Erectile dysfunction is a common issue in men, particularly older men with comorbidities

Erectile dysfunction (ED), the inability to achieve or maintain an erection for satisfactory sexual performance, affects a considerable proportion of men at least occasionally and can have a substantial negative impact on quality of life.1 It is estimated that at least 150 million men globally have ED. It is difficult to obtain accurate values for the true prevalence of ED however, as many patients fail to seek medical attention, and many clinicians are reluctant to ask patients about their sexual health.

ED is generally treatable, however, if left untreated, ED can be a source of severe emotional stress for both the man and their partner. ED can be a symptom of a wide range of underlying pathologies, and is often an under-recognised but important cardiovascular risk factor.1 Owing to its strong association with metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease, cardiac assessment is warranted in men with symptoms of ED.2

Aetiology

Although most men will experience periodic episodes of ED, it tends to become more frequent with advancing age. Many factors can contribute to sexual dysfunction in older men, including physical and psychological conditions, comorbidities and polypharmacy. Aspects of an ageing man’s lifestyle behaviour and androgen deficiency, most often decreasing testosterone levels, can affect sexual function.1,6 Studies have shown that the percentage of men who engage in some form of sexual activity decreases from 73 per cent in men aged 57–64 years, to 26 per cent for men aged 75–85 years. The aetiology for this decline in male sexual activity is multifactorial, and is in part related to female partners’ menopause at approximately 52 years of age, leading to a significant decline in female libido and desire to engage in sexual activity.7

While ED is associated with ageing, many studies and large-scale surveys have concluded that ED is also a major health concern among young men.11,12,13

In the past, erectile dysfunction was almost always considered a psychogenic disorder

One study in 2013 reported that one- in-four men seeking medical help for erectile dysfunction in the real-life setting is <40 years of age.11 Another study in 2016 concluded that 22.1 per cent of men aged under 40 years of age had low (<21) Sexual Health Inventory for Men (SHIM) scores.13

In the past, erectile dysfunction was almost always considered a psychogenic disorder. However, evidence now suggests that more than 80 per cent of cases have an organic aetiology.2 While most patients with ED have organic disease, some do have a primary psychological cause, particularly younger men. Even when ED is organic in nature, there are almost always psychological consequences regarding relationship issues, cultural norms and expectations, loss of self-esteem, shame, and anxiety and depression related to sexual performance.1

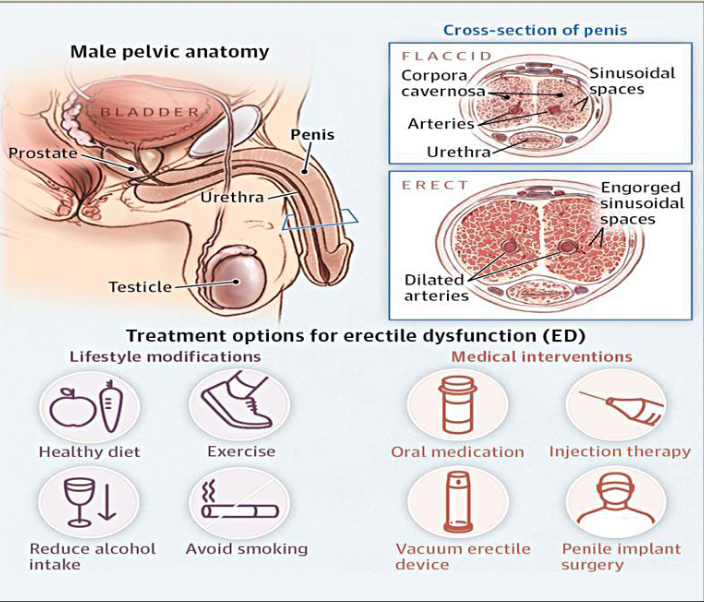

ED is multidimensional in nature, and can be broadly divided into endocrine and nonendocrine causes. The condition can be caused by any disease process which affects penile arteries, nerves, hormone levels, smooth muscle tissue, corporal endothelium, or tunica albuginea. It is closely related

to cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia, hypertension, and endothelial dysfunction. ED and vascular disease are thought to be linked at the level of the endothelium. Endothelial dysfunction results in the inability of smooth muscle cells lining the arterioles to relax and prevents vasodilatation.3 The endothelial cell is known to affect vascular tone and impact the process of atherosclerosis and impact ED, CVD and peripheral vascular disease.6

Cardiovascular disease and hypertension are very significant risk factors for erectile dysfunction. CVD causes a narrowing and hardening of the arteries, leading to reduced blood flow to the corporal bodies, which is essential for achieving an erection.6 Both cardiovascular disease and ED involve endothelial cell dysfunction in their pathophysiology. Besides cardiovascular disease, there are strong correlations between ED and hyperlipidaemia, diabetes, hypogonadism, obesity, smoking, alcoholism, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) with lower urinary symptoms (LUTS), depression, and premature ejaculation.1

Diabetes is a common aetiology of sexual dysfunction, because it can affect both the blood vessels and the nerves that supply the penis. Men with diabetes are four times more likely to experience ED, and on average experience it 15 years earlier than men without diabetes. Obesity is also correlated to the development of several types of dysfunction, including a decrease in sex drive and an increase in episodes of ED.6

Neurogenic ED is caused by a deficit in nerve signalling to the corpora cavernosa. Such deficits can be secondary to spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, lumbar disc disease, traumatic brain injury, radical pelvic surgery and diabetes.2

Men being treated for prostate cancer with treatments such as radical prostatectomy, radiation therapy or the use of luteinising hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists and antagonists often experience ED.6

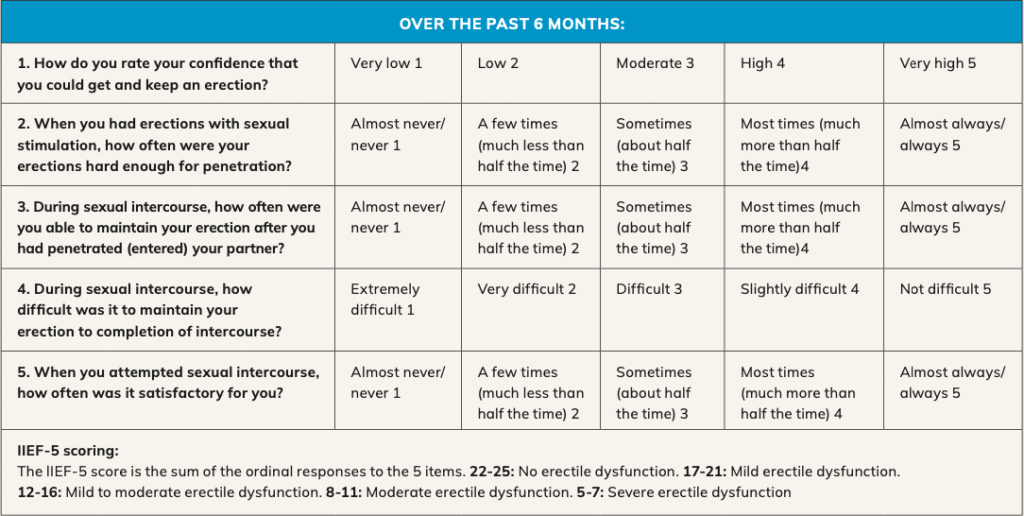

Figure 1: Sexual Health Inventory for Men (SHIM).5 Source: https://www.urologypartners.co.uk/repository/originals/The_International_Index_of_Erectile_Function.pdf

The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) Questionnaire4,5

The IIEF is a multidimensional validated questionnaire with 15 questions in the five domains of sexual function (erectile and orgasmic functions, sexual desire, satisfaction with intercourse and overall sexual satisfaction), and there is also an abbreviated format of five questions in the Sexual Health Inventory for Men (SHIM).5 The severity of ED is described as mild, moderate or severe, according to IIEF-5 questionnaire, with a score of 1–7 indicating severe, 8–11 moderate, 12–16 mild–moderate, 17–21 mild, and 22–25 no erectile dysfunction.2, 4

Investigations and diagnosis

A thorough medical history, detailed sexual history, and physical examination are required before commencing treatment or further investigations. It is important to distinguish between psychological and organic causes of ED, as well as to ensure that the patient has ED and not another disorder. History

that points towards a psychological aetiology includes sudden onset of ED, especially if it is related to a new partner or a major life-changing event, situational ED, normal erections with masturbation or a different partner, presence of morning erections, and high daily variability in erectile rigidity.1, 6

The main differential diagnosis for ED is hypogonadism, loss of libido, depression with low mood, and other psychological conditions. It may also be the first manifestation of diabetes or CVD as well as depression. It is important to differentiate between true ED and other sexual disorders such as premature ejaculation, and this is usually assessed by obtaining a good sexual history.1, 2

A complete medication list including supplements should be checked with the patient. Numerous medications are listed with ED and/ or a decreased libido as a side- effect. Antidepressants, particularly the SSRIs such as citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine and sertraline, can contribute to ED.6 Prescription drugs that can cause ED include hydrochlorothiazide, cimetidine, ketoconazole, spironolactone, sympathetic blockers, thiazide diuretics, and other antihypertensives. ACE inhibitors and calcium channel blockers are the least likely to cause ED. Beta-blockers are only a minor contributor, while alpha-blockers can improve erectile function.1,2

Vascular risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes and lifestyle factors such as smoking, activity level, alcohol intake, and the use of any recreational drugs should be assessed.1 A full general and cardiovascular examination should be undertaken, as ED can be the first symptom of underlying vascular disease. Peripheral pulses should be checked and blood pressure measured. The genitalia should be carefully inspected for hypogonadism, signs of infection, the presence of penile fibrosis or plaques, and phimosis. Hair distribution, breast size (gynaecomastia), and a detailed neurological examination

are important. The cremasteric reflex should be evaluated. A normal reflex is retraction or elevation of the ipsilateral testicle. This reflex will be normal if the thoracolumbar erection centre is intact.1,2

Investigative blood tests include a full blood count, electrolytes, renal and liver function tests, HbA1c to screen for diabetes mellitus, and a lipid profile. Testosterone levels are checked and a morning testosterone level is recommended, especially if there are symptoms suggestive of hypogonadism such as loss of sexual desire or testicular atrophy on physical examination. Thyroid function (TSH) may also be measured. Other blood tests can include LH and prolactin if hypogonadism is found, and sickle cell in the African/Caribbean patients.1,2

Treatment and management

Initial treatment for ED is based on lifestyle modification followed by first-line therapies using PDE5 inhibitors and vacuum erection devices (VEDs). Second-line therapies consist of an intraurethral suppository (IUS) of prostaglandin E1 (alprostadil) and intracavernosal injection (ICI) with vasoactive substances. Surgical intervention is usually reserved as the final option after conservative options have been discussed or attempted.6

The role of testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) as a potential to improve erectile function in ED remains an issue for clinicians who are comfortable treating androgen deficiency. Androgens are known to have a significant impact on the function of the smooth musculature within the corpus spongiosum. Testosterone supplementation is more effective as a treatment for low libido than for ED. For most men with both ED and hypogonadism, oral PDE5 inhibitors alone are recommended as the initial therapy. Testosterone supplementation is reasonable in men with proven hypogonadism and ED who have already failed PDE5 inhibitor therapy or who also have low libido. Hypogonadal patients with borderline erectile rigidity are most likely to benefit from testosterone supplementation.1

TRT may cause increased levels of haemoglobin or haematocrit, which is associated with an increased risk of heart attack, stroke and blood clots, and can also cause an enlarged prostate or other prostate disorders. During TRT treatment, the prostate specific antigen (PSA) will be measured to monitor for any changes and this is particularly important in men over 45 years of age.8 As a result of using testosterone replacement, natural production of testosterone may be reduced. This may lead to a reduction in sperm production and fertility. Other side-effects of TRT include weight gain, increased appetite, hot flushes, acne, depression, restlessness, irritability, aggression, tiredness, general weakness and excessive sweating.8

Lifestyle modifications are considered first-line therapy for ED, and men should be encouraged to make the necessary changes to benefit both their sexual function and their overall health. Recommended lifestyle modifications include increased physical activity, improved diet, stopping smoking, drugs, and alcohol, and good control of diabetes, lipids, and cholesterol. The patient’s

PDE5 inhibitors improve erectile quality for most men, and work by enhancing blood flow in the corpora cavernosa

medication history should be carefully reviewed to remove or alter the doses of any medications which may be contributing to ED. Men who have a psychological cause should be offered psychosexual counselling.1,6

PDE5 inhibitors improve erectile quality for most men, and work by enhancing blood flow in the corpora cavernosa. These medications such as sildenafil are generally used on demand, and need to be taken about an hour before sexual intimacy. Tadalafil is a longer-acting daily preparation medication, therefore eliminating the ‘on-demand’ need. It is important for men to be aware that PDE5 inhibitors do not initiate the erectile response. Sexual stimulation is required to release nitric oxide from the vascular endothelium and penile nerve endings to commence the erectile process. PDE5 inhibitors are highly effective and have an overall success rate of up to 76 per cent.1 They are contraindicated in patients taking nitrates, but otherwise are safe and effective. When PDE5 inhibitors are co- administered with nitrates, pronounced systemic vasodilation and severe hypotension can occur.6 PDE5 inhibitors and -adrenergic receptor blockers, often used for treatment of BPH, need to be taken at least four hours apart.2

Among second-line therapies, external vacuum devices (VCDs) are a good, non-surgical option for patients with ED. VCDs are clear plastic chambers placed over the penis, tightened against the lower abdomen with a mechanism to create a vacuum inside the chamber. This directs blood into the penis. If an adequate erection occurs inside the chamber, the patient slips a small constriction band off the end of the VCD and onto the base of the penis. An erection beyond 30 minutes is not recommended.

While cumbersome, these devices are considered safe.6 Practice with the device improves outcomes and some degree of manual dexterity is required. VCD devices are the most inexpensive long-term therapy for ED, and a non-invasive option for patients who deem it acceptable. While the efficacy rates of VCD devices are high, patient satisfaction rates are lower. 1

Other second-line therapy includes the use of either intracavernosal injections (ICI) or intraurethral suppositories (IUS). A small needle is used to inject the ICI medication into the lateral aspect of the penis through a small-gauge needle. These vasoactive agents include prostaglandin E1, papaverine and phentolamine and sometimes atropine, which work alone or in combination to elicit an erection. Response is dose-related, usually occurs within 10–15 minutes, and does not require stimulation. A concern with ICI use is priapism, and if this occurs the patient will need to seek urgent medical attention. Bruising can also occur, due to it being an injected medication. The intraurethral suppository consists of a tiny pellet of prostaglandin E1 inserted into the urethral meatus. Response is dose-related, and onset usually occurs within 10– 15 minutes. Patients need to be trained on the technique of the IUS before use, and should be advised that pain or burning may occur with this medication. 2, 6

In men who fail to respond to first- or second-line therapy, or who are not interested in conservative therapies, penile prosthesis implantation is available. Penile implants include malleable and inflatable devices, although most implants used are of the inflatable variety. Adverse effects including malfunction and infection are rare, and patient satisfaction is high.6

Outlook and future therapies for ED

Clinical studies in gene therapy are looking towards replacing proteins that may not be functioning properly in the penile tissue of men with ED. Replacement of these proteins may result in improvement in ED, as has already been demonstrated in animal models given experimental gene therapy. Human studies may demonstrate success with this therapy in the future.6

Stem cell studies may also provide advancements in the treatment of ED in the future. The mechanism of action of stem cells is to generate angiogenesis with subsequent increase in cavernosal smooth muscle cells within the corporal bodies.9

The clinical studies published to date provide encouraging results, with improvement of sexual function reported with no side-effects. Although pioneering, stem cell studies to date are small-scale, with a short follow-up period, various aetiologies of ED and without a control group.1

Melanocortin activators are drugs that act through the central nervous system, and have been shown

in animal studies to produce an erection. Initial studies in humans suggest that the drug PT-141 can be effective if given intranasally in men with psychological rather than physical causes, and mild-to- moderate ED. Larger studies are necessary, however, to demonstrate the safety and overall effectiveness of these drugs.9

Another potential new treatment for ED is penile low-intensity shock wave lithotripsy. This consists of 1,500 shocks twice a week for three-to-six weeks. The purpose is to stimulate neovascularisation to the corporal bodies with improvement in penile blood flow and endothelial function. The use of low-intensity shock wave lithotripsy may convert PDE5 inhibitor non-responders to responders.1

Author: Theresa Lowry-Lehnen, RGN, GPN, RNP, BSc, MSc, M. Ed, PhD, Clinical Nurse Specialist and Associate Lecturer at South East Technological University

References

1. Leslie S, Sooriyamoorthy T. (2022). Erectile Dysfunction. Stat- Pearls Publishing 2022 Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ books/NBK562253/.

2. Yafi FA, Jenkins L, Albersen M, Corona G, Isidori AM, Goldfarb S, et al. (2016). Erectile dysfunction. Nature Reviews. Disease primers, 2, 16003. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.3

3. Kaya C, Uslu Z, Karaman I. Is endothelial function impaired in erectile dysfunction patients?

Int J Impot Res. 2006 Jan- Feb;18(1):55-60. doi: 10.1038/ sj.ijir.3901371.

4. International Index of Erectile Dysfunction Questionnaire. Available at: www.urologypart- ners.co.uk/repository/originals/The_International_Index_of_Erec- tile_Function.pdf.

5. Science Direct (2017). Inter- national Index of Erectile Func- tion. Available at: https://www. sciencedirect.com/topics/medi- cine-and-dentistry/internation- al-index-of-erectile-function

6. Mobley DF, Khera M, Baum N. Recent advances in the treatment of erectile dysfunction. Postgrad Med J. 2017 Nov;93(1105):679- 685. doi: 10.1136/postgrad- medj-2016-134073.

7. Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O’Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007 Aug 23;357(8):762-74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423.

8. NHS Kings College (2021). Tes- tosterone Replacement Therapy. Information for Patients. Available at: https://www.kch.nhs.uk/Doc/ pl%20-%20934.1%20-%20tes- tosterone%20replacement%20 therapy.pdf.

9. Khera M, Albersen, M, Mulhall J. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for the treatment of erectile dysfunc- tion. J Sex Med 2015; 12:1105–6. doi:10.1111/jsm.12871.

10. Frey A, Sønksen J, Fode M. Low-intensity extracorporeal shockwave therapy in the treat- ment of postprostatectomy erectile dysfunction: a pilot study. Scand J Urol 2016; 50:1–5. doi:10.3109/216 81805.2015.1100675.

11. Capogrosso P, Colicchia M, Ven- timiglia E, Castagna G, Clementi MC, Suardi N, et al. One patient out of four with newly diagnosed erectile dysfunction is a young man–worrisome picture from the everyday clinical practice. J Sex Med. 2013 Jul;10(7):1833-41. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12179.

12. Heruti R, Shochat T, Te- kes-Manova D, Ashkenazi I, Justo D. Prevalence of erectile dysfunc- tion among young adults: results of a large-scale survey. J Sex Med. 2004; 1:284–291.

13. Papagiannopoulos D, Khare N, Nehra A. Evaluation of young men with organic erectile dysfunction. Asian J Androl. 2015; 17:11–16. 14. Najari B, Kashanian J. Erectile Dysfunction. JAMA. 2016;316(17):1838. doi:10.1001/ jama.2016.12284.