Eamonn Brady MPSI provides an overview of the various factors to be considered in assessing and managing hypertension

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the number-one cause of death worldwide. Hypertension is the leading cause of CVD; it is responsible for 51 per cent of total global mortality from stroke and 45 per cent of mortality from ischaemic heart disease. The amount of adults with raised blood pressure increased from 594 million in 1975 to 1.13 billion in 2015. In Ireland, CVD is responsible for approximately 10,000 deaths each year, which is equivalent to 36 per cent of all deaths.

According to a study by TILDA in 2015, hypertension (high blood pressure) affects up to 64 per cent of the over-50s in Ireland. Hypertension is generally asymptomatic, therefore routine checks are essential, especially for those over 50. Blood pressure was traditionally measured with a sphygmomanometer, which used the height of a column of mercury to reflect the circulating pressure. Today, BP values are still reported in millimetres of mercury (mmHg), though aneroid and electronic devices do not use mercury.

Causes

The cause of hypertension in 90-to-95 per cent of all cases is unknown, known as ‘primary hypertension’. Secondary high blood pressure is hypertension that is caused by a known medical condition (rare). Secondary hypertension can be caused by adrenal disease, ie, Cushing syndrome, kidney disease and the use of some medications, such as NSAIDs (ibuprofen and diclofenac), steroids, amphetamines and cocaine.

There is evidence that hypertension runs in families, but this can also be due to behavioural reasons learned or acquired from families, such as heavy drinking. Race can also influence high blood pressure. For example, there is a much higher incidence of hypertension in the black African and African-Caribbean population.

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure

The systolic blood pressure (SBP) is the top number on the reading. It is the peak pressure of blood in the arteries as the ventricles pump blood out of the heart to the rest of the body. Diastolic blood pressure (DBP) is the bottom number on the reading. It is the minimum pressure in the arteries as the heart relaxes and the ventricles can refill with blood. Both diastolic and systolic pressure are important risk factors for CVD. Historically, greater emphasis was placed on diastolic values, but systolic is now considered the better predictor of CVD risk.

120mmHg systolic and 80mmHg diastolic is considered normal blood pressure. SBP continues to increase between the ages of 30 and 84 and over, while DBP increases until the age of 60, then decreases until at least 84 years of age. Isolated systolic hypertension (elevated systolic but not diastolic pressure) is the most prevalent type of hypertension in those aged 50 and over.

Measuring hypertension

The most accurate method of measuring blood pressure is the use of upper-arm monitors. Healthcare providers must ensure monitors are regularly recalibrated and maintained. Allow the patient to sit comfortably for five-to-10 minutes in a quiet room before measuring his/her blood pressure. Make sure the cuff is the correct size. Ensure clothing does not restrict the arm, ie, place the cuff on bare skin, not clothing. If the arm tightens with rolled-up clothing, the arm may need to be slipped out of a sleeve. The patient should sit with back straight and supported; legs not crossed and have had no caffeine, tobacco and alcohol within the previous half hour.

The arm should be positioned at heart height, ie, sitting on a chair with arm resting on table, the palm of the hand facing upwards. Blood pressure should be measured in both arms as many patients, especially the elderly, have different readings between arms. If the difference between the two readings remains more than 15mmHg on the second reading, measure subsequent blood pressure in the arm with higher readings for subsequent measurements.

If the difference is greater than 10mmhg for diastolic and 15mmHg for systolic on three readings, the patient should be referred for further evaluation. There is recent evidence that suggests a small difference in arm blood pressure is associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular events. Heart rate should also be recorded, as resting heart rate is another predictor of CVD fatal events.

In patients with different symptoms of postural hypotension, including postural dizziness or falls, if they have type 2 diabetes and are 80 years or older, firstly measure their blood pressure seated and allow the patient to stand for at least one minute then repeat a seated measurement.

Risk factors

Hypertension increases the risk of CVD. Evidence also suggests that high blood pressure can predispose people to the development of cognitive impairment, dementia, kidney damage, eye damage and sexual dysfunction.

Lifestyle risk factors for CVD (modifiable)

- Smoking — makes the blood thicker, therefore causes clots inside the arteries and veins. If a smoker quits, it decreases cardiovascular risk close to the risk of a person who has never smoked.

- Physical Inactivity — the WHO believes that 60 per cent of the world is not active. There is evidence that doing more than two hours and 30 minutes of moderate physical exercise weekly, ie, brisk walking or an hour of vigorous physical activity every day, can reduce the risk of CVD by 30 per cent.

- Obesity — There are 400 million people worldwide who are obese and one billion who are overweight. Obesity leads to hypertension, atherosclerosis, diabetes, etc, which puts one at a greater risk of CVD.

- High fat and sodium diet — A diet high in saturated fat is estimated to cause 31 per cent of coronary heart disease and 11 per cent of strokes worldwide. Increased consumption of oily fish, fruit and vegetables can reduce this high risk. The WHO has estimated that 2.5 million deaths could be prevented every year if the consumption of salt was decreased to the recommended daily allowance.

- Alcohol — Over-consumption of alcohol can damage heart muscles and increase the risk of CVD. Women should consume no more than two standard units per day and no more than three per day in males.

If a person’s parents have suffered from CVD, it can increase their risk by 50 per cent

Non-modifiable risk factors

Non-modifiable risk factors are those that can’t be controlled.

- Age — The risk of stroke doubles after the age of 55.

- Gender — Men have a greater risk of CVD than pre-menopausal women. Once a woman is past menopause, the risk is the same as a man.

- Genetics — Family history of CVD is a high risk. If a person’s parents have suffered from CVD, it can increase their risk by 50 per cent.

- Diabetes — Two-to-four times more likely to get CVD than a person who does not have diabetes.

- ? Socioeconomic status — Being poor has an impact on stress, anxiety and depression, which increases the risk.

- Ethnicity — Those of African ancestry have a higher risk than any other ethnicity.

Calculating cardiovascular disease risk

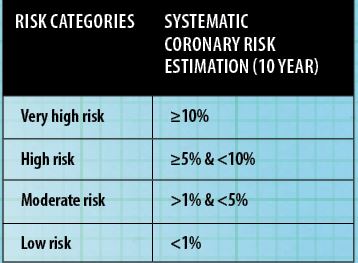

Systematic coronary risk estimation (SCORE) estimates the 10-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease, assists in making logical decisions and can help to avoid over-treatment and under-treatment. SCORE is estimated by investigating modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors a person may have. As shown in Figure 1, those at low-to-moderate risk may be given lifestyle advice to maintain, while high-risk persons may be candidates for lifestyle advice as well as drug treatments. If a person is in the very high-risk category, drug treatment is usually the required course of action.

That being said, people over the age of 60 should be interpreted more leniently, as age is a non-modifiable risk. CVD risk guidelines are available at the back of the BNF. A commonly used chart is the Joint British Societies Cardiovascular Disease Risk Prediction Chart. All adults over 40 and younger adults with a family history of premature CVD should have their CVD risk formally calculated.

Men are at a higher CVD risk than women because women’s risks are deferred for 10 years, not avoided. It is important to note that the CVD risk guidelines have only been validated on white Caucasians and therefore should be used in caution for other races. For example, patients from the Indian subcontinent will have a CVD risk of about 1.4 times that predicted by the charts. There is no need to use CVD risk charts for those with diabetes, as most people with diabetes will have a 10-year CVD risk of ?20%. The QRISK3 tool can be used to test CVD risk in people with type 2 diabetes and others under the age of 84. QRISK3 is a well-established calculator that estimates the risk for CVD in the next 10 years.

Diagnosis of hypertension

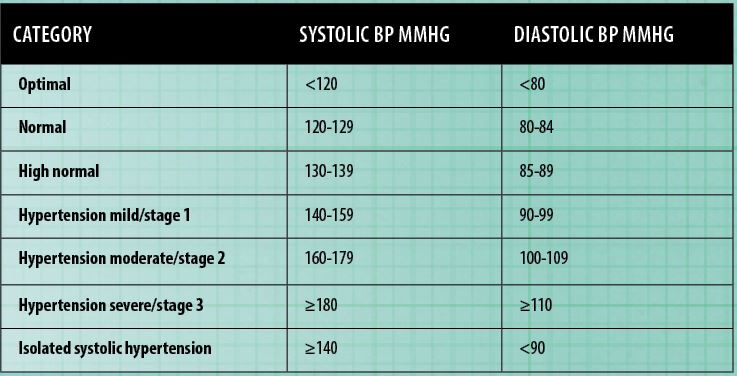

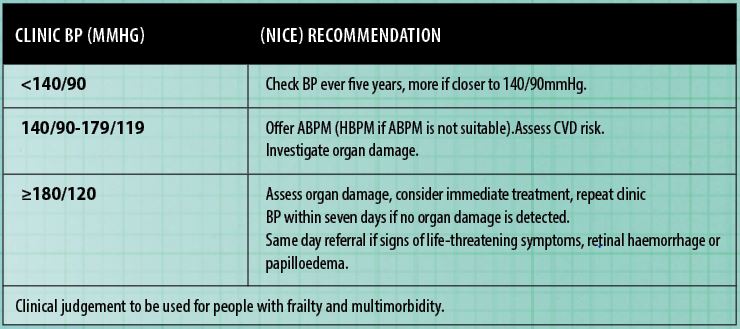

All adults should have their BP measured routinely every five years. Readings should be taken more frequently in those who have had high normal readings or higher in the past. The 2018 European Society of Hypertension – European Society of Cardiology classification of BP is outlined in Figure 2. A diagnosis of hypertension should be based on multiple clinic readings taken on separate occasions because blood pressure can vary throughout the day and can be raised by white coat and/or masked hypertension.

Research suggests that clinic systolic blood pressure (SBP) measurements can be 5-15mmHg higher than SBP levels obtained by ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABMP) and home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM). Therefore, ABMP and HBPM can give more accurate readings.

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM)

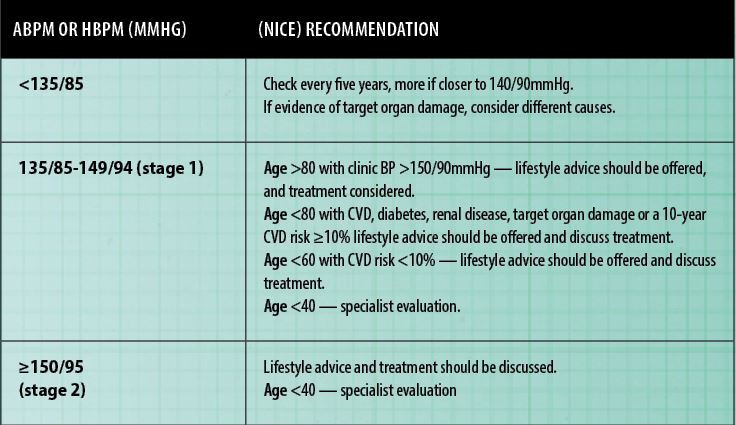

If a patient’s clinical blood pressure is between 140mmHg/90mmHg-180mmHg/90mmHg, ABPM may be offered. ABPM is better known as 24-hour BP monitoring. ABPM is the most preferred method of diagnosis because of its efficiency and accuracy.

- Make sure there are two measurements taken per waking hour, ie, 8am and 10pm.

- Use the mean value of 14 measurements throughout the person’s usual waking hours to ensure an accurate diagnosis of hypertension.

Home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM)

If ABPM is not suitable for a person, HBPM can be used instead as an alternative to diagnose hypertension.

- The person must record two consecutive readings one minute apart, while the person is seated.

- Record blood pressure morning and evening, for four-to-seven days.

- The measurements for the first day may be discarded and the mean of the other recorded days are used to confirm hypertension.

If a patient has severe hypertension (180/120mmHg or higher), immediate treatment must be considered, without waiting for ABPM and HBPM results. If there are no signs of target organ damage, a clinic blood pressure measurement must be carried out again within seven days. All hypertensive patients should have a thorough history and physical examination, assessing for evidence of target organ damage and potential causes of secondary hypertension. A formal CVD risk assessment must be carried out, ie, QRISK3. Routine investigations should include urinalysis (protein and blood), serum creatinine and electrolytes, blood glucose, serum total, haemoglobin, HDL cholesterol and a 12- lead ECG.

Treatment

The goal of treating hypertension is to achieve the maximum reduction in the risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Non-pharmacological measures which lower BP

Weight reduction, reduction of excessive alcohol intake (to <17 units/week for men and to <11 units/week for women), reduction of salt intake (to <5g/day ? 1 teaspoon), decrease caffeine consumption, decrease saturated and total fat intake, an increase in fruit and vegetable consumption and regular dynamic physical exercise all lower BP. Additional factors that reduce CVD risk include cessation of smoking, replacement of saturated fats with mono-unsaturated fats, and increased oily fish consumption. Effective implementation of these measures requires enthusiasm, knowledge, patience, and considerable time. It should also be backed-up with simple, clear, written information. If drug therapy is required, all these measures should be continued in parallel.

Pharmacological treatment

Studies have shown that antihypertensive treatment causes a significant reduction in mortality for cardiovascular events. The reduction in cardiovascular risk is relative to the fall in hypertension rather than the types of hypertensive drugs used. The reduction in cardiovascular risk is relative to the fall in hypertension rather than the types of hypertensive drugs used. Trials have shown that lowering blood pressure achieves a 35-to-40 per cent risk reduction for stroke, a 20-to-25 per cent reduction for myocardial infarction, and a 50 per cent reduction for heart failure.

When to initiate treatment?

Treat all those with sustained blood pressure of ?160/100mmHg. Treat all those with borderline blood pressures (Grade 1 hypertension) of 140-159mmHg systolic or 90-99mmHg diastolic if they also fall into one of the

following categories:

- Presence of cardiovascular disease.

- Presence of target organ damage, ie, kidney damage, heart failure, retinopathy (eye damage).

- Patient has diabetes.

Those with a greater than 20 per cent risk of having a cardiovascular event over the next 10 years, ie, ?5% risk of dying from CVD over the next 10 years.

Types of medication

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors: Reduce blood pressure by relaxing the blood vessels. Adverse effects include hypotension (may be profound after the first dose, especially in those with heart failure and renovascular disease), persistent dry cough (5-to-35 per cent), hyperkalaemia (caution with co-prescription with potassium-sparing diuretics or NSAIDs), and angio-oedema (condition that causes swelling of face and tongue).

They are contraindicated in patients with renovascular disease and should be avoided in women of childbearing potential. ACE inhibitors may also be prescribed for heart failure, diabetic nephropathy and chronic renal failure. ACE inhibitors, for which there are generics available and can be given once-daily, include Ramipril and Lisinopril, making them very popular. The incidence of cough appears to be higher in women. It is a persistent dry cough which is worse when lying down and generally doesn’t start for 24 hours after starting an ACE inhibitor.

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs): There are two types, the longer-acting dihydropyridine CCBs (nifedipine (modified release), amlodipine), and non-dihydropyridine agents (diltiazem, verapamil). Side-effects of the dihydropyridine CCBs include peripheral oedema, flushing and headache. The non-dihydropyridine CCBs should be avoided in patients with heart failure and used with caution in combination with beta-blockers. Amlodipine and lercanidipine are the most commonly used CCBs because they only need to be taken once daily and have fewer side-effects and interactions than non-dihydropyridine CCBs.

Thiazide diuretics: Anti-hypertensive effect is gradual in onset and persists for up to 24 hours. Erectile dysfunction (reversible on discontinuation) is a side-effect in men. High doses cause potassium levels to fall (hypokalaemia), uric acid levels to rise (increasing risk of gout), glucose levels to rise, leading to risk of diabetes (particularly in combination with a beta blocker), and lipids such as cholesterol to rise. High doses have no advantage in blood pressure control and should not be used.

Diuretics should be avoided in patients on lithium therapy and those suffering from gout. Thiazides can also be prescribed for heart failure. Higher doses are generally used to treat heart failure; therefore, stronger loop diuretics such as furosemide are more often used for heart failure. Hypokalaemia is rarely seen with thiazide diuretics, as the dose used for hypertension is low and they are often given in combination with drugs that increase potassium, ie, ACE inhibitors or angiotensin 2 inhibitors. However, careful monitoring of patients taking digoxin is required due to the risks of digoxin toxicity if hypokalaemia occurs.

To gain maximum benefits from a diuretic, sodium restriction is advised, ie, reduced salt in diet (less than 6g per day). Studies have shown that low-dose thiazides reduce most morbidity and mortality outcomes in patients with moderate-to-severe hypertension.

Angiotensin II receptor inhibitors (ARBs): They have similar indications, efficacy, cautions and side-effects as ACE inhibitors, but have a reduced incidence of cough and angio-oedema due to the lack of an effect on the kinin system. They are a popular alternative to ACE inhibitors as they don’t cause a cough. As with ACE inhibitors, ARBs may be prescribed for heart failure and diabetic nephropathy.

Alpha-blockers: They are generally used in combination with other agents, particularly in patients with other problems such as prostatism (prostate problems that affect 40 per cent of older men), type 2 diabetes and high cholesterol. They have modest lipid profile benefits (ie, reduce total cholesterol, LDL, total triglycerides and increase in HDL). Short-acting agents are associated with postural hypotension and are best avoided in patients with heart failure, ie, doxazosin, alfuzosin.

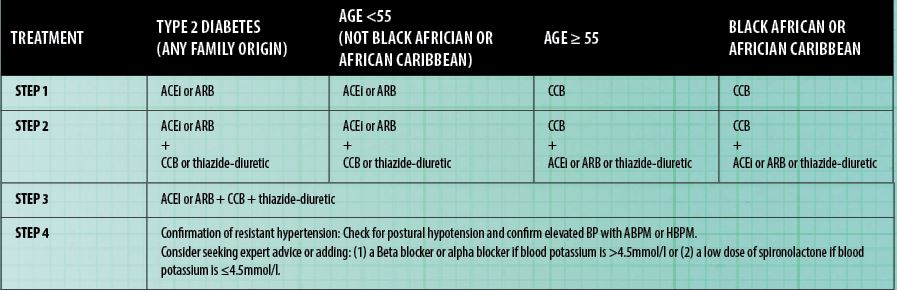

Beta blockers: NICE has stated that beta-blockers should no longer be routine first-line agents in hypertension. This decision is based on the evidence that the most used beta-blockers at usual doses carries high risk of provoking type 2 diabetes. Beta blockers also are less effective in older or black African patients.

However, beta blockers can still be considered in the treatment of hypertension in cases which include younger patients, particularly those who cannot tolerate ACE inhibitors and angiotensin 11 inhibitors, women of childbearing age and patients with an increased sympathetic drive. Some patients have a compelling reason for using beta blockers, ie, angina, myocardial infarction and heart failure. The above guidelines are not intended to be strictly adhered to; they are intended to give prescribers some guidance.

Adverse effects include lethargy, bradycardia (slow heart beat), cold hands and feet, worsening of symptoms of peripheral vascular disease and Raynaud’s syndrome, CNS effects such as impaired concentration and memory, vivid dreams (these are less frequent with the water-soluble beta-blockers such as atenolol and sotalol), aches in limbs, fatigue during exercise and metabolic effects (increased triglycerides, reduced HDL cholesterol). They are contraindicated in asthma.

Direct renin inhibitor: Aliskiren (Rasilez) was launched in the last 15 years. It works on the renin-angiotensin system in a slightly different way from ACE inhibitors and ARBs. A Drug and Therapeutics bulletin concluded that there is no evidence to justify replacing an ARB or ABE with aliskiren in patients with kidney disease, diabetes or heart failure. Other studies indicate its benefits do not outweigh the risks of taking aliskiren.

Aldosterone antagonists: Block the hormone aldosterone, which can cause fluid and salt retention, which in turn contributes to high blood pressure. They can increase potassium levels, which can cause muscle weakness, a low heart rate and fatigue. Other side-effects include dizziness, dry mouth, skin rash and stomach upset. These medications are usually used in conjunction with other drugs. They are prescribed in Step 4 (Figure 5) of treatment, ie, spironolactone and eplerenone.

Centrally-acting agents: Methyldopa can be used during pregnancy; it is otherwise rarely used as it is poorly tolerated. Methyldopa causes dizziness, drowsiness, headache, dry mouth, stuffy nose, confusion and depression.

Other vasodilators: Hydralazine, minoxidil and sodium nitroprusside all directly relax smooth muscle and can rapidly reduce BP. Should be reserved for use under hospital supervision to treat hypertensive crisis.

Choosing medication

The choice of agent is determined by many factors, which include:

- The cardiovascular risk profile of the patient.

- The presence of other conditions, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, renal disease and benign prostatic hypertrophy.

- The patient’s previous response to anti-hypertensive drugs (favourable or unfavourable).

- The cost of drugs.

- Interactions with medication the patient is taking for other conditions.

- If a woman is of childbearing age, is considering pregnancy, pregnant or breastfeeding.

NICE has (Hypertension in Adults: Diagnosis and Management, 2019) created an updated summary of the previous work on recommended treatment by the BIHS (formerly BHS), as seen in Figure 5 below.

According to MHRA drug safety updates, ACE inhibitors and angiotensin-II receptor antagonists (ARB) are not recommended for women planning pregnancy. When choosing an antihypertensive medication for black African or African-Caribbean adults, consider an angiotensin-II receptor antagonist (ARB), in preference to an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor.

Blood pressure targets with treatment

Blood pressure must be reduced and maintained at the following targets:

- Age <80 years — Clinical BP <140/90mmHg & ABPM/HBPM <135/85mmHg.

- Age ?80 years — Clinical BP <150/90mmHg & ABPM/HBPM <145/85mmHg.

- Pregnant — Clinical BP 135/85mmHg.

Interactions of OTC medications with hypertensive drugs

NSAIDs

Ibuprofen is probably the most clinically significant OTC interaction with anti-hypertensive agents. Ibuprofen (and all other NSAIDs) can increase systolic blood pressure by as much as 5-10mmHg due to fluid and salt retention. Paracetamol-based analgesics are safer in hypertensive patients.

Decongestants

Pseudoephedrine and phenylephrine (ie, Sudafed, Actifed) are best avoided in hypertensive patients as they cause a short-term increase in blood pressure.

Antacids

Some antacids such as Gaviscon have high sodium content and if used on a regular basis, can cause fluid retentions and reduce the effects of antihypertensive drugs. Low-sodium antacids such as Maalox are a better alternative for hypertensive patients. Bear in mind that Maalox does not have the same alginate protective coating effect on the oesophagus as alginate-based antacids like Gaviscon; it’s about balancing benefits and risks.

Special patient groups

Elderly

Hypertension becomes more common with age. More than 60 per cent of overall cases of hypertension are prevalent in people over the age of 60. As our world population ages, the increase of sedentary lifestyles leads to higher body weight and therefore the rise of hypertension. Studies have estimated that there will be a 15-to-20 per cent worldwide increase of reported hypertension by 2025, reaching 1.5 billion cases. Isolated systolic hypertension (ISH) is mostly prevalent in people over 50; it is caused by arteriosclerosis and fatty deposits on walls of arterial blood vessels. ISH is evident in 60-to-75 per cent of cases of hypertension in elderly people.

It includes the rising of SBP, while DBP stays the same or even declines. Elderly patients should be advised about the modifiable measures. Most elderly people with hypertension need drug therapy. Studies include that monotherapy only met blood pressure targets in 40-to-50 per cent of cases, so drug combinations are often required. The addition of one or two other hypertension medications have proven to reduce the side-effects of the first one. Initiation of therapy should be gradual, especially in frail individuals.

The HYVET study in 2008 showed that older patients with hypertension will benefit from hypertensive therapy much more than younger patients because of a greater absolute risk. The HYVET study showed a significant reduction in deaths in elderly patients using anti-hypertensive drugs. Thiazide diuretics and the dihydropyridine CCBs are particularly effective in older patients and in those with ISH.

Ibuprofen is probably the most clinically significant OTC interaction with anti-hypertensive agents

Diabetes

The co-existence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus (either type 1/2) substantially increases the risk of complications, including stroke, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure and peripheral vascular disease and increases cardiovascular mortality. For example, type 2 diabetics have a two-to-four fold higher risk of developing coronary heart disease and CVD accounts for 65-to-75 per cent of deaths in people with diabetes. The development of hypertension may be due to the onset of diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetics. In both type 1 and 2, the threshold for starting treatment is BP ?140/90mmHg. Previously, the blood pressure treatment target for diabetics was <130/80mmHg if there were signs of kidney damage.

In 2019, NICE updated these recommendations, as there was no sufficient evidence to suggest that lower blood pressure targets for diabetics reduced the rate of CVD. Therefore, people with diabetes (with signs of kidney disease) now have the same blood pressure targets as people who do not have diabetes. Evidence supports the use of many drugs, particularly the ACE inhibitors or ARBs. Maintaining normal BP with the use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs reduces the rate of decline in renal function. NICE advises that the first-line antihypertensive drug for type 2 diabetes should be a once-daily generic ACE inhibitor, ie, Lisinopril, Ramipril or an ARB, ie, Losartan or Irbesartan.

Pregnancy

Women may have pregnancy-induced hypertension, ie, hypertension which develops after the 20th week of pregnancy. The most worrying form of hypertension in pregnancy is pre-eclampsia, a potentially life-threatening condition. Rest remains the integral part of the management of hypertension in pregnancy. Most anti-hypertensive drugs are contraindicated in pregnancy. ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II inhibitors are particularly teratogenic, so must be avoided.

The first treatment for pre-eclampsia is labetalol. If labetalol is not suitable, nifedipine is recommended and if labetalol and nifedipine are not suitable, methyldopa is recommended. The best choice is based on pre-existing treatment, side-effects, foetal risks and the woman’s preference. A once-daily dose is more suitable for a pregnant person. Aspirin 75-150mg once daily can be offered from 12 weeks for a woman with chronic hypertension. NICE 2019 has stated that the blood pressure target for a pregnant woman is 135/85mmHg. l

References on request

Disclaimer: Brands mentioned in this article are meant as examples only and not meant as preference to other brands. Written by Eamonn Brady (Pharmacist), Whelehans Pharmacies, 38 Pearse St and Clonmore, Mullingar. Tel 04493 34591 (Pearse St) or 04493 10266 (Clonmore). www.whelehans.ie.