Dr Donna Cosgrove PhD MPSI looks at the risk factors and mechanisms of disease in inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome, including treatment of symptoms and an overview of clinical research data

Microbes in Gut Health

The brain interacts with the gut through the gut-brain axis (GBA). Disturbances in this and in the microbial landscape in the intestine contribute to the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).1 In normal circumstances, bacteria in the GI tract mainly consists of firmicutes (64 per cent), bacteroidetes (23 per cent), proteobacteria (8 per cent), and actinobacteria (3 per cent), and are important for priming the immune system, breakdown of dietary substrates inaccessible to host enzymes, and detoxification of xenobiotics.1,2

‘Dysbiosis’ is the term given to the disturbance of gut microbiota. Gut viruses have also been identified, primarily Podoviridae, Siphoviridae and Myoviridae. The GI microbial flora cohabits through a relationship of symbiosis, or ‘commensalisms’. It is believed that the microbiota in an infant is derived from its mother’s microbes during vaginal delivery or Caesarean section.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

IBS has an estimated prevalence of 10-to-15 per cent worldwide and in some populations is more common in women than in men (ie, North America), though not all.3,5 IBS is based on symptoms and is defined by the presence of abdominal pain or discomfort, with altered bowel habits. It is diagnosed when the symptoms are not attributable to any alternative disorder being present, with the onset often occurring during adolescence. Women more commonly report IBS with abdominal pain and constipation (IBS-C) whereas men more so report diarrhoea (IBS-D)-type symptoms. The predominant subtype experienced by an individual can change over time, as well as symptom severity: It is a chronic relapsing disease.3

The main symptoms of IBS are:

? Abdominal cramping.

? Loose/frequent stools.

? Constipation.

? Bloating.

? Discomfort or pain.

? Flatulence.

Symptoms can be brought on by food intake/specific food sensitivities. Other symptoms include mucus in stools, lack of energy, nausea, backache, urinary symptoms, and incontinence.3 Importantly, IBS shows comorbidity with psychiatric disorders such as anxiety, depression and somatoform disorders, which can profoundly impact on quality of life.

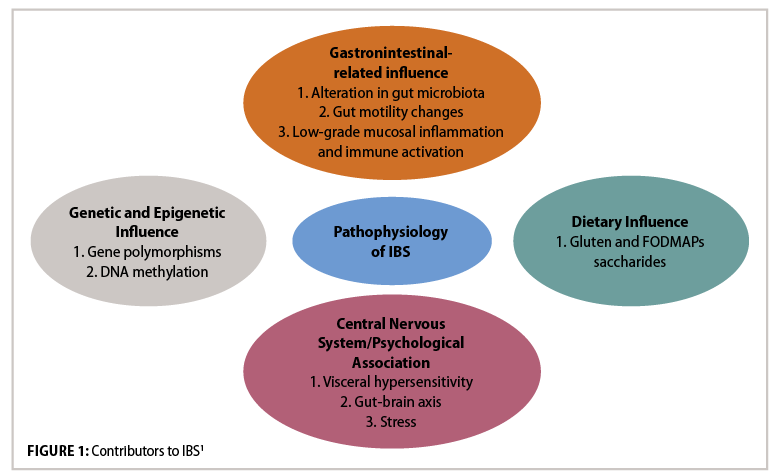

IBS Aetiology

Dysfunction of the innate immune system contributes to low-grade inflammation in IBS.1 In IBS patients, activation of the immune system in the colonic mucosa is observed, along with infiltration of immune cells and release of inflammatory cytokines (particularly IL-6, TNF-a, and IL-1b), although the cause for this is unclear. In healthy individuals, the mucus epithelium barrier in the GIT means that microbes are confined to the intestinal lumen, and immune responses maintain barrier integrity. However, once the barrier is damaged by an influx of inflammatory mediators, this causes an alteration in the intestinal environment and changes the gut microbiota composition. This alteration of gut integrity and immunity may contribute to IBS. Combination of this low-grade mucosal inflammation with visceral hypersensitivity and impaired bowel motility leads to IBS. Visceral hypersensitivity (increased pain sensation in the bowel due to physiological stimuli) is a large factor: Patients with visceral hypersensitivity tend to have lower colonic distension pain threshold, and a normal stimulus will intensify pain. The prevalence of this hypersensitivity in IBS patients can vary from 33-to-90 per cent, occurring more frequently in IBS-D patients. The cause of this hypersensitivity is due to multiple factors, including dysbiosis, brain-gut communication, diet, psychological factors, genetics, inflammation, immunological factors and altered intestinal permeability.

IBS Treatment

Identifying the patient’s predominant bowel complaint helps guide treatment choice. Subtyping IBS by Predominant Stool Pattern can help with this:

1. IBS with constipation — hard or lumpy stools ?25%; loose or watery stools <25% of bowel movements.

2. IBS with diarrhoea — loose or watery stools ?25%; hard or lumpy stools <25% of bowel movements.

3. Mixed IBS — hard or lumpy stools ?25%; loose or watery stools ?25% of bowel movements.3

Management interventions for IBS include pharmacological treatments (ie, antispasmodics, antidiarrheal, low-dose antidepressants, probiotics, etc), modifications in lifestyle and dietary changes.4

Pharmacological Therapies

Loperamide is specifically useful in IBS-D because it reduces stool frequency, increases stool consistency, and can be used prophylactically.

Antispasmodics can be useful in IBS when there is an exaggerated gastrocolonic reflex. This is partially cholinergically mediated. Hyoscine has an antispasmodic effect useful in these cases. Peppermint oil is also an antispasmodic, with calcium channel-blocking properties.

Diet is very important in IBS as food and breakdown products can affect gut physiology. Ingestion of FODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols) are easily fermentable by gut bacteria into methane and hydrogen gasses, and are associated with bloating and abdominal pain in about 70 per cent of patients, regardless of IBS subtype.1 FODMAPs may cause GI distension and stimulate abnormal intestinal motility due to osmotic increase in fluid volumes and are found in foods such as wheat, onions, some fruits and vegetables, sorbitol, and some dairy, among others.

Soluble fibre like ispaghula can improve symptoms, unlike insoluble fibre like wheat bran, which contains FODMAPs. NICE guidance recommends limiting the intake of insoluble fibres and starch, with ispaghula powder (a soluble fibre) or foods high in soluble fibre being encouraged, particularly for IBS-C.1

Osmotic laxatives such as lactulose can be useful in IBS-C as it pulls water back into the bowel to soften the stool. However, they do not reliably improve pain or bloating.

Antidepressants work in multiple ways to help symptoms: They affect pain perception, mood and motility. Serotonin plays a role in GIT motility, and altered levels are found in patients with IBS.1 Most trials so far have not separated out the subtype of IBS patients recruited, so recommendation by IBS subtype is not possible. However, because TCAs prolong gut transit times, whereas SSRIs decrease transit time, it may be the case that TCAs would be more effective in IBS-D, and SSRIs of greater benefit in IBS-C, although this has not yet been investigated.5 Some of the strongest evidence for the pain-modifying effects of antidepressants in chronic painful disorders comes from studies looking at serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) duloxetine and milnacipran, but neither of these have been tested in IBS trials to date.

Psychological therapies appear to be effective for the treatment of IBS. These therapies modify cognitive, behavioural, and emotional responses to symptoms. This results in a reduction in IBS symptoms, improved quality of life and, with CBT in particular, enabling patients to target maladaptive thoughts and behaviours that exacerbate or maintain these symptoms.

Exercise encourages regular bowel movements. People with IBS should be encouraged to increase their physical activity, even by as little as a 20-minute walk every day.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

IBD refers to ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), both relapsing and remitting diseases characterised by chronic GIT inflammation.6 The prevalence of IBD is between 5-and-20 per cent and it is more common in women and younger people. UC affects mainly the rectum (95 per cent) and colon, but CD can affect any part of the tract from the mouth to the anus. IBD affects all age groups but there are two main peaks of onset: Between the ages of 25-to-35, and between the age of 60 and 80.6,8

Symptoms of IBD include:

? Diarrhoea.

? Abdominal pain.

? Tenderness.

? Weight loss.

In UC, blood is more likely to be present, with a feeling of rectal urgency or tenesmus. The mucosal and submucosal layers of the colon are affected. As CD is a transmural disease, occurring across the entire wall of the organ, this leads to complications like intra-abdominal abscesses, fistulas, linear clefts and strictures, in turn causing intestinal obstruction.

IBD Aetiology

The full mechanism behind IBD development is still unclear, however genetic factors and environmental factors both contribute, stimulating a sustained abnormal immune response that results in disruption of the intestinal mucosa. Some 235 genetic regions have been associated with IBD susceptibility. Less-diverse microbiota profiles have been demonstrated in UC patient samples.2

IBD Treatment

The extent, location and severity of the disease determine the treatment approach.3 In acute IBD, the goal of treatment is to treat the symptoms and induce clinical remission while improving quality of life. Afterwards, treatment is tailored to maintain this.7

Aminosalicylates are more effective in UC than in CD. Mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid) delivers anti-inflammatory effects in the GIT or rectal delivery. The aminosalicylate sulfasalazine is made up of mesalazine coupled to a sulfapyridine and is broken down by colonic bacteria when administered orally. This leads to mesalazine delivery within the large intestine, although sulfapyridine is associated with side-effects. Drugs that do not contain sulfapyridine are available, ie, olsalazine (a molecule in which mesalazine is bonded to a second mesalazine).

Corticosteroids are potent anti-inflammatories. Prednisolone, hydrocortisone, and methylprednisolone are useful to achieve remission in acute IBD, especially where aminosalicylate therapy has failed. These are not useful in relapse prevention or for long-term use due to side-effects (bone disease, diabetes, infection risk). The corticosteroid budesonide is better tolerated than conventional steroids and is effective at inducing remission in both UC and CD.7

Immunosuppressants, including the thiopurines (azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine), are used for both UC and CD. These drugs are not useful for inducing remission as their full effect can take up to six months. However, these drugs are associated with serious adverse effects (ie, pancreatitis, allergic reaction, infection, bone marrow suppression). Methotrexate can be used in CD maintenance therapy as an alternative to azathioprine, although it has its own side-effects.

Biologics — TNF blockers and leucocyte adhesion inhibitors: Drugs that inhibit the effects of TNF-?, ie, infliximab, are reserved for moderate-to-severe IBD refractory to other therapies. People treated with biologic agents may over time experience a loss of efficacy, thought to be due to the development of antibodies to the drug. Adalimumab, certolizumab, and golimumab are alternatives for patients who cannot tolerate, or have become resistant to, infliximab. Natalizumab reduces inflammation through inhibiting the adhesion of alpha-4-beta-7 integrin to the receptors on endothelial gut cells.

For inducing remission in UC, NICE guidance recommends initial use of aminosalicylates. For treating CD, NICE guidelines recommend monotherapy with a conventional corticosteroid to induce remission.9 More specific guidance for additional circumstances and monitoring (ie, for neutropaenia) is recommended in the NICE guidelines.

Antibiotics are known to influence several disorders, including IBD, by modulating the host microbiota. Antibiotics can potentially ameliorate the microbial environment of patients with IBD both by decreasing proinflammatory bacteria and by increasing beneficial ones.2 Several antimicrobial drugs have been investigated in patients with UC for the induction and/or maintenance of disease remission, ie, ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, tobramycin and rifaximin, to varying degrees of success. Currently, there is no firm evidence to support a routine role for antibiotics in IBD.

Probiotics have been investigated in IBD and IBS, with the aim of reversing dysbiosis.2 However, a Cochrane review of many studies showed that probiotics were not more effective than placebo or active comparators in inducing the remission of active UC. When only a subset of studies (the randomised controlled trials only) were pooled, probiotics were shown to be effective in the induction of remission (RR 1.80). In rare cases, probiotics have also been shown to cause sepsis in patients with UC, therefore they should be used with caution, particularly in severe disease. Only limited data are available for probiotic application in CD, however, none of them have shown efficacy. Synbiotics refer to the combination of probiotics. In theory, these should be more potent than the probiotic or prebiotic components used on their own.1 Another medical treatment, faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), involves the administration of faecal microbiota into the intestinal tract of a recipient. This therapeutic approach was practiced in ancient China since the 4th Century. The physician Ge Hong suggested to patients with severe diarrhoea to use fresh stool as a choice of treatment. More recent studies indicate that FMT appears to be a moderately effective treatment for patients with active UC. Further study of more targeted, specific probiotics and synbiotics in IBD and IBS is needed, along with refinement of some other treatments.