise, cold air and chest infections. Other triggers which are less common include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen and diclofenac, emotional factors such as stress, sulphites in some foods and drinks (found in certain wines and used as a preservative in some foods such as fruit juices and jam), mould or damp in houses, and food allergies, ie, nut allergy.

Many asthmatics find their symptoms worsen during hay fever season. This is due to the fact that hay fever causes the airways that are already inflamed to swell up even more, thus exacerbating breathlessness. The same substances that are triggers for hay fever (allergic rhinitis), such as pollen, dust mites and pet dander, are also triggers for asthma, so the two conditions are intrinsically linked. As well as hay fever, many asthmatics also suffer from other allergic conditions, such as eczema and hives.

Severe Asthma

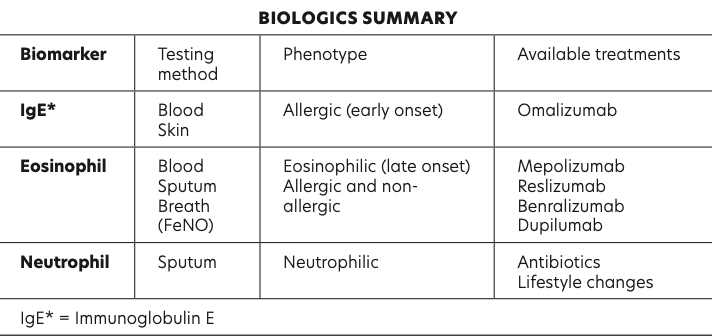

Around 4 per cent of asthma patients have severe asthma that does not improve with traditional asthma medication. The two main types of severe asthma are type 2 inflammation and non-type 2 inflammation. These categories are based on a patient’s response to treatment.

Type-2 inflammation includes allergic

(IgE-mediated) asthma and eosinophilic asthma. Non-type-2 inflammation

includes non-eosinophilic asthma.

Two sub-types of severe asthma

1. Type 2 inflammation (Also known as T2 High Inflammation)

- Allergic asthma

This is caused by exposure to allergens such as pollen, pet dander and moulds. Patients diagnosed with allergic asthma nearly always have a diagnosis of hay fever. Exposure to allergens triggers the immune system to produce immunoglobulin E (IgE), an antibody that attaches to cells, causing the release of chemicals, causing an allergic reaction. Symptoms include sneezing, itchy/watery eyes, airway sensitivity and anaphylaxis.

- Eosinophilic asthma

Approximately 40 per cent of people with severe asthma have eosinophilic asthma. This is asthma caused by high levels of eosinophils (type of white blood cell). High levels of eosinophils cause the airways to become inflamed, leading to severe asthma. It can be diagnosed with a blood test. Eosinophilic asthma is often characterised by other symptoms of inflammation, such as eczema, sinusitis, and nasal polyps because eosinophilic cells cause inflammation not only in the respiratory system, but anywhere in the body. Biologic drugs may be needed to control eosinophilic asthma.

2. Non-type 2 inflammation (Also known as T2 Low Inflammation)

- Non-eosinophilic asthma

Patients with this type of severe asthma have few to no eosinophils in test results.

Neutrophilic asthma is a type of non-eosinophilic asthma. Neutrophils are the most common white blood cell in the body that help fight infections. Having too many neutrophils can cause non-type-2 inflammation in the airways, leading to severe asthma symptoms. This type of asthma does not respond well to inhaled corticosteroids, as using them can cause an increase in neutrophils. Neutrophilic asthma also does not respond to biologics. Neutrophilic asthma is associated with chronic bacterial or viral infections, smoking, obesity, and airway smooth muscle abnormalities.

Diagnosis

The following questions can help ascertain

if asthma is the problem.

- Is there a family history of asthma?

- Are symptoms frequent and do they

affect quality of life?

- Has there been an attack or recurrent attacks of wheezing?

- Is there a regular night-time cough?

- Does exercise trigger wheezing

or coughing?

- Is there wheezing, chest tightness, or cough after exposure to airborne allergens or pollutants?

- Does the patient suffer from constant chest infections?

- Do chest infections take a long time to clear up?

Are symptoms improved by when using a reliever inhaler?

Answering ‘yes’ to a number of these questions indicates asthma.

The following tests are often done to confirm the diagnosis of asthma:

1. Spirometry is a simple breathing test that gives measurements of lung function. A spirometer is the device that is used to make the measurements. It is common to measure lung function with a spirometer before and after a dose of reliever to see if lung function has improved

2. Peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) is a breathing test. It uses a simple hand-held device called a peak flow meter, which a patient blows into to measure lung function. The PEFR test is only suitable for children over five years of age.

3. An exercise test to check if exercise worsens asthma symptoms.

When to get immediate help

The following are signs of a severe

asthma attack:

- The reliever inhaler does not help symptoms at all.

- The symptoms of wheezing, coughing, tight chest are severe and constant.

- Too breathless to speak.

- Pulse is racing.

- Feeling agitated or restless.

- Lips or fingernails look blue.

Treatment

Non-Pharmacological Management

Asthmatics should be advised strongly not to smoke and to lose weight. Allergen avoidance measures may be helpful but the benefit of avoiding allergens such as dust mites or animal fur has not been proven in studies. There is insufficient or no evidence of the clinical benefit of complementary therapy for asthma, such as Chinese medicine, acupuncture, breathing exercises and homeopathy.

General Medication Guidance

There is no cure for asthma. Symptoms can come and go throughout the person’s life. Treatment can help control the condition. Treatment is based on relief of symptoms and preventing future symptoms and attacks from developing. Successful prevention can be achieved through a combination of medicines, lifestyle changes and identification and avoiding asthma triggers.

Short-acting beta 2-agonist (SABA)

A short-acting beta 2-agonist (SABA) opens the airways and is best known to patients as a reliever inhaler. These work quickly to relieve asthma. They work by relaxing the muscles surrounding the narrowed airways. Examples of beta 2-agonists include salbutamol and terbutaline. They are usually blue in colour. They are generally safe medicines with few side-effects, unless they are overused. It is important for every asthmatic to have a beta-2 agonist inhaler. If an asthmatic needs to use their beta agonist inhaler too regularly (three or more times per week), they should have their therapy reviewed. The main side-effects include a mild shaking of the hands, headache, and muscle cramps. These usually only occur with high doses of relievers and usually only last for a few minutes.

Excessive use of short-acting relievers

has been associated with asthma deaths. This is not the fault of the reliever medication, but down to the fact that the patient failed to get treatment for their worsening asthma symptoms.

Corticosteroid Inhalers

Corticosteroid inhalers are slower-acting inhalers that reduce inflammation in the airways and prevent asthma attacks occurring. The corticosteroid inhaler must be used daily for some time before full benefit is achieved. Examples of corticosteroids used in inhalers include beclomethasone, budesonide, and fluticasone. Corticosteroid inhalers are often brown, red, or orange. The dose of inhaler will be increased gradually until symptoms ease. For example, a patient may start on a beclomethasone 100mcg inhaler and may be put on a beclomethasone 250mcg inhaler if there is not enough improvement in symptoms.

Preventer treatment is normally recommended if the patient:

- Has asthma symptoms more than

twice a week.

- Wakes up once a week due to asthma symptoms.

- Must use a reliever inhaler more than twice a week.

Regular inhaled corticosteroids have been shown to reduce symptoms, exacerbations, hospital readmissions and asthma deaths.

Corticosteroid Dosage

The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) pathways guidance for inhaled corticosteroid use as updated in March 2021 is as follows:

For adults aged 17 and over:

u 400 micrograms (or less) of budesonide or equivalent is defined as low dose.

u 400 micrograms to 800 micrograms budesonide or equivalent is defined as moderate dose.

u Greater than 800 micrograms budesonide or equivalent is defined as high dose.

For children aged 16 and under:

u 200 micrograms (or less) of budesonide or equivalent is defined as a low paediatric dose.

u 200 micrograms to 400 micrograms budesonide or equivalent is defined as a moderate paediatric dose.

u Greater than 400 micrograms budesonide or equivalent is defined as a high a high paediatric dose.

The dose of corticosteroid inhaler maintenance therapy should be adjusted over time, aiming for the lowest dose that gives effective asthma control.

The majority of patients require a dose of less than 400mcg per day to achieve maximum or near-maximum benefit. Side-effects are minimal at this dose. Smoking can reduce the effects of preventer inhalers. Corticosteroids are very safe at usual doses, although they can cause some side-effects at high doses, especially over long-term use. The main side-effect of corticosteroid inhalers is a fungal infection (oral candidiasis) of the mouth or throat.

This can be prevented by rinsing the mouth with water after inhaling a dose. The patient may also develop a hoarse voice. Using a spacer can help prevent these side-effects.

Long-acting reliever inhalers (LABA)

If short-acting beta 2-agonist inhalers and corticosteroid inhalers are not providing enough symptom relief, a long-acting reliever (long-acting beta 2-agonist or LABA) may be tried. Inhalers combining an inhaled steroid and a long-acting bronchodilator (combination inhaler) are more commonly prescribed than LABAs on their own. LABAs work in the same way as short-acting relievers, but they take longer to work and can last up to 12 hours. A salmeterol inhaler is an example of a long-acting reliever inhaler. Long-acting relievers may cause similar side-effects to short-acting relievers, including a mild shaking of the hands, headache, and muscle cramps. Long-acting reliever inhalers should only be used in combination with a preventer inhaler. Studies have shown that using a LABA on its own (without a combination corticosteroid) can increase asthma attacks and can even increase the risk of death from asthma, though increased risk of death is small. In November 2005, the Food and Drug Administration in the United States issued an alert indicating potential increased risk of worsening symptoms and sometimes death associated with the use LABAs on their own.

LABA/Corticosteroid inhaler Combinations

Examples of combination inhalers containing long-acting beta 2-agonist and steroids include Seretide and Symbicort. Combination inhalers containing beta 2-agonists and corticosteroids can be very effective in attaining asthma control. They have been shown to have better outcomes compared to leukotriene receptor antagonists such as montelukast. Both treatment options led to improved asthma control; however, compared to leukotriene receptor antagonists, the addition of long-acting beta 2-agonist to inhaled corticosteroids is associated with significantly improved lung function, symptom-free days, less need for short-term beta 2-agonists, fewer night awakenings, and better quality of life. However, the magnitude of some of these differences is small.

Long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs)

Long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) have been long recognised in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). In asthma, muscarinic antagonists (both short- and long-acting) were traditionally considered less effective than ?2-agonists; only relatively recently have studies been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of LAMAs, as add-on to either inhaled corticosteroid monotherapy or inhaled corticosteroid/LABA combinations. These studies led the first approval of the LAMA tiotropium (in the form of Spiriva Respimat) as an add-on therapy in patients with poorly-controlled asthma. Spiriva Respimat was approved for uncontrolled asthma in adults in 2014 and its licence was extended to approval for uncontrolled asthma in children aged over six in 2018. LAMAs work by opening narrowed airways for at least 24 hours.

Subsequently, a number of single-inhaler corticosteroid/LABA/LAMA triple therapies have been approved or are in clinical development for the management of asthma. There is now substantial evidence of the efficacy and safety of LAMAs in asthma that is uncontrolled despite treatment with an inhaled corticosteroid/LABA combination.

MART Regimen

MART regimen, which stands for ‘Maintenance And Reliever Therapy’, is a form of combined corticosteroid and LABA treatment using a single inhaler, containing both corticosteroids and a fast-acting LABA. It is used for both daily maintenance therapy and the relief of symptoms as required. It is only suitable for corticosteroids and LABA combinations where the LABA has a fast-acting component, for example a formoterol and budesonide inhaler, ie, Symbicort. It is important that the patient can understand and comply with the MART regimen.

Occasional use of oral corticosteroids

Most patients only need to take a course of oral corticosteroids for one or two weeks. Once the asthma symptoms are under control, the dose can be reduced slowly over a few days. Oral corticosteroids can cause side-effects if they are taken for more than three months or if they are taken frequently (three or four courses of corticosteroids a year).

Side-effects can include:

- Weight gain.

- Thinning of the skin.

- Osteoporosis.

- Hypertension.

- Diabetes.

- Cataracts and glaucoma.

- Easy bruising.

- Muscle weakness.

To minimise the risk of taking oral corticosteroids:

- Eat a healthy, balanced diet with plenty

of calcium.

- Maintain a healthy body weight.

- Stop smoking.

- Only drink alcohol in moderation.

- Do regular exercise.

Other Preventer medication

If treatment of asthma is still not successful, additional preventer medicines can be tried prior to considering biologics. Possible alternatives include:

Leukotriene receptor antagonists (montelukast): Act by blocking part of the chemical reaction involved in inflammation of the airways. Montelukast is particularly beneficial for two types of asthma:

A. Asthma predominantly induced by exercise.

B. Asthma associated with allergic rhinitis.

Other types of asthma where montelukast has shown efficacy include asthma in obese patients, asthma in smokers, aspirin-induced asthma, and viral-induced wheezing episodes. The fact that leukotriene receptor agonists help allergic rhinitis symptoms (ie, asthma) is a positive. Leukotriene receptor agonists do not usually cause side-effects, although there have been reports of stomach upsets, feeling thirsty and headache.

Theophylline: Helps widen the airways by relaxing the muscles around them. Theophylline is known to cause potential side-effects, including headaches, nausea, insomnia, vomiting, irritability, and stomach upsets. These can usually be avoided by adjusting the dose. It has a narrow therapeutic index, meaning the balance between suboptimal dosage and overdosage is difficult to manage. Despite theophylline being around for over 80 years, it still offers an inexpensive option as an add-on therapy where the likes of inhaled corticosteroids/LABAs/LAMAs/ leukotriene receptor antagonists are not controlling symptoms sufficiently.

Macrolides, ie, azithromycin: Oral macrolide therapy has been shown to improve quality of life in people with asthma. Treatment with macrolides results in an improvement in asthma symptoms in some patients, although

this is small in magnitude and is not applicable to all patients with asthma.

Studies with macrolide antibiotics in asthma in short antimicrobial courses and in longer, lower-dose regimens (ie, azithromycin 250mg or 500mg three times a week) suggest a possible non-antimicrobial mode of action, possibly as a steroid-sparing agent. British Thoracic Society guidance on the use of long-term macrolides in adults with respiratory disease published in 2019 summarised the findings as “there is insufficient evidence to make any recommendation on the impact of oral macrolide therapy on mortality, exercise capacity, disease progression or sputum characteristics in people with asthma”. While macrolides do have a slightly more proven benefit at reducing symptoms of COPD, further research, over a longer period, is needed to investigate the role of long-term macrolide therapy in reducing exacerbations of asthma. Azithromycin can cause QTc prolongation, liver function issues and hearing loss, so patients must be closely monitored. Referral to a respiratory specialist is advised prior to initiation of macrolide therapy for asthma, especially considering its use in asthma is an unlicensed indication.

When can therapy be reduced?

Once control is achieved and sustained, gradual stepping down of therapy is recommended. Good control is reflected by the absence of night-time symptoms, no symptoms on exercise, and the use of relievers less than three times a week. Patients should be maintained on the lowest effective dose of inhaled steroids, with reductions of 25-to-50 per cent being considered every three months.

Biologics for difficult and severe Asthma

Biologics are a new class of drugs

called monoclonal antibodies that are licenced for severe asthma. They reduce the inflammation in the respiratory

tract. Only respiratory specialists can prescribe biologics.

Most biologics are given by subcutaneous injection once or twice a month. All biologics are an add-on option and do not replace existing reliever and preventer medication, but patients should eventually be able to reduce the dosage of existing therapies such as inhaled corticosteroids. Biologics are available to target the two subtypes of type-2 severe asthma, ie, allergic (IgE-mediated) asthma and eosinophilic asthma.

Biologic therapy drugs for severe asthma include:

- Omalizumab (Xolair).

- Mepolizumab (Nucala).

- Reslizumab (Cinqair).

- Benralizumab (Fasenra).

- Dupilumab (Dupixent).

Of the five biologics listed above, Omalizumab is an anti-IgE agent, and the other four biologics are anti-eosinophilic agents.

Biologics are expensive (average cost is €15,000 per year), require frequent monitoring and are limited to specific clinical phenotypes, meaning use is limited to strict protocols. The benefits of reduced exacerbations of asthma, reduced steroid burden, and the potential for decreased hospitalisations means health authorities are increasingly funding their use. More research is required to better identify appropriate patients for use of biologics, including better use of biomarkers and phenotypes in the management of acute asthma and the selection of biologics for the right patients at the appropriate time.

In clinical trials, all five biologics reduced annualised exacerbation rates by at least 50 per cent and they all improved asthma symptom scores, lung function and quality of life, and allowed reductions in maintenance oral corticosteroids while maintaining a favourable safety profile.

Side-effects

Biologics used for asthma have a good safety profile. The most serious potential side-effect of biologic therapies is an allergic or allergic-like reaction, with some patients very rarely experiencing severe anaphylaxis. These reactions are rare but can be serious. Symptoms of an allergic reaction can include breathing difficulties, faintness/dizziness, rash, swelling, and itching. Allergic reactions mostly occur immediately after the injection but in some cases, symptoms may not occur for a few days after the injection.

Less-severe but more common side-effects of biologics include:

- Headache.

- Pain, redness, itching, and/or a burning sensation at the injection site.

- Increased risk of infections such as colds, flu, and urinary tract infections.

How long should biologics be used?

There are currently no set guidelines on how long a biologic should be used for severe asthma. Guidelines recommend trialling a biologic for a minimum of four months to determine if it improves severe asthma symptoms. As part of their funding by health authorities like the HSE and NHS, consultants are given specific guidelines of how often to review. The consultant will decide if the biologic is to continue based on response.

European guidelines on biologic use

Treatment guidelines were produced by the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) and published in the journal Allergy in 2020.

GRADE approach to recommending biologics

Before I discuss the EAACI guidance for biologics in asthma, I will explain the use of the GRADE approach and meaning of the terms ‘strong recommendation’ and ‘conditional recommendation’ when outlining the effectiveness of therapies. GRADE offers a transparent and structured process to develop and present evidence summaries and for carrying out the steps involved in developing recommendations.

- A ‘strong recommendation’ is where the reviewers are confident the desirable effects of taking a medication outweigh the undesirable effects.

- A ‘conditional recommendation’ is one where the reviewers conclude the desirable effects of taking a medication ‘probably’ outweigh the undesirable effects, but the reviewers are not confident about these trade-offs. Reasons for not being confident may include:

- Absence of high-quality evidence.

- Presence of imprecise estimates of benefits or harms.

- Uncertainty or variation in how different individuals value the outcomes.

- Minimal benefits.

- The benefits may not be worth the costs (ie, high cost of the drug).

EAACI Biologic Therapies recommendations

Omalizumab

Omalizumab is indicated for adults, adolescents, and children (6 to <12 years of age) and the licence states that omalizumab should only be considered for patients with severe confirmed IgE (immunoglobulin E) mediated asthma,

ie, allergic asthma.

Adults: The EAACI suggest that adults with both allergic and non-allergic severe uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma may benefit from the addition of omalizumab.

Omalizumab is ‘strongly recommended’ to reduce exacerbations, and ‘conditionally recommended’ as safe and effective for the improvement of lung function and quality of life and the reduction in dosage of current traditional asthma treatment. In addition, a ‘conditional recommendation’ is given for the use of omalizumab to lower the use of inhaled corticosteroids.

Children 6 to 12: Omalizumab may be added to existing therapy for children aged six to 11 years with moderate-to-severe allergic asthma not controlled by background medications, with a ‘conditional recommendation’ for its use for the reduction of symptom exacerbations and inhaled corticosteroids and the improvement of lung function and quality of life.

Mepolizumab

Mepolizumab is an IL-5 inhibitor licenced as add-on therapy in adults and children over six with severe uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma. Mepolizumab has ‘strong recommendations’ to limit exacerbations and taper oral corticosteroids, and ‘conditional recommendations’ regarding safety and improvement in lung function, disease control and quality of life. Mepolizumab has ‘conditional recommendations’ as an add-on to treat adolescents aged 12-to-17 years who have severe uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma.

Reslizumab

Reslizumab is ‘strongly recommended’ as add-on treatment for adults with severe uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma who are taking controller medications as a way to lower symptom exacerbations. It is also ‘conditionally recommended’ as safe and effective for the improvement of lung function, disease control, and quality of life.

Benralizumab

Licenced as add-on therapy for adults with severe eosinophilic uncontrolled asthma. Benralizumab is an IL-5 inhibitor. It is strongly recommended as add-on therapy to reduce severe exacerbations and taper oral corticosteroids when the blood eosinophil count is >150/µL. Benralizumab is ‘conditionally recommended’ as safe and effective for the improvement of lung function, disease control, and quality of life. The EAACI ‘conditionally recommended’ benralizumab as add-on treatment for patients aged 12-to-17 years with severe uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma and adults with uncontrolled severe allergic asthma.

Dupilumab

It is approved for severe asthma with type 2 inflammation characterised by raised blood eosinophils and/or raised fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO); it is approved as add-on therapy for adults and adolescents aged 12-to-17 years.

It is licenced in Ireland to treat moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (atopic eczema) and earlier in 2021, the HSE Drug’s Group approved reimbursement of dupilumab for this atopic dermatitis, meaning it is available under the High Tech scheme since 1 April 2021, for atopic dermatitis. In early 2021, the indication of severe asthma was added to its licencing in Ireland, allowing it to be prescribed for this indication. However, like the other biologics, it is not reimbursable under the HSE community drug schemes so it not universally available to patients due to cost.

Dupilumab blocks two interleukin proteins called (IL-4 and IL-13), which differentiates it from the other biologic therapies; it has shown very favourable results in asthma trials. The EAACI ‘strongly recommends’ it as add-on therapy to reduce symptom exacerbation and improve lung function. For adults over 17, Dupilumab is ‘conditionally recommended’ as safe and effective for the improvement of asthma control and quality of life and the reduction of the need for other medications. Dupilumab is ‘conditionally recommended’ as add-on therapy for children and adults over 12 with severe uncontrolled allergic asthma to increase lung function and control disease, while limiting severe exacerbations.

When dupilumab is used as an add-on to treat severe uncontrolled type-2 asthma in over-12s, it is ‘strongly recommended’ to reduce exacerbations, increase lung function, and taper oral corticosteroids, and ‘conditionally recommended’ to improve quality of life and asthma control and the reduction of the need for other medications.

Availability of Biologics for Asthma in Ireland

Biologics in Ireland are not approved for use under the community drug schemes, meaning they are not available via the DPS/ GMS schemes. This means they are not classified as High Techs, unlike biologics for other conditions. In Ireland, biologics for asthma are paid for directly out of hospital budgets, which limits their availability, as hospitals only have limited budgets, meaning respiratory consultants have to limit prescribing dependant on budget.

Access to biologic therapy for patients is regulated by the HSE via a strict protocol which consultants must abide by; the cost of the drug is taken from their hospital’s allocated budget for biologics. This has led to a so-called ‘post-code lottery’ regarding access to biologics because depending on the hospital the patient attends and the part of the country they live in, access will vary and is largely dependent on individual hospital budgets.

Whilst mepolizumab and benralizumab are available in auto-injector pens to facilitate patient self-administration

in other countries, these devices are

not yet approved for use in Ireland,

so biologic therapies must be administered by a specialist nurse in supervised settings in Ireland, which further reduces patient access.

The Asthma Society of Ireland is leading a campaign for the Government to expand the national fund for biologic medication for severe asthma to allow greater patient access. The Asthma Society of Ireland is also asking the Government to add asthma to the Long-Term Illness scheme, meaning patients would be able to access all asthma medication for free. ?

Disclaimer: Brands mentioned in this article are meant as examples only and not meant as preference to other brands.