Once you have distinguished a migraine from a ‘regular’ headache, it helps the treatment process to establish what type of migraine is happening

One of the most important first steps in the successful management of headache is diagnosing whether migraine is or is not the cause of the headache. Migraine is quite distinct from other headache types in how it presents and in how an episode evolves, attacks, and subsides. I last discussed migraine in Irish Pharmacist in 2022 (including how to distinguish from other types of headaches and all the types of painkillers used), so for this article, I concentrate solely on migraine.

PART 1: COMMON SYMPTOMS AND TYPES

The word ‘migraine’ derives from a Greek word hemikrani (half-skull), which literally means ‘pain on one side of the head’. This accurately describes and differentiates migraine from other types of headaches, as typically, it presents on one side of the head. An attack may consist of some or all the following symptoms:

MIGRAINE WITHOUT AURA (AROUND 80 PER CENT OF ALL ATTACKS):

- Moderate-to-severe pain, throbbing one-sided headache aggravated by movement.

- Nausea and/or vomiting.

- Hypersensitivity to external stimuli (ie, noise, smells, light).

- Stiffness in neck and shoulders.

- Pale appearance.

MIGRAINE WITH AURA (IN ADDITION TO ABOVE SYMPTOMS):

- Aura — around 20 of sufferers experience visual disturbances prior to the headache lasting up to one hour (most commonly blind spots, flashing light effect or zigzag patterns; may also include physical sensations such as unilateral pins and needles in fingers, arm and then face).

- Blurred vision.

- Confusion.

- Slurred speech.

- Loss of co-ordination.

OTHER TYPES:

Basilar migraine

Usually affecting teenage girls, this is a rare form of migraine that presents additional symptoms such as loss of balance, fainting, difficulty speaking and double vision. There can be loss of consciousness during an attack.

Hemiplegic migraine (sporadic or familial)

Usually beginning in childhood, this severe form of migraine causes temporary unilateral paralysis. May also feature extended aura period that could last for weeks. Generally related to a strong family history of the condition. It is a rare form of migraine; diagnosis usually requires a full neurological exam, as the symptoms may be indicative of other underlying conditions.

Ophthalmoplegic migraine

In addition to headache, this very rare form of migraine shows additional symptoms, such as dilation of the pupils. Inability to move the eye in any direction, as well as drooping of the eyelid, occurs. It occurs primarily in young people and is caused by weakness in the muscles which move the eye.

Abdominal migraine

Symptoms are usually nausea- and stomachrelated rather than headache. Occurs predominantly in children, usually evolves into typical migraine with age.

MIGRAINE TRIGGERS

A myriad of trigger factors, whilst in themselves not the cause of migraine, can build, bringing an individual to the point where a migraine attack is imminent.

Again, these can be different for everyone and indeed, may differ for an individual each time depending on their situation; trying to track down specifics can be difficult. The most common triggers include:

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS

Just moving around doing normal day-today things can be a potential danger for someone susceptible to migraine.

- Bright or flickering lights (could be cinema, shop displays or sunlight through trees whilst driving).

- Certain types of lighting (fluorescent, strobe).

- Strong smells (especially perfume, paint, etc).

- Weather (variety of factors, ie, bright sun glare, muggy close days, humidity).

- TV/computer screens and monitors.

- Loud and persistent noise.

- Travel areas of pressure change, ie, altitude.

DIETARY TRIGGERS

Research indicates about 20 per cent of migraine attacks are brought on by dietary factors. Whilst people believe this to be the case, actual scientific evidence proving a link is virtually non-existent. In many cases, there may be other factors that precede consuming a ‘suspect’ food, that could contribute more to the onset of an attack, ie, lack of sleep, skipping meals. The most cited link is foods which are high in the amino acids tyramine and/or phenylethylamine, such as:

- Cheese (fermented, aged, or hard mouldy types).

- Chocolate.

- Alcohol (beer and red wine particularly).

- Nitrites (common in processed meats).

- Sulphites (ie, preservatives in dried fruit and red and white wine).

- Additives (MSG).

- Aspartame (diet drinks).

- Caffeine (coffee, tea, etc; although caffeine can be used to prevent migraine, it is down to personal tolerance).

HORMONAL TRIGGERS

Once females move into puberty and then adulthood, hormones play an increasing role in migraine prevalence. Oestrogen fluctuations due to menstruation or using oral contraceptive pills or HRT can sometimes trigger migraine. Conversely, migraine susceptibility can decrease during pregnancy when oestrogen levels are high. In the main, migraine attacks lessen post-menopause (although can increase in the years preceding it). Identifying triggers can be the single most important step an individual can take in helping themselves to manage their condition. A diary noting possible triggers including diet, sleep and other events, including symptoms, is important when seeing a doctor for treatment, as it will help the doctor better identify the type of migraine (or if it is even migraine) and better help manage treatment. It may not be necessary to avoid situations completely, but instead build levels of awareness so that appropriate preventative steps and actions can be taken.

PART 2: MEDICATION FOR MIGRAINE

Ideally, advise on promotion of self-help, self-management, and other treatments to help improve the condition and add value to the benefit offered by medication.

Given the wide and varied nature of chronic pain, there can be a myriad of medication options. The effectiveness of medication depends on the nature and severity of the pain. It is important that non-medication management options are considered, including exercise, relaxation therapies (especially for the likes of tension headaches), physiotherapy, and cognitive behavioural therapy, just to name a few.

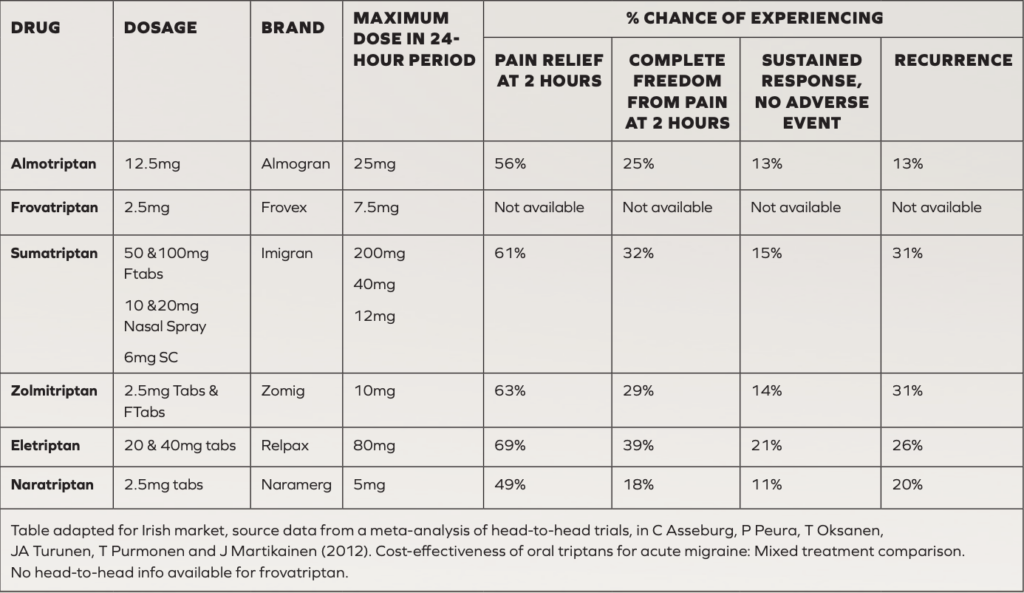

TRIPTANS

Regarding treatment of chronic pain caused by migraine, in addition to standard paracetamol and NSAIDs, triptans are considered the most effective to combat acute attacks if ordinary analgesics do not work. All are POM, apart from sumatriptan, with an OTC version recently becoming available in Ireland.

PREVENTATIVE MEDICATION FOR MIGRAINE

Prophylactic medication may be considered if the patient has taken adequate lifestyle steps to prevent migraine, such as using a diary to determine triggers and avoidance of these triggers, but the migraine continues. It would be reasonable for a prescriber to consider prophylaxis for migraine if a patient must use analgesics for eight or more days of the month. Prophylactic medication should be tried for four-to-six months at a reasonable dose to determine if it is working effectively. Prophylactic medication has potential side-effects that can limit dose or use. Amitriptyline, topiramate and flunarizine are the three most prescribed migraine prophylactic drugs, with amitriptyline being the most prescribed. Other prophylactics such as sodium valproate, pregabalin, gabapentin and pizotofen are considered second-line (often only used if the first three are not tolerated or ineffective).

Amitriptyline

A traditional tricyclic antidepressant, but not used much for depression due to sideeffects such as drowsiness, constipation, dry mouth, vivid dreams or nightmares and risks in people with glaucoma. It is dangerous in overdose. Low dose may be effective in preventing migraine; the dose for migraine varies between 10mg-to-150mg but the lower the better, and it should only be titrated up slowly. Use for six months at maximum tolerated dose before considering changing.

Topiramate

Topiramate is traditionally an epilepsy drug that is sometimes used in low-dose form to prevent migraine. It must be used in caution in those with liver or kidney problems and must be avoided in pregnancy. Possible side-effects include nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhoea, decreased appetite, drowsiness and sleeping problems. Highest daily dose of 700mg but for migraine, recommended dose is 25mg to 200mg twice daily. Starting dose is 25mg at night for twoto-eight weeks and increase gradually.

Propranolol (Inderal)

This is an old-style beta blocker traditionally used for angina and blood pressure but is rarely used for these indications nowadays due to safer, never versions of beta blockers with less sideeffects. However, in low doses, it is used for migraine prophylaxis in some. It should be used in caution in people with asthma, COPD, some heart problems, and diabetes. Side-effects can include cold hands and feet, pins and needles, tiredness and sleeping problems.

Flunarizine (Sibelium)

Flunarizine can take months to see a significant reduction in symptoms. Patients should be regularly reviewed to assess their response to this preventive treatment, and if a sustained attack-free period is established, interrupted flunarizine treatment should be considered.

Flunarizine maintenance treatment

If the patient is responding satisfactorily to flunarizine and a maintenance treatment is needed, the same daily dose should be used, but this time interrupted by two successive drug-free days every week, ie, Saturday and Sunday. Even if the preventative maintenance treatment is successful and well tolerated, it should be interrupted after six months and it should be re-initiated only if the patient relapses. Treatment is started at 10mg daily (at night) for adult patients aged 18-to-64 years and at 5mg daily (at night) for elderly patients aged 65 years and older. It is good practice to start at 5mg for all patients before titrating up. Side-effects include increased weight, increased appetite, depression, insomnia, constipation, stomach discomfort, and nausea.

Gabapentin

Like topiramate, gabapentin is traditionally an epilepsy drug. It may be used if topiramate, flunarizine or propranolol are not effective or tolerated. However, in recent years, studies have indicated that gabapentin may not be as effective for preventing migraine as first thought. Side-effects can include dizziness, drowsiness, appetite increase, weight gain and suicidal thoughts. Sodium valproate is another epilepsy drug occasionally used for migraine prevention if other prevention options fail or are not tolerated. Other preventative medicines include Pizotifen (Sanomigran) and Pregabalin (Lyrica).

Riboflavin (vitamin B2)

There has been some indication that vitamin B2 supplementation may help prevent migraine; however, this has not been proven.

Botox

Botox injections were introduced in recent years as a preventive treatment for chronic migraine. It is administered in 30-to-40 injection sites located across seven head and neck muscle groups. It is administered every 12 weeks, as its effect wears off after this period. It should be administered by doctors specialising in administering Botox for migraine, as it is more complicated than simply administering Botox to points on the skin, as is done for its anti-wrinkle effect on the likes of the forehead. Patients need two bouts of Botox injections to be able to determine it is working. While Botox use for migraine has varying degrees of success, it is shown to be successful (headaches cut in half) in 30-to-50 per cent of patients after two rounds of treatment, and this may increase to 70 per cent success rate in patients after five rounds of Botox. Botox reduces migraine by reducing neurotransmitter signalling in the brain. The patient may still be prescribed other preventative drugs for migraine even if getting Botox treatment.

NEW MIGRAINE DRUGS

A new class of migraine preventive drugs called anti-CGRPs are monoclonal antibodies come to market. These antibodies inhibit the action of a neurotransmitter called calcitonin gene-related peptide. The four CGRP inhibitors are erenumab, fremanezumab, eptinezumab and galcanezumab. The two CGRP inhibitors currently licenced in Ireland are erenumab (Aimovig) and fremanezumab (Ajovy) and are subject to a strict protocol for prescribing.

CGRP – ITS ROLE IN MIGRAINE

The neurotransmitter calcitonin gene-related peptide, or CGRP for short, plays a role in migraine. Its role in migraine includes:

- Being released in the trigeminal nerve.

- Increasing level occurs during migraine attacks.

- It dilates blood vessels.

- It reduces mast cells (cells that control inflammation during allergic reactions).

- Causes an inflammatory fluid in blood vessels.

For this reason, CGRP inhibitors are effective in reducing migraine.

ERENUMAB

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) authorised erenumab (Aimovig) in June 2018. It was the first monoclonal antibody to work by blocking the activity of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) for use for the prevention of migraine. Erenumab is licensed for prevention of migraine in adults who have migraines a minimum of four days per month. The dose is a subcutaneous 70mg injection every four weeks. If not controlled with 70mg every four weeks, the dose may be increased to 140mg every four weeks. Studies show erenumab is effective at reducing the number of days migraines occur. The most common side-effects with erenumab (up to one-in-10 people) are reactions at the site of injection, constipation, muscle spasms and itching. If the patient gets side-effects, they are normally mild.

NCPE: COST EFFECTIVENESS FINDINGS FOR ERENUMAB (AIMOVIG)

In January 2019, the NCPE considered the comparative clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness of erenumab (Aimovig) for the prevention of migraine in adults who have at least four migraine days per month. Concluding, the NCPE recommended erenumab for reimbursement at both the 70mg monthly dose and 140mg monthly dose for chronic headaches. They recommended that erenumab only be prescribed for chronic migraine patients who have tried three or more prophylactic treatments unsuccessfully. The NCPE did NOT recommend the reimbursement of erenumab for episodic migraine (less regular migraine) due to cost effectiveness concerns.

FREMANEZUMAB

In September 2020, the NCPE recommended fremanezumab (Ajovy) for the prevention of migraine in adults with chronic migraine who have tried three or more preventative treatments unsuccessfully. In 2021, the HSE Drugs Group via the HSE’s Managed Access Protocol (MMP) allowed access to eligible patients to the two CGRP inhibitors licenced in Ireland. Compared to erenumab, fremanezumab offers the flexibility of either monthly dosing (225mg once monthly), or quarterly dosing (675mg every three months).

HSE MANAGED ACCESS PROTOCOL FOR CGRP INHIBITORS

The HSE’s Managed Access Protocol (MMP) allowing access to eligible patients to the two CGRP inhibitors licenced in Ireland was approved by the MMP in October 2021. For the two CGRP inhibitors licenced in Ireland — fremanezumab (Ajovy) and erenumab (Aimovig):

- HSE has the High-Tech Protocols for prescribing the treatments, meaning these medications may be prescribed only by consultant neurologists who have agreed to the terms of the HSE-Managed Access Protocol.

- GPs cannot prescribe them. The patient must have failed to get adequate treatment response from at least three of the following drugs before CGRP inhibitors can be prescribed:

- Amitriptyline/nortriptyline.

- Botulinum toxin type A (Botox)

- Candesartan.

- Flunarizine.

- Metoprolol/propranolol.

- Pizotifen.

- Sodium valproate.

- Topiramate venlafaxine.

PART 3: KEY POINTERS: MIGRAINE OR NOT?

Pharmacists can be asked if the patient’s headache(s) is migraine or not. If a patient has a definitive diagnosis of migraine from their GP or neurologist, the treatment plan is relatively well mapped-out. A challenge for pharmacists and other health professionals is advising on adequate pain relief for patients not yet diagnosed with migraine; for example, a pharmacist cannot sell OTC sumatriptan to a patient not previously diagnosed with migraine. As I alluded to earlier, it can be hard to distinguish between migraine and other headaches.

KEY DISTINGUISHING FACTORS: NEUROLOGICAL SYMPTOMS

While migraine is known to most as a ‘headache’, headache is only one symptom of a larger problem. Migraine is classed as a neurological disease, meaning for many patients, in addition to severe headache, it also leads to incapacitating neurological symptoms. Neurological symptoms of migraine can include some or all the following:

- A severe throbbing-type headache.

- Visual disturbances (known as an aura).

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Extreme sensitivity to light, touch, and smell.

- Dizziness.

- Paraesthesia in the face, ie, numbness, tingling in the face or extremities.

Neurological symptoms with migraine can occur without any headaches. In 15- to-20 per cent of migraines, neurological symptoms develop before head pain. About 4 per cent of migraine patients do not have any headaches, meaning they only present with some of the neurological symptoms described above (ie, classical migraine aura), making it very hard to diagnose.

MIGRAINE TYPICALLY AFFECTS ONE SIDE OF THE HEAD

Another distinguishing factor between migraine and non-migraine headache is that migraine typically only affects one side of the head, whereas other types of headaches tend to affect the whole head, ie, a tension headache usually affects both sides, cluster headaches often present around the eye. However, it must be borne in mind that for a minority of migraine patients, the headache can affect both sides of the head.

PAIN QUALITY

Another difference between migraine and non-migraine headache is the pain’s ‘quality’: A migraine headache tends to cause intense pain that is throbbing in nature that makes performing daily tasks very difficult.

MIGRAINE OFTEN ASSOCIATED WITH TRIGGERS

More so than other causes of headaches, migraine is often associated with a wide array of possible triggers that can bring on bouts of headaches. The following factors can trigger migraines:

- Bright lights or flickering lights.

- Emotional stress and anxiety.

- Certain foods and drink, ie, chocolate, cheese, alcohol, and cured meats.

Many of these foods contain tyramine, which is a known trigger for migraine.

- Changes in weather (humidity, heat, pressure).

- Hormonal changes in women.

- Loud noises.

- Irregular eating habits or skipping meals.

- Strong smells.

- Tiredness.

- Too much or too little sleep. In relation to migraine triggers, each patient is unique, and patients get to know over time which triggers to avoid.

References on request

Disclaimer: Brands mentioned in this article are meant as examples only and not meant as preference to other brands.