Dr Donna Cosgrove MPSI PhD looks at the health benefits for infants of receiving the best nutrition possible in early life

Introduction

Although every child has the right to good nutrition according to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, under-nutrition is associated with 2.7 million child deaths (45 per cent) annually. Worldwide in 2018, 149 million children aged under five years were stunted (too short for age), 49 million were estimated to be wasted (too thin for height), and 40 million were overweight or obese.1 The first two years of a child’s life are particularly important: Research has shown that adequate nutrition during this time decreases morbidity and mortality, reduces the risk of chronic disease, and contributes to optimal development. Many infants and children do not receive optimal feeding; for example, only about 36 per cent of infants aged 0–6 months worldwide were exclusively breastfed over the period of 2007-2014.

Breastfeeding

Breast milk, as the sole source of nutrition for infants in the first six months of life, plays a critical role in development. WHO and UNICEF recommend:1

? Early initiation of breastfeeding (within one hour of birth).

? Exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life.

? Introduction of nutritionally adequate and safe solid foods at six months, together with continued breastfeeding up to two years of age or beyond.

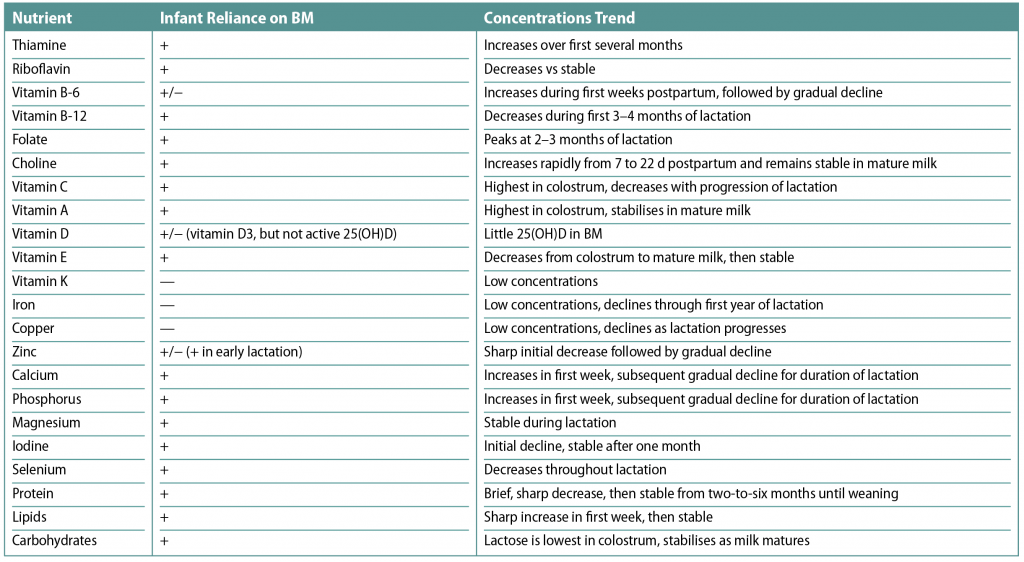

Between the ages of six and 12 months, breast milk can provide about half of a child’s energy needs, and between 12 and 24 months, about one-third of energy needs. At around six months, additional foods are required. If additional foods are not introduced (or if given inappropriately), then growth may be delayed.1 Infants of mothers with adequate nutrition have reserves of some nutrients at birth, but they depend entirely on breast milk for other nutrients. Table 1 shows the nutrients present in breast milk.2

The HSE has an ‘Ask the expert — Breastfeeding’ online advice section, where queries on the topic can be submitted. These receive a reply within 24 hours, or else there is an option to chat online during certain times.3

Benefits of breastfeeding

Breastfeeding improves IQ, school attendance, reduces the risk of overweight and obesity, and is associated with higher income in adult life.1 An important benefit is protection against infections — this is observed in both developing and industrialised countries. Breastfeeding reduces rates of gastrointestinal infections; necrotising enterocolitis; respiratory infections and otitis media; sudden infant death syndrome; atopic diseases; coeliac disease; inflammatory bowel disease; diabetes mellitus; and leukaemia. In some cases, it is reasonably clear that such benefits are specific to the milk itself, rather than the act of breastfeeding.5 Longer durations of breastfeeding also reduce the risk of ovarian and breast cancer in the mother.

Human breast milk contains many compounds, including living cells, hormones, active enzymes, immunoglobulins, and a variety of bioactive compounds. Considering this, concentrations and types of nutrients in infant formulas cannot always match exactly those in human milk. Some nutrients in human milk vary from the beginning to the end of each feed, between the stages of lactation, and as a result of different maternal diets.5

The actual contribution of these variations to the nutrition provided by human milk, however, has not been completely studied to determine their specific roles in affecting nutritional outcomes. In contrast, new ingredients that are added to infant formulas must be shown to be safe and to provide important clinical benefits based on extensive and carefully-conducted clinical trials.

In clinical practice, comparisons between human milk and infant formula feeding are difficult to determine — intake volumes and exact composition of the feed cannot be known precisely. While randomised, controlled trials are the most scientific method, it is not possible to conduct an RCT comparing human milk-fed and formula-fed infants due to potential ethical issues.

Infant formula can be a suitable alternative to breast milk in the first 12 months of a baby’s life.4 Research into the benefits of breastfeeding is still needed, however, in order to determine which factors in human milk compared to the act of breastfeeding itself are most important for producing the beneficial effects on infant growth, body composition, and neurodevelopmental outcomes.5 Skin-to-skin contact, even without breastfeeding or human milk feeding, may be helpful to establish a healthy microbiome in the infant. Identifying the way the breast-fed infant is held, how often, and for how long at each feeding may provide important clues for how bottle-feeding techniques might be adapted to more closely mimic what is beneficial for the breast-fed infant. It may be the case that holding and feeding by the father or other carers may provide the same benefits for the bottle-fed infant that have been noted in the breast-fed infant. When these questions are addressed, this may help parents improve feeding skills and determine what specifically is beneficial to breastfeeding, since many human milk-fed infants are fed expressed milk by bottle or infant formula by the bottle.

If the infant is breastfed or taking less than 300mls of infant formula a day, 5 micrograms of vitamin D3 should be given every day from birth to 12 months. If the baby is fed more than this, they do not need a supplement.3 This is because there has been an increase in the amount of vitamin D added to infant formula (due to a change in EU law as of February 2020).

Weaning

Infants develop at different stages, so solids should be introduced when they are ready — usually at around six months. A premature baby (born before 37 weeks) should be introduced to foods other than milk sometime between ‘corrected age’, four and six months.3 A small amount of food should be tried to begin with, and increased gradually as the child gets older, along with gradually introducing variety in food and texture.1 The number of times that the child is fed could be increased from, ie, two-to-three meals per day for infants aged six-to-eight months of age to three-to-four meals per day for infants nine-to-23 months of age (with one-to-two additional snacks as required). Babies should not be given solid foods before 17 weeks (four months) because:3

? Their kidneys are not mature enough to handle food and drinks other than milk.

? Their digestive systems are not yet developed enough to cope with solid foods.

? Breast milk or formula milk is enough to meet nutritional needs until six months old.

? Introducing other foods or fluids can displace the essential nutrients supplied by breast or formula milk.

? Introducing solids too early can increase the risk of obesity in later life.

? It can increase their risk of allergy.

Waiting until after 26 weeks (six months) is not recommended because:

? The infant’s energy needs can no longer be met by either breast milk or formula milk alone.

? Iron stores from birth are used up by six months and their iron needs can no longer be met by milk alone.

? It delays their opportunity to learn important skills, ie, self-feeding.

? Introducing different textures stimulates the development of muscles involved in speech.

Shop-made baby food is available for convenience, but home-made baby foods are cheaper to prepare, and it may be preferable to know exactly what the baby is eating because the person preparing the food has control over the ingredients in the meals. It also introduces the baby to tastes and textures of family foods. The HSE website provides a step-by-step guide to making baby food at home.3

Different fruits and vegetables contain different vitamins and minerals, so the more types an infant tries, the better. Starchy foods, ie, bread, cereals, potatoes, rice, couscous, and pasta provide energy, nutrients and some fibre, although giving wholegrain foods to children aged under two is not recommended. These foods may make them full before they have ingested the calories and nutrients needed. Whole cows’ milk, which can be given from the age of one, and full-fat dairy products are a good source of calcium and contain vitamin A. As young children need the energy provided by fat, skimmed or low-fat milk is not generally recommended for those under five years old.

However, when an infant is over two, lower-fat dairy products can gradually be introduced. Protein and iron are important for growth and development: Beans, pulses, fish, eggs, foods made from pulses (such as tofu, hummus and soya mince) and meat are excellent sources of protein and iron.

Infants develop at different stages, so solids should be introduced when they are ready, usually at around six months

Iron comes either from: 1) meat and fish, which are easily absorbed by the body; or 2) plant foods, which are not as easily absorbed. If a child doesn’t eat meat or fish, enough iron can be ingested from iron-rich foods such as fortified breakfast cereals, dark green vegetables, broad beans and lentils. Water or whole milk is the best drink to offer an infant. Diluted fruit juice (one-part juice to 10 parts water) can be served with meals, which helps reduce the risk of tooth decay. From age five, undiluted fruit juice or smoothies can be served with a meal.4

By the time a child is five, they can eat a healthy, balanced diet like the one recommended for adults.

Introducing different flavours and textures

To determine how pre- and postnatal flavour experiences affect liking of flavours at weaning in infants, a randomised clinical trial was performed in which pregnant women were randomised to groups that differed in whether and when they drank carrot juice.6

Infants who experienced the flavour of carrots in either amniotic fluid or mother’s milk were more likely to eat carrot-flavoured cereal than control infants. Similarly, when mothers ate fruits or vegetables, infants experienced the flavours in amniotic fluid and then mother’s milk, which increased the palatability of these foods for the infant. Learning about foods through dietary transmitted flavours in amniotic fluid and mother’s milk may be an important feature of dietary learning — there is some evidence that dietary learning is more pronounced during early life. Research has also shown that repeated dietary exposure to a fruit or vegetable increases the likelihood of the infant eating it.

Another approach is to offer a variety of flavours: Infants who were repeatedly exposed to different vegetables on alternate days ate more of not only the vegetables to which they were exposed, but also novel vegetables. Children can continue to learn to like foods, but it is more difficult as they grow older, potentially because they can more so refuse to taste these foods and cannot learn to like them. Sometimes letting a child help to prepare food can encourage them to eat what they’ve made.3

References on request.