Diabetes is one of the fastest growing diseases in Ireland. On completion of this module, it is expected the reader will have an enhanced understanding of causes and risk factors, pharmacological therapies, self-help measures, and emerging therapy options. Aspects of the different types of diabetes are also synopsised.

he Diabetic Federation of Ireland estimates that there are currently more than 200,000 diabetics in Ireland and that over half of these have no idea they have diabetes. Some countries have a population prevalence of up to 6 per cent for diabetes.

What is diabetes?

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines diabetes mellitus as “a metabolic disorder of multiple aetiology, characterised by chronic hyperglycaemia, with disturbances of carbohydrates, fat, and protein metabolism resulting from defects in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both”.

Diabetes mellitus is a condition that occurs when the body cannot use glucose normally. Glucose is the main source of energy for

the body’s cells. The levels of glucose in the blood are controlled by the hormone insulin, which is made by the pancreas. Insulin helps glucose enter the cells.

Types

There are two types of diabetes ? type 1 and type 2. In type 1 diabetes, the pancreas does not make enough insulin. In type 2 diabetes, the body cannot respond normally to the insulin that is made, which is often called insulin resistance.

Type 1

This type of diabetes usually appears before the age of 40 and most often starts as a teenager. Type 1 diabetes is the least common of the two main types and accounts for between 5 and 15 per cent of all people with diabetes. You cannot prevent type 1 diabetes.

Type 2

In most cases this is linked with obesity. Obesity results in insulin resistance, which interferes with insulin’s action on glucose uptake and its effect on fatty acids and protein metabolism. This type of diabetes usually appears in people over the age of 40, though in South Asian and African-Caribbean people, it often appears after the age of 25. Recently, more children have been diagnosed with the condition, with some being as young as seven. Type 2 diabetes accounts for between 85 and 95 per cent of all people with diabetes.

Diabetes numbers continue to increase

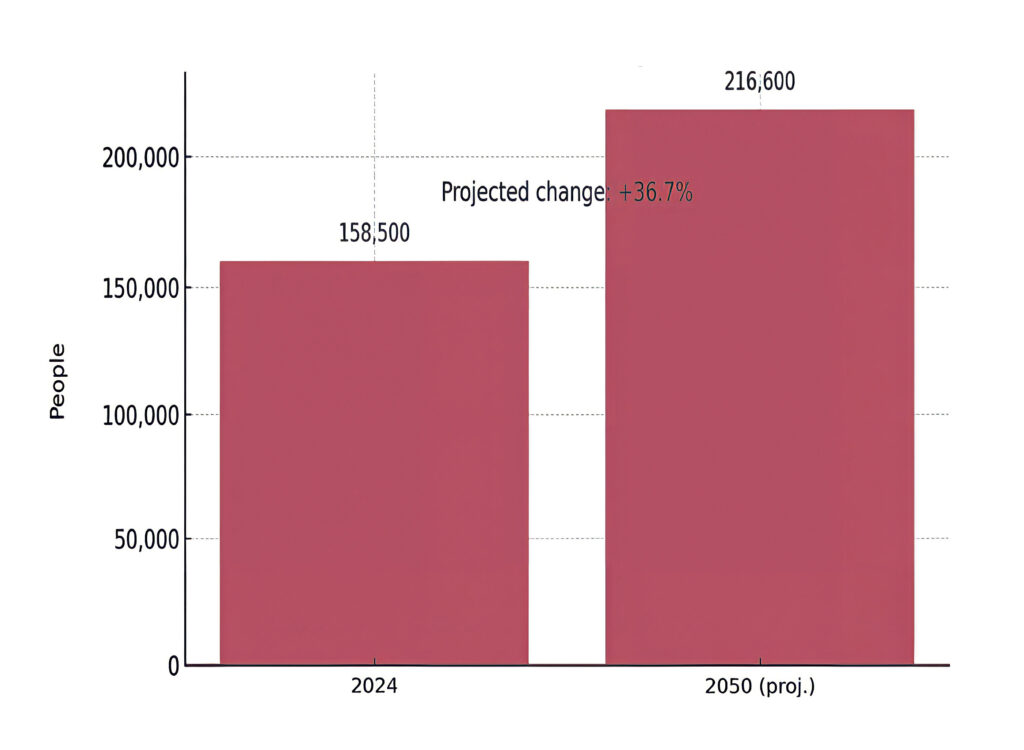

Diabetes continues to place a growing burden on public health in Ireland and across Europe. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) estimates that, in Ireland, more than 158,000 adults aged 20-to-79 were living with diabetes in 2024, a figure projected to exceed 216,000 by 2050.

This increase is not only driven by lifestyle risk factors such as obesity and inactivity, but also by Ireland’s growing and ageing population, which naturally increases the pool of people at risk. Diabetes contributes significantly to complications such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), kidney failure, and amputations. The chart in figure 1 illustrates these projected changes.

Diabetes-related health expenditure in Ireland vs UK and EU

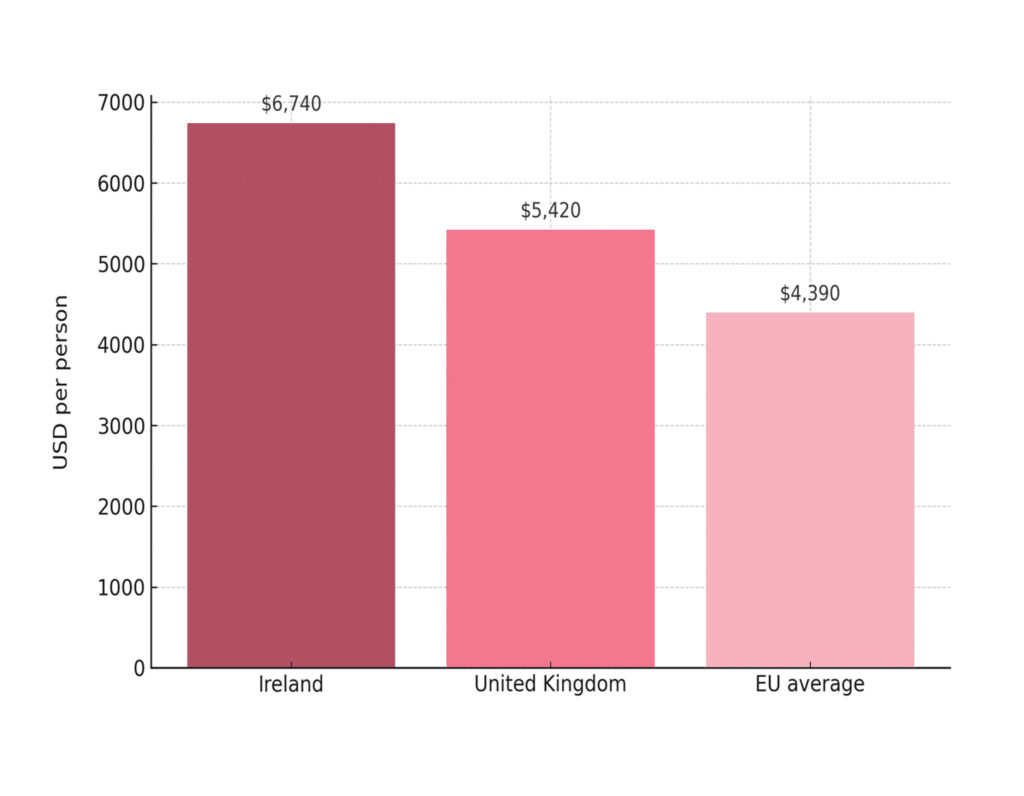

The financial burden of diabetes is significant, and Ireland consistently ranks among the highest in Europe for per-person costs.

Several factors explain Ireland’s higher spend. Firstly, the cost of medicines is greater, as Ireland has historically faced higher drug prices than many European neighbours, particularly for newer insulins and GLP-1 receptor agonists. Secondly, the management of diabetes complications, including hospitalisations for CVD, renal dialysis, amputations, and ophthalmology services, drives up costs.

Ireland also has a relatively fragmented primary care system, where access to structured diabetes programmes, while improving, remains uneven, leading to more hospital-based care. Finally, a smaller population base means overheads and specialist care costs are spread across fewer people, further inflating per-patient expenditure.

The chart in figure 2 illustrates how Ireland’s diabetes costs outpace those of nearby countries.

Diabetes symptoms

- Frequent urination.

- Excessive thirst.

- Extreme hunger.

- Increased fatigue.

- Irritability.

- Increased weight loss.

- Blurred vision.

- Genital itching or regular thrush.

- Slow healing of wounds.

Type 1 diabetes symptoms develop very quickly, usually over a few weeks. In people with type 2 diabetes, the signs and symptoms will not be so obvious or even non-existent. If you are older, you may put the symptoms down to the ageing process, thus preventing diagnosis.

Causes and risk factors

Type 1 diabetes

Type 1 diabetes develops when the insulin- producing cells in the pancreas have been destroyed. It is not known for sure why these cells become damaged, but the most likely cause is an abnormal reaction of the body to the cells, which may be triggered by a viral or other infection.

Type 2 diabetes

Risk factors are as follows:

Age: The risk of diabetes increases in patients over 40 or over 25 for African and Asian patients.

Family and ethnicity: Having diabetes in the family increases the risk of diabetes. The closer the relation is, the greater the risk. Also, people of Afro-Caribbean or South Asian origin are at least five times more likely to develop diabetes.

Weight: Over 80 per cent of people diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes are overweight. The more overweight and inactive the person is, the greater their risk of diabetes is.

Waist size: Women whose waist measures 31.5in (80cm) or more face an increased risk of diabetes. Men whose

waist measures 37in (94cm) or more face an increased risk of developing diabetes. Gestational diabetes: Pregnant women can develop a temporary type of diabetes called gestational diabetes. Having this, or giving birth to a large baby, can increase the risk of a woman going on to develop diabetes in the future.

Diabetes treatment

The aim of diabetes treatment is to do what the body once did automatically, which is to mimic the insulin pattern before diabetes and to keep blood sugar under control. For type 1 diabetes, insulin is always part of treatment as the body does not produce any insulin. In type 2 diabetes, your body still produces some insulin, so non-drug options or drugs may be used to help the body make better use of the insulin that it still produces.

Treatment of type 1 diabetes

There is no cure for type 1 diabetes, but it can be kept under control. Type 1 diabetes is controlled by administering insulin. This allows glucose to be absorbed into cells and converted into energy, stopping glucose from building up in the blood.

Treatment of type 2 diabetes

Many with type 2 diabetes can manage to control their condition simply by changing their lifestyle. Changes include:

Non-pharmacological treatment options

Diet

It is important to eat regularly three times a day. Special diabetic foods are not needed for a healthy diet. There is convincing evidence that progression from hyperglycaemia to type 2 diabetes can be prevented or, at least, delayed by dietary effort. A diabetes prevention programme in the US led to a 58 per cent reduction in the incidence of diabetes when participants were provided with lifestyle interventions, including diet, compared with a 31 per cent reduction in persons treated with metformin. However, there are relatively few other studies evaluating the effect of dietary intervention in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Controlling your blood sugar and weight is a vital part of managing type 2 diabetes; just as important as staying on top of any complications with your heart, eyes, and other organs which can occur due to the condition.

Managing type 2 diabetes requires a lot of dedication and meal planning to stabilise blood sugar (glucose) level.

If you do have type 2 diabetes, it is recommended you eat:

- Food from all food groups (carbohydrates, dairy, protein, fruit, and vegetables).

- The same amount of carbohydrates at every meal (portion control).

- Good fats (omega-3 fatty acids, monounsaturated fats).

- Fewer calories.

By eating a healthier and more balanced diet, you are more likely to keep blood sugars under control and maintain a healthy weight. Statistics indicate that an individual with type 2 diabetes is more likely to be overweight — but losing a stone in weight can help improve insulin sensitivity and glycaemic control. By incorporating heathy foods into your diet and keeping active (walking, swimming, tennis, etc) for 30 minutes three-to-four times a week, you can maintain your weight loss goal.

Foods to restrict include

Carbohydrates and blood sugar: Carbohydrates present in certain foods provide our bodies with the energy we require, although some carbohydrate foods can raise your blood sugar much higher and more quickly than other types of food. It is very important to identify which foods will lead to a spike in your sugar levels as these foods will need to be limited, ie, white versions of bread, rice, pasta, etc, will raise your blood sugar more quickly than healthier brown versions.

Sugary food: It goes without saying that sugary foods and drinks (fizzy drinks, sweets, biscuits, etc) are low-quality carbohydrates and need to be limited

or avoided if you have diabetes. These foods lack nutritional value and cause a sharp spike in your blood sugar level. This can lead to weight issues and worsen diabetic complications. Try and eat more fruits like apples, pears, and berries, as they contain fibre which can slow down the absorption of glucose, which is much more ideal for blood sugar control.

Fruit juice: While fibre-rich whole fruits are beneficial for controlling diabetes, fruit juice is not. If you have diabetes, it is not ideal to consume too much fruit juice as it contains a high level of concentrated fruit sugar, which can cause blood sugar levels to rocket.

White rice, pasta, and bread: This group of foods are refined starches, made with white flour, and are one of the worst foods you can consume if you are trying to regulate your blood sugar levels. These white carbohydrates are almost pure glucose and are recognised by your body as sugar once it begins to digest them. Opt for whole grains, such as brown rice and pasta, porridge, high-fibre cereals, and wholegrain breads.

Fatty cuts of meat: While meat itself will not interact with your blood sugar levels, it can increase your cholesterol and promote inflammation in the body. This means that an individual with diabetes is at greater risk of heart disease. Opt for lean protein choices such as fish, turkey, chicken, pork, and even lean beef. Always trim any visible excess fat from meat and do not eat more than two portions of red meat in a week.

Processed and pre-packed foods: Apart from the high levels of sugar which packaged snacks, baked goods, and white flour products etc have, they also contain trans fats. Trans fats increase LDL (bad) cholesterol and lower HDL (good) cholesterol, thus increasing the risk of heart disease. These trans fats are much more detrimental than saturated fat for an individual with diabetes. There is no level of trans fats which is considered safe to consume but under EU legislation, trans fats are thankfully now required to be shown on the food label, so identifying them is much easier.

Checking your food label is vital and keep an eye out for hydrogenated oils on ingredients labels as they are a major source of trans fats. Prioritise healthy fats from oily fish, nuts, seeds, avocado and oils like canola, flax, and olive.

Fried food: Fried foods are soaked in fat and oil which offer no nutritional benefits, only additional calories. Over-consumption of these types of foods means you are ingesting hydrogenated oils and trans fats, which can raise LDL cholesterol.

Plan your meals: Weighing your food will make meal planning and potion control easier. By planning meals, it means you are less likely to overindulge in food which can increase blood sugar.

- One-half of your plate should be vegetables and a small amount of fruit if you wish. Make sure to vary the colour and variety of fruit and vegetables, aiming for at least two portions. By having half your plate full of delicious vegetables, you are increasing your health and reducing the likelihood of developing diseases.

- One-quarter of your plate should be dedicated to carbohydrates. Choose wholegrain where possible (brown rice, brown pasta, unpeeled potatoes, quinoa).

- Protein should be the size of the palm of your hand. Protein source can be from animals such as chicken, turkey, fish, meat, and eggs or vegetables (ie, nuts, seeds, beans, lentil, and tofu). Throughout your day (and not only at dinner), aim to eat a good balance of animal and vegetable protein.

Wholegrain and fibre-rich foods: Some studies suggest that a diet rich in whole grains and high-fibre food can reduce the risk of diabetes by 35-to-42 per cent. Try to include the following foods in your diet as they help to stabilise your blood sugars and keep you fuller for longer:

Beans: Beans will raise your blood sugar levels slowly and over a long period of time. Where possible try to include high-quality carbohydrates with protein- rich beans (kidney, black, Lima, soy) as

it is an excellent combination to stabilise blood sugar levels and keep hunger at bay. Beans are also inexpensive, low in fat, and very versatile. Bear in mind that the sauces that are pre-mixed with beans (ie, baked beans) can be high in sugar so consume in moderation.

Porridge: Porridge oats are an ideal breakfast as they are a natural mood booster and a fibre-rich carbohydrate. Oats are also low GI (glycaemic index) foods, meaning they release sugars into your blood stream over a longer time, keeping you fuller for longer and regulating your sugar levels.

Fish: Combine fish with high-quality carbohydrates such as vegetables, lentils, and beans to keep your blood sugar from rising. Fish are also a great source of lean protein and contain very little fat — fats

in fish are in the form of omega-3 fatty acids which is an essential fat, vital for the development and functioning of the brain. The omega-3 present in salmon can help reduce the risk of heart disease, which is vital for an individual with diabetes whose risk of heart disease is already elevated. Oily fish such as wild salmon, sardines, and herring contain not only omega-3, but they also contain a healthy fat and protein combination which slows the body’s absorption of carbohydrates, and this will help stabilise blood sugar levels.

Yoghurt: An individual with type 2 diabetes should opt for low-fat dairy across the board, as this reduces the amount of saturated fats in the diet. Low-fat natural or Greek yoghurt contain both high-quality carbohydrates and protein. It is brilliant food for preventing a peak in blood sugar level. Calcium-rich foods are also known to be beneficial in preventing risks associated with type 2 diabetes. Watch out for hidden sugars in low-fat dairy products; always read the label; some sugars contain as much sugar per ml as Coke, so read the label. Bear in mind, 4g of sugar = one teaspoon, so if a small yogurt contains 12g of sugar, it has three spoonsful of sugar, so avoid.

Almonds: Almonds contain magnesium and monounsaturated fats. Anecdotal evidence suggests magnesium reduces risks of developing diabetes by about 33 per cent (true figure likely to be less), however for those with type 2 diabetes, including more magnesium-rich foods is advisable. Include foods like pumpkin seed, spinach, and almonds.

Vegetables: Vegetables contain a huge number of essential vitamins, minerals, and fibre. Vegetables such as broccoli, spinach, peppers, and mushrooms are high-quality carbohydrates and keep you fueled for a longer time. As they are low in calories and have a low impact on blood sugar, they are a vital component of any diabetes food plan. If you try to lose weight, this is one food group you can eat

At least half an hour of moderate activity, at least five days a week, is recommended

as much as you like.

Avocado: An avocado is an excellent food to eat, as it contains monounsaturated fats (considered one of the healthiest fats). A diet high in monounsaturated fats can improve insulin sensitivity and overall heart health. Avocado is a great alternative to mayonnaise in a sandwich — just mash up 1?4 and then spread. It is also great to bulk-up a salad.

Exercise

Exercise promotes healthy circulation and maintains a healthy weight. At least half an hour of moderate activity, at least five days a week, is recommended. A Cochrane review showed that exercise significantly improved glycaemic control and reduced plasma triglycerides and visceral adipose tissue, even without weight loss. A high level of leisure-type physical activity has been associated with a 33 per cent drop in fatal CVD, while moderate activity showed a 17 per cent drop compared with the most sedentary group.

Smoking

It is especially important for diabetics to quit smoking. This is because a diabetic already has a five-fold increased chance

of developing CVD or circulatory problems compared to non-diabetics. Smoking makes the chances of developing these diseases even greater.

Alcohol

There is no need to give up alcohol completely, but it is important to drink in moderation. Do not drink on an empty stomach. Eat food containing carbohydrates before and after drinking (as alcohol reduces glucose levels). Monitor blood glucose levels more regularly if drinking alcohol.

Pharmacological treatment options

If lifestyle changes alone do not reduce glucose levels, medication may be used to increase insulin production and strengthen its effect. All oral hypoglycemic drugs and insulin are safe in older patients, although each has some limitations in older people. ‘Start low and go slow’ is a good principle to follow when starting any new medications in an older adult.

Oral hypoglycemics

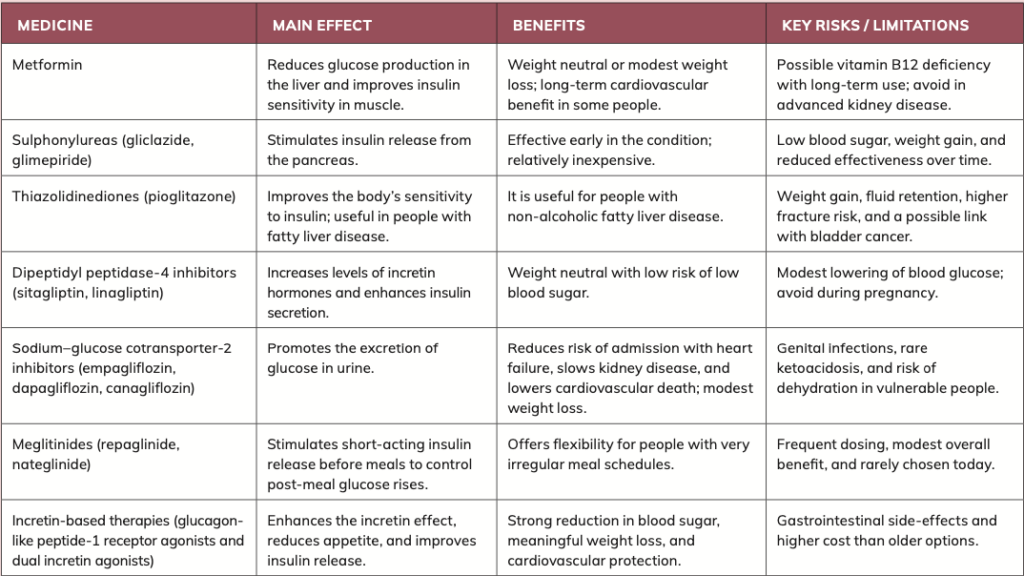

Metformin

Metformin improves the effectiveness of insulin by reducing glucose production in the liver and by improving the uptake and use of glucose in muscle. Because it does not stimulate the pancreas to release insulin, it is not associated with low blood glucose when used alone. It is generally weight?neutral or associated with less weight gain than many other diabetes medicines. Doses up to 3g per day can be used, titrated to effect and tolerability.

Gastrointestinal upset (for example, nausea, abdominal discomfort, or diarrhoea) is the most common side?effect and may occur in a substantial proportion of patients — slow dose titration and taking it with food can help. Metformin is an attractive choice for older adults because of the low risk of low blood glucose but it must be used with caution in the presence of reduced kidney function due to the rare risk of lactic acidosis — reassess kidney function regularly, particularly where serum creatinine appears normal, but true kidney function is reduced.

Sulphonylureas

Sulphonylureas stimulate the pancreatic beta cells to secrete insulin and are most effective in newly? or recently?diagnosed type 2 diabetes when endogenous beta?cell function is still present. They can substantially lower glycated haemoglobin, but low blood glucose is the most common adverse effect, particularly with older, long?acting agents. Weight gain can also occur. Modified?release gliclazide is often better tolerated in older adults than older long?acting agents. Treatment failure (loss of effectiveness over time) can occur as beta?cell function declines.

Thiazolidinediones

Thiazolidinediones (for example, pioglitazone) improve insulin sensitivity in adipose tissue, muscle, and liver. They are typically used in combination with metformin or with a sulphonylurea when other standard treatments are ineffective or not tolerated. They may also be licensed as single?agent therapy in some people who cannot take metformin. The full effect may take up to 12 weeks. They do not cause low blood glucose when used alone and can be used in people with reduced kidney function.

Important limitations include fluid retention, risk of worsening heart failure, possible increased fracture risk, weight gain, and cost considerations. Rosiglitazone was withdrawn from the European market in 2010 because of cardiovascular safety concerns. Use pioglitazone with caution in people with CVD or risks for heart failure.

Dipeptidyl peptidase?4 inhibitors

Dipeptidyl peptidase?4 inhibitors (ie, sitagliptin, linagliptin) increase levels of active incretin hormones, which enhances insulin release after meals and reduces glucagon secretion. They are generally weight?neutral and have a low risk of low blood glucose when not combined with insulin or sulphonylurea. They are usually well tolerated; however, long?term safety data in very elderly people are more limited than for older drug classes. Avoid use during pregnancy. Combination therapy with metformin is often well tolerated compared with combinations that include a sulphonylurea.

Sodium?glucose cotransporter?2 inhibitors Sodium?glucose cotransporter?2 inhibitors (for example, dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, canagliflozin) reduce the reabsorption of glucose in the kidney, increasing urinary glucose excretion. Benefits include once?daily oral dosing, modest weight loss, and reductions in blood pressure. They reduce the risk of kidney disease progression, cardiovascular events and mortality in appropriate patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) or CVD. Use with caution in people at higher risk of dehydration (for example, frail older adults or those who binge?drink alcohol). Consider reducing the dose of loop diuretics if combined. Avoid in pregnancy. Increased urinary glucose raises the risk of urinary tract infection and genital yeast infection (thrush). Risk of diabetic ketoacidosis is higher with very?low?carbohydrate or ketogenic diets — avoid such diets while on these medicines. Dose adjustments or interruption may be required in reduced kidney function.

Meglitinides

Meglitinides (for example, repaglinide) stimulate insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells and are short?acting, meal?time glucose regulators. They are taken one to 30 minutes before meals and require multiple daily dosing. They may be useful for people with irregular meal schedules (for example, shift workers). Gastrointestinal upset tends to be less than with metformin, but weight gain can occur (for example, up to approximately 3kg over three months in some reports). Because they are metabolised by cytochrome P450 enzymes, they have a higher potential for interactions with other medicines. Their use is limited in practice due to frequent dosing requirements and the convenience and outcomes profile of alternative oral agents.

Acarbose (Glucobay) (now gone off the market)

Acarbose lowers blood glucose by slowing the breakdown of some carbohydrates. Acarbose reduces the digestion and absorption of starch and sucrose by competitively inhibiting the intestinal enzymes involved in the degradation of disaccharides, oligosaccharides, and polysaccharides. The reduction in HbA1c is modest. The main side?effects which occur in over 10 per cent of patients (and which has limited its use) are flatulence and diarrhoea. The gastrointestinal side-effects are due to intra-colonic fermentation of the unabsorbed sugars and reduce with time.

Glucobay tablets were officially withdrawn on 17 August, 2020.

Contributing factors to the withdrawal of Glucobay

1. Commercial considerations: In other markets such as Canada, Glucobay was discontinued for commercial reasons, not due to safety or efficacy. There is no information I could find on the reason for withdrawal in Ireland, but commercial reasons are likely to have influenced the Irish withdrawal as it was rarely prescribed in the years before its withdrawal.

2. Side-effect profile and patient tolerability: Acarbose commonly causes gastrointestinal side-effects such as flatulence, diarrhoea, and abdominal discomfort. Long-term studies show that only 39 per cent of patients remained on acarbose after three years compared with 58 per cent on a placebo, highlighting tolerability issues. This was the biggest reason it was rarely prescribed, making it commercially unviable.

3. Liver safety concerns: Though rare, acarbose has been associated with liver enzyme elevations, hepatitis, jaundice, and even liver failure in isolated cases. Monitoring of liver enzymes was recommended in some regulatory environments, which also contributed to its low usage for treatment of diabetes.

4. Regulatory conditions and alternatives: Under Irish regulations, withdrawal notices must be given in advance depending on the availability of reimbursed therapeutic alternatives. The withdrawal was planned in compliance with HSE/Health Products Regulatory Authority (HPRA) requirements and that other antidiabetic options (ie, metformin, sulfonylureas, DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, SGLT-2 inhibitors) were accessible to patients.

Non-oral hypoglycemics

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) GLP-1 RAs remain one of the most important recent advances in type 2 diabetes management. These drugs mimic the action of the endogenous incretin hormone GLP-1, stimulating insulin secretion in a glucose-dependent manner, suppressing glucagon release, and slowing gastric emptying. The combined effect reduces post-prandial glucose excursions, improves glycaemic control, and contributes to weight reduction. Beyond glycaemia, the class has demonstrated cardiovascular and renal protection, placing it at the centre of modern diabetes guidelines.

Mechanism of action

GLP-1 RAs exert their therapeutic effect through three key pathways:

- Slowing gastric emptying: Delaying nutrient absorption and preventing rapid post-meal glucose spikes.

- Stimulating insulin secretion: Enhancing pancreatic beta-cell response to elevated glucose levels.

- Suppressing hepatic glucose output: Reducing inappropriate glucagon secretion and downstream glucose release.

These effects act synergistically without causing hypoglycaemia in monotherapy. However, risk increases when combined with insulin or sulfonylureas, and dose adjustments are recommended.

Current drugs and administration information

Several injectable GLP-1 RAs are available:

- Exenatide ? short-acting, twice daily (Byetta); and long-acting once weekly (Bydureon).

- Liraglutide (Victoza) ? once daily injection, also licensed at higher doses as Saxenda for obesity.

- Dulaglutide (Trulicity): Once weekly.

- Semaglutide: Weekly subcutaneous (Ozempic) and daily oral formulation (Rybelsus).

Gastrointestinal side-effects (nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea) remain the most common adverse events, often dose- dependent and transient. Discontinuation rates are low in real-world use once dose titration is carefully managed.

Expansion into obesity and weight management

Semaglutide (Wegovy) has become widely adopted globally as a treatment for obesity, including for use in patients without diabetes. Its approval for chronic weight management in many regions has blurred traditional boundaries between diabetes and obesity treatment.

Tirzepatide (Mounjaro), a dual GLP-1/ GIP receptor agonist (sometimes called a ‘twincretin’), has shown even greater efficacy, producing average weight loss of 15-to-20 per cent in trials. Although not a pure GLP-1 RA, it is frequently grouped with this class in practice. It became available in Ireland on private prescription in 2025, although it is not yet HSE-reimbursed.

This expansion has fuelled unprecedented public demand, leading to global shortages and supply issues. Pharmacists are now often at the frontline managing patients unable to access continuity of treatment.

Cardiovascular and renal outcomes Landmark trials and subsequent meta- analyses confirm that liraglutide, semaglutide, and dulaglutide significantly reduce major adverse cardiovascular events in high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes. More recently, semaglutide has also demonstrated benefits in slowing progression of CKD, making these drugs dual-purpose for metabolic and end- organ protection.

In 2024, the US Food and Drug Administration extended semaglutide’s license (Wegovy) to include treatment of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), the first GLP-1 RA approved for a liver indication, highlighting expanding therapeutic horizons.

Oral GLP-1 RAs

When I last wrote about diabetes in Irish Pharmacist in 2023, oral semaglutide (Rybelsus) was not reimbursable on the health scheme in Ireland, ie, Long Term Illness scheme. As of 2025, reimbursement remains limited due to National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics (NCPE) cost- effectiveness concerns.

The NCPE evaluates clinical and cost-effectiveness of new medicines and advises the HSE on reimbursement decisions for State drug schemes. Nonetheless, international uptake of oral Rybelsus has increased, particularly for patients unwilling or unable to inject. Ongoing trials are exploring once-weekly oral formulations to improve adherence.

Adverse events and safety

Gastrointestinal intolerance remains the main limiting factor, but emerging data suggests slower titration improves tolerability. Pancreatitis and gallbladder disease risks continue to be monitored — evidence suggests that there is only a small increased risk.

Retinopathy progression has been reported in some patients with rapid HbA1c lowering on semaglutide, necessitating ophthalmological monitoring in high-risk individuals.

Long-term safety surveillance (cardiovascular, pancreatic, thyroid) remains reassuring overall.

Guideline positioning

Both the American Diabetes Association (ADA) (2024 Standards of Care) and

NICE guidelines (NG28 update) now recommend GLP-1 RAs not only for glucose lowering but also as first-line add- on therapy where cardiovascular or renal risk is present. In obesity management, guidelines increasingly view semaglutide and tirzepatide as foundational therapy alongside lifestyle measures.

Future directions

Next-generation drugs: Research is underway into GLP-1/glucagon dual agonists and triple agonists targeting GLP- 1, GIP, and glucagon receptors.

Long-acting oral delivery: Novel oral semaglutide formulations with weekly dosing are in phase 3 trials.

Combination with SGLT2 inhibitors: Studies show complementary renal and cardiovascular protection, increasingly used in tandem.

Insulin and choice of therapy in type 2 diabetes

Insulin remains a cornerstone therapy in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, though its use in type 2 is now considered later in the pathway due to the increasing role of GLP- 1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors.

Nonetheless, insulin therapy is essential when oral or injectable non-insulin options are inadequate, when HbA1c remains high despite optimal use of other drugs, or when patients present with significant hyperglycaemia or catabolic symptoms.

Fast-acting and rapid-acting insulins

Insulin aspart (NovoRapid) and insulin lispro (Humalog) are commonly used rapid-acting analogues.

Onset and duration: Aspart acts within 10-to-20 minutes with a duration of three- to-five hours, while lispro acts within about 15 minutes with a duration of two- to-five hours.

Administration: They are typically injected immediately before meals, or just after if necessary. They may be delivered via multiple daily injections or insulin pumps.

These insulins are often combined with longer-acting insulins to provide a basal- bolus regimen. Biphasic combinations (ie, NovoMix 30, Humalog Mix25) offer both prandial (after meals) and basal (longer periods between meals) coverage in a single preparation, useful for patients requiring simpler regimens.

Long-acting and basal insulins

Two types in Ireland

- Insulin glargine (Lantus, Toujeo) and insulin detemir (Levemir) provide relatively flat 24-hour profiles, administered once daily.

- Insulin degludec (Tresiba), with an ultra- long action (>42 hours), allows more flexible dosing and has lower hypoglycaemia risk in some studies.

These are often preferred as basal options in type 2 diabetes requiring insulin add-on therapy, especially in older adults for whom once-daily regimens improve adherence and quality of life.

Insulin icodec (Awiqli): A potential game changer in terms of insulin therapy? In 2024, once-weekly insulin icodec (Awiqli) was licensed in the EU, offering a novel approach with a half-life of around 196 hours. NICE has not yet fully adopted it, but it represents a potential major shift in basal insulin management pending real-world outcomes.

The pros and cons of insulin icodec (Awiqli)

Pros: Awiqli (insulin icodec) offers the major advantage of once-weekly dosing, which may improve adherence compared with daily basal insulins. Clinical trials show it provides similar HbA1c and fasting glucose control to daily glargine, with no unexpected safety concerns. The reduced injection burden is particularly beneficial for patients struggling with daily therapy, enhancing treatment satisfaction and quality of life.

Cons: However, Awiqli is associated with a slightly higher rate of hypoglycaemia in some studies, particularly during dose titration. Long- term safety data are still limited given its recent approval, and switching from daily to weekly insulin requires careful education and monitoring. Its higher cost and restricted availability may also limit widespread adoption until real-world effectiveness and cost- effectiveness are fully established.

Launch in Ireland?

In May 2024, the HPRA authorised Awiqli 700 units/mL solution for injection (pre-filled pen) with a license. However, despite this license, it has not yet been released on the Irish market by manufacturer Novo Nordisk. In addition, no application has yet been made for approval on the Long-term Illness Scheme, so there is no date set for when it will become available in Ireland.

Uses of insulin uses in older patients

NICE advises that insulin should not be withheld in older patients solely due to concerns about complexity. With modern basal analogues, initiating once-daily insulin alongside oral drugs can substantially improve glycaemic control and quality of life in elderly patients with suboptimal control. Dose individualisation remains essential.

Safety and interactions

Drug interactions must be carefully considered. Concomitant drugs such as corticosteroids, thiazides, and thyroid hormones can increase insulin requirements, while ACE inhibitors, SSRIs, alcohol, and sulfonylureas can increase hypoglycaemia risk.

Hypoglycaemia risk: Beta-blockers may mask the typical adrenergic warning symptoms of low blood glucose, such as sweating, tremor, palpitations, and anxiety. This can delay recognition of hypoglycaemia and increase risk of severe episodes. Patients must be counselled on recognition and management. Weight gain is often less with newer basal insulins (ie, glargine, degludec) compared with isophane insulin.

Combination of insulin with GLP-1 receptor agonists

GLP-1 RAs can be combined with insulin under specialist supervision. NICE stipulates strict criteria for initiation (ie, BMI ?35 with high HbA1c, or where weight loss would benefit obesity-related comorbidity). Combination therapy improves glycaemia while offsetting insulin-associated weight gain but requires gradual insulin dose reduction to avoid diabetic ketoacidosis risk.

Which drug to choose? (NICE-aligned 2025)

NICE NG28 (last updated 2022-2024) places greater emphasis on individualised therapy, prioritising drugs with cardiovascular, renal, or weight benefits.

First-line therapy

Metformin remains first-line unless contraindicated or not tolerated.

Lifestyle intervention remains essential throughout therapy.

If HbA1c not controlled on metformin Choice depends on comorbidities:

- Established CVD, high CV risk, or CKD: Add an SGLT2 inhibitor with proven CV/ renal benefit (empagliflozin, dapagliflozin). GLP-1 RA, considered where weight loss is also a key target.

- Without CVD or CKD: Options include DPP-4 inhibitors, pioglitazone, sulfonylureas, or SGLT2 inhibitors. Selection is based on weight, risk of hypoglycaemia, cost, and patient preference.

If HbA1c remains uncontrolled on dual therapy

Triple therapy (ie, metformin + SGLT2i + DPP-4 inhibitor, or metformin + sulfonylurea + pioglitazone). Alternatively, progress to injectable therapy.

Injectable therapy choices

GLP-1 RA preferred before insulin where BMI ?35 or weight loss is a priority.

Insulin indicated if HbA1c remains high despite oral/injectable therapy, or if symptomatic hyperglycaemia is present.

Start with basal insulin (ie, glargine, degludec, detemir) once daily. Progress to basal bolus if targets unmet.

Changes to the treatment algorithm

In the past two years (based on updated NICE guidance)

I last wrote about diabetes in Irish Pharmacist in 2023. There have been a few treatment guidance changes issued by NICE since then. The 2025 treatment algorithm is patient-centred, emphasising comorbidity-driven drug selection. Metformin remains foundational, but SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 RAs have overtaken sulfonylureas and thiazolidinediones as preferred second-line drugs, especially in patients with cardiovascular or renal disease. Insulin remains indispensable but is generally reserved for later stages, with basal analogues.

Active kidney disease

2025 Update: Chronic kidney disease (CKD) management

This is an updated pharmacist summary on CKD management as of 2025, reflecting recent guidance from NICE, KDIGO, and emerging trial data. Abbreviations have been removed for clarity and readability.

What is new? (2024-2025)

Empagliflozin is now recommended by NICE for CKD. It should be added to an optimised treatment plan including angiotensin- converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, provided specific kidney function and proteinuria thresholds are met. The least expensive sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor should be used when clinically suitable.

Dapagliflozin guidance was updated in July 2025. The treatment criteria are now aligned with empagliflozin, allowing use in patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 20 millilitres per minute per 1.73 square metres, provided proteinuria or type 2 diabetes is present.

The Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2024 guidance advises starting a sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor from an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 20 or higher, and continuing treatment as kidney function declines, if tolerated.

Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists are gaining recognition for kidney protection. The FLOW trial

showed semaglutide reduced kidney and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes with CKD. Regulatory authorities in Europe have added kidney protection to the Ozempic label as of December 2024. The American Diabetes Association 2025 guidelines reflect this development, recommending glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists when sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors are not tolerated or not sufficient.

What still stands (from earlier advice) Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers at the maximum tolerated licensed dose remain first-line therapy for albuminuric CKD. They are essential for blood pressure control and reduction of protein in the urine.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors remain central in reducing progression of CKD and lowering cardiovascular risk. They are now routine add-on therapy in eligible patients, both with and without diabetes, as confirmed by NICE guidance.

Hypertensive control for diabetics

Why blood pressure control matters in diabetes

Hypertension together with diabetes markedly increases the risk of CVD,

including stroke, coronary heart disease, heart failure, and peripheral vascular disease. It also increases overall mortality. Effective blood pressure control reduces both macrovascular and microvascular complications and is a core priority alongside the management of blood glucose in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Diagnosing hypertension and when to start treatment (based on NICE guidance)

Confirm a diagnosis of hypertension using ambulatory blood pressure monitoring or home blood pressure monitoring when the clinic blood pressure is equal to or above 140 over 90 millimetres of mercury.

The diagnostic threshold using daytime ambulatory or home monitoring is typically an average equal to or above 135 over 85 millimetres of mercury.

Measure blood pressure at least annually in people with diabetes if hypertension or kidney disease has not been previously diagnosed.

When to start treatment:

Stage 2 hypertension (equal to or above 160 over 100 in the clinic): Treat all adults.

Stage 1 hypertension (140 over 90 to 159 over 99 in the clinic): Offer treatment in adults under 80 years who have diabetes, kidney disease, target-organ damage, established CVD, or a 10-year cardiovascular risk of at least 10 per cent. Consider treatment in adults under 60 years even if the calculated risk is under 10 per cent.

Blood pressure targets (what to aim for):

- Adults under 80 years (with or without type 2 diabetes): Clinic target less than 140 over 90 millimetres of mercury (approximately less than 135 over 85 by ambulatory or home monitoring).

- Adults 80 years and older: Clinic target less than 150 over 90 millimetres of mercury; use clinical judgment in the presence of frailty or multiple long-term conditions.

Assess for postural hypotension in people with diabetes, in older adults, or in anyone with symptoms such as dizziness on standing. If a significant postural drop is present, aim treatment to the standing blood pressure.

Type 1 diabetes: General target 135 over 85 millimetres of mercury; if albumin in the urine is increased or if at least two features of the metabolic syndrome are present, consider a lower target of 130 over 80 millimetres of mercury, with individualisation to the person.

First?line medicine choices (stepwise, based on NICE)

Step 1: For adults with type 2 diabetes (any age or family origin): Offer an angiotensin?converting enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker as the first?line option. If an angiotensin?converting enzyme inhibitor is not tolerated (for example, because of cough), use an angiotensin receptor blocker instead. Do not combine an angiotensin?converting enzyme inhibitor and an angiotensin receptor blocker together.

For adults without type 2 diabetes: Follow the age and ethnicity pathway (angiotensin?converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker if under 55 years; a calcium?channel blocker if

55 years or older or of Black African or African?Caribbean family origin).

Step 2: If blood pressure remains above target on step 1, add either a calcium?channel blocker or a thiazide?like diuretic to an angiotensin?converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker; or add an angiotensin?converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker or a thiazide?like diuretic to someone who started with a calcium?channel blocker.

Step 3: Triple therapy — combine an angiotensin?converting enzyme inhibitor

or angiotensin receptor blocker with a calcium?channel blocker and a thiazide?like diuretic at the highest tolerated doses.

Step 4 (resistant hypertension): Confirm resistance using ambulatory or home monitoring, check adherence, and assess for a postural drop.

Consider low?dose spironolactone if the serum potassium concentration is 4.5 millimoles per litre or lower (and monitor urea and electrolytes one month after starting). If the potassium concentration is above 4.5 millimoles per litre, consider an alpha?blocker or a beta?blocker.

Seek specialist advice if blood pressure remains uncontrolled.

Diabetes, kidney disease, and renin? angiotensin?aldosterone system blockade In CKD with diabetes, an angiotensin?converting enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker is advised and increase the dose to the highest licensed and tolerated dose, particularly when albumin in the urine is increased. Monitor estimated glomerular filtration rate and the albumin?to?creatinine ratio regularly and reinforce ‘sick?day’ rules to pause medicines during dehydrating illness to reduce the risk of acute kidney injury.

Blocking the renin?angiotensin? aldosterone system is central where albumin in the urine is increased. Combine with lifestyle measures and individualised blood pressure targets.

Lifestyle and monitoring (high?impact essentials) Encourage home blood pressure monitoring with education on correct technique — this improves control and engagement.

Emphasise salt restriction, weight management, regular physical activity, moderation of alcohol intake, and smoking cessation at every review.

Review over?the?counter or complementary medicines that may raise blood pressure or interact with therapy, such as non?steroidal anti?inflammatory drugs, decongestants, and liquorice.

Medicine safety and counselling in diabetes

Risk of low blood glucose and beta?blockers: Beta?blockers may mask the typical adrenergic warning symptoms of low blood glucose, including sweating, tremor, palpitations, and anxiety, which can delay recognition. Advise frequent glucose checks and carrying fast?acting carbohydrate.

Thiazide?like diuretics: Monitor for low sodium, low potassium, and effects on blood glucose and blood lipids.

Angiotensin?converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers: Check urea and electrolytes after starting and after dose changes; advise temporary suspension during dehydrating illness (so?called ‘sick?day’ rules). Postural hypotension: Advise slow position changes; review other medicines that lower blood pressure (for example, sodium?glucose cotransporter?2 inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and tamsulosin) and encourage good hydration.

What has changed compared with older practice?

Advice has changed in recent years. Targets have been harmonised: Most adults with diabetes now share the same clinic targets as adults without diabetes (less than 140 over 90 millimetres of mercury if under 80 years; less than 150 over 90 millimetres of mercury if 80 years or older), with the type 1 diabetes exceptions described above.

Earlier and explicit use of medicines that block the renin? angiotensin?aldosterone system: An angiotensin?converting enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker is now clearly the first?line option for all adults with type 2 diabetes at step 1.

The pathway for resistant hypertension is clarified: Add spironolactone where the potassium level allows; otherwise use an alpha?blocker or a beta?blocker; seek specialist input if blood pressure remains uncontrolled.

Quick guide for pharmacists based on NICE guidance

Diagnose: Clinic blood pressure equal to or above 140 over 90 millimetres of mercury should be confirmed with ambulatory or home monitoring (average equal to or above 135 over 85).

Treat: Anyone with type 2 diabetes and persistent stage 1 hypertension should be offered treatment; an angiotensin?converting enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker is first?line.

Targets: Less than 140 over 90 millimetres of mercury if under 80 years; less than 150 over 90 millimetres of mercury if 80 years or older; consider postural blood pressure.

Albumin in the urine or CKD: Use an angiotensin?converting enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker to the maximum tolerated dose and monitor the albumin?to?creatinine ratio and the estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Statin therapy in diabetes and cardiovascular risk Diabetes is recognised as a major risk factor for CVD, and current NICE and international guidelines recommend proactive use of statins in this population. Adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes have a substantially increased lifetime risk of atherosclerotic events, including myocardial infarction and stroke. NICE guidance (NG238, 2023) advises offering atorvastatin 20mg daily for primary prevention in people with type 2 diabetes who are aged over 40, have had diabetes for more than 10 years, have established nephropathy, or have additional CV risk factors such as hypertension or smoking. For secondary prevention, higher?intensity statins (atorvastatin 80mg or equivalent) are usually indicated.

For lipid management, NICE recommends focusing on the percentage reduction in non?HDL cholesterol rather than fixed thresholds. A ?40 per cent reduction from baseline is the target after three months of therapy. In general practice, many clinicians aim for non? HDL cholesterol <2.5mmol/L or LDL cholesterol <1.8mmol/L in patients at very high cardiovascular risk (such as those with existing CVD, CKD, or multiple risk factors).

Shared decision?making is essential, with clear counselling about common adverse effects such as myalgia, and reassurance that the benefits in CV risk reduction far outweigh the risks. Statins are safe in diabetes and reduce the risk of both first and recurrent CV events.

Pharmacy teams can support adherence, monitoring, and lifestyle advice to help patients achieve lipid goals.

References available on request

Disclaimer: Brands mentioned in this article are meant as examples only and not meant as preference to other brands.