Donna Cosgrove MPSI provides an overview of some of the issues commonly encountered in conception

Introduction

Conception is the process of becoming pregnant, involving fertilisation and implantation. Fertility is the capacity to establish a clinical pregnancy, and infertility refers to when clinical pregnancy has not been established after 12 months of regular, unprotected sexual intercourse. Sub-fertility, a term often used interchangeably with infertility, is any form or grade of reduced fertility in couples unsuccessfully trying to conceive. The severity of subfertility is determined by the time it takes to become pregnant:

- 80 per cent of pregnancies occur in the first six cycles during which there is regular intercourse around the fertile ovulation time window;

- A further 10 per cent of couples will conceive in the next six cycles;

- About half of the remaining 10 per cent will conceive within two years;

- The remaining 5 per cent will have difficulty becoming spontaneously pregnant.1

Over 186 million people worldwide experience infertility, an estimated 8-12 per cent of reproductive-aged couples. Primary infertility is diagnosed when a woman has never been pregnant, and secondary infertility refers to a woman who has previously been pregnant but is unable to establish another pregnancy. The same categorisation can be applied to males in terms of participation in the initiation of a pregnancy. Secondary infertility is the most common type of female infertility globally, and is more common in areas with high rates of unsafe abortion or poor maternity care which leads to infections. Males are solely responsible for 20-30 per cent of infertility cases, but contribute to 50 per cent.

Fertility rates

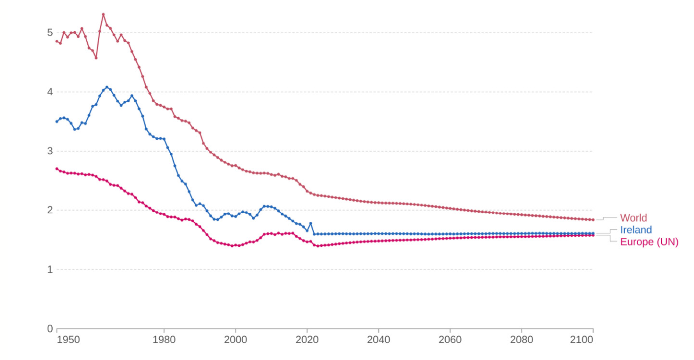

The rates of fertility in each country are affected by its social structure, religious beliefs, economic prosperity, and urbanisation.2 Figure 1 shows fertility rates3 from 1950 onwards for the world, Europe, and Ireland specifically (there is information on more regions available from United Nations data). Replacement fertility is the level at which each generation exactly replaces the previous one (ie, two births per woman), meaning no population growth or decline. Two thirds of the countries in the world now have birth rates below the replacement rate.

Figure 1: Fertility rate (children per woman) 1950 to 2100.3 Data source: UN, World Population Prospects (2024). The total fertility rate is the number of children that would be born to a woman if she were to live to the end of her child-bearing years and give birth to children at the current age-specific fertility rates

Infertility

The drop in fertility rate has many contributing factors such as the availability of contraception and a host of social and economic aspects, but there is also a range of physical and hormonal factors that may cause fertility problems among people who wish to conceive.4 Ovulatory dysfunction is the most common cause of female infertility.5 A range of hormonal factors can disrupt the complex sequence of events that result in ovulation. Hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis dysfunction is responsible for about 85 per cent of cases.

Ovulatory disorders include those caused by problems with the hypothalamus or pituitary, which leads to hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. This is when insufficient sex hormone is produced by the ovaries (or testes in men), and is responsible for 10 per cent of anovulation cases. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common cause of anovulatory infertility, which can interfere with the process at multiple points. PCOS is characterised by irregular menstrual cycles, anovulatory bleeding, hyperandrogenism, and metabolic issues like hyperinsulinemia. Hyperandrogenism is due to an imbalance between androgen and FSH/LH levels.

Infertility in women can also be due to:4,5

- Ovarian insufficiency or failure suggesting premature depletion of oocytes due to genetic, acquired, or unknown causes is another cause of ovulatory disorders eg, Turner syndrome;

- Scarring from pelvic or cervical surgery;

- Issues with cervical mucus (and facilitating sperm migration);

- Fibroids (may prevent implantation or block a fallopian tube);

- Pelvic inflammatory disease (infection of the upper female genital tract) often caused by an STI;

- Medicines (NSAIDs, chemotherapy, antipsychotics, spironolactone, illegal drugs).

Infertility in men can be due to:4

- Semen problems (lack of sperm, sperm that are not moving properly, abnormal sperm);

- Testicular issues (infection, cancer, surgery, congenital defects, undescended testicles, injury);

- Ejaculation disorders;

- Medicines (sulfasalazine, anabolic steroids, chemotherapy, herbal remedies).

For about one in four couples with fertility problems, no cause is ever established.

Conception

The strongest predictor of fertility is a woman’s age at conception, but additional factors like lifestyle and environmental factors play an increasing role.

- Regular sexual intercourse increases the chances of pregnancy;6 ie, every two or three days, without contraception, especially around ovulation (12 to 16 days before menstruation);

- Maintaining a healthy weight: An elevated (>27 kg/m2) or low BMI (<17 kg/m2) is linked with ovulatory dysfunction. In women with an elevated BMI, subfertility is related to metabolic changes such as hyperinsulinemia and associated androgen excess;7

- Increased intensity and duration of exercise can affect female infertility, but does not appear to affect male fertility;

- Stopping alcohol consumption. Moderate alcohol intake (<2 drinks/day) probably has no or minimal effects on fertility, but any more should be avoided. Abstinence is recommended for the female partner;6,7

- Stopping smoking (for both men and women). Tobacco use by the female partner, and possibly the male partner, has been associated with subfertility;

- Reducing stress levels can increase fertility.

Women trying to conceive (TTC) should take a folic acid supplement every day until 12 weeks pregnant to reduce the risk of a neural tube defect ie, when the foetus’s spinal cord does not form in a normal way. A higher 5mg dose is advised in some patient groups. If a couple have been TTC for over a year without success, they should speak to their GP (or sooner if over 36).

Increased intensity and duration of exercise can affect female infertility, but does not appear to affect male fertility

Hormones and conception

When a female baby is born, each ovary contains one to two million primordial follicles, within which the immature eggs are arrested (in prophase 1 of meiosis) until the onset of puberty. With each menstrual cycle, the average ovary loses 1,000 follicles through the selection of the dominant follicle that is eventually released. This follicle loss also accelerates with age. Tight hormonal regulation is required for successful development and release of an egg.7

The primary hormones involved in conception are:

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which is secreted by the hypothalamus, leads to the release of FSH and LH from the anterior pituitary gland, depending on GnRH pulse frequency. At higher GnRH pulse frequencies, LH secretion increases disproportionately more than FSH secretion. At lower GnRH pulse frequencies, FSH secretion is favoured.

- Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) stimulates the maturation of immature oocytes before ovulation. Each follicle has the potential to release an egg for fertilisation.

- Luteinising hormone (LH) induces egg release (ovulation) and preparation for implantation. The LH surge increases the activity of proteolytic enzymes that weaken the ovarian wall, allowing release of the oocyte. Once released, the follicular remnants produce progesterone. Home ovulation tests measure LH in the urine to detect the LH surge prior to ovulation.

- The steroid hormone oestrogen governs the growth and regulation of the female reproductive system and secondary sex characteristics. When oestrogen levels reach a critical level during the cycle, secreted by maturing oocytes in the ovary in preparation for ovulation, this causes an LH surge.

- The steroid hormone progesterone prepares the endometrium for implantation of the fertilised egg and maintenance of pregnancy. If pregnancy occurs, the corpus luteum maintains the early pregnancy until the placenta develops sufficiently to take over progesterone production.

Ovulation, regulated by levels of FSH and LH, is defined by the rupture of the dominant follicle in the ovary, which releases an egg into the abdominal cavity. If the HPA ovarian axis is well regulated, ovulation occurs about 14 days prior to menstruation in each cycle. The egg has the potential to be fertilised once taken up by the fimbriae of the fallopian tube.

Follicular release is preceded by the follicular phase, in which the follicle develops. During the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, oestrogen production rises as a result of hormonally active granulosa cells inside the follicle. Once these levels reach a critical point and remain high for two days, this leads to an increase in GnRH secretion, causing an LH surge and egg release.

This is followed by the luteal phase which lasts from days 14 to 28, beginning with the formation of the corpus luteum and ending in implantation and pregnancy or luteolysis (corpus luteum destruction) and endometrial shedding. The remains of the mature follicle, post egg release, are stimulated by FSH and LH to become the corpus luteum. The progesterone-secreting corpus luteum makes the endometrium more receptive to implantation. The reduced hormone levels stimulate the release of FSH again to start follicle stimulation for the next cycle. If an egg is fertilised, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is produced by the developing placenta in order to preserve the corpus luteum, maintaining adequate progesterone levels until the placenta can take over.

Most pregnancy tests can be performed from the first day of a missed period, or at least 21 days after unprotected sex.6 These tests look for the presence of hCG which is produced around six days after fertilisation. False negative results can occur; however, if a test is positive, it is unlikely to be a false positive.

Assisted conception

The most common fertility treatments currently available are:8

- Ovulation induction (OII): Medications are used to stimulate the development of one or more mature follicles in the ovaries. Ultrasound/blood tests are used to monitor follicular development;

- Intrauterine insemination (IUI): Healthy sperm are collected and inserted directly into the uterus at the time of ovulation;

- In vitro fertilisation (IVF): A woman’s eggs are fertilised by sperm in a laboratory, where they develop into embryos. The embryos are transferred back to the uterus a few days later;

- IVF with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI): Sperm is injected directly into an egg to assist contraception. The embryos are then transferred back to the womb;

- Donor-assisted human reproduction is another option.

Since September 2023, free assisted human reproduction services (IUI, IVF, and ICSI) have been accessible through the HSE.

References

- Vander Borght M and Wyns C (2018). Fertility and infertility: Definition and epidemiology. Clinical Biochemistry, 62, 2-10.

- Nargund G (2009). Declining birth rate in developed countries: A radical policy re-think is required. Facts, views and vision in ObGyn, 1(3), 191.

- Ritchie H and Rodés-Guirao L (2024). Peak global population and other key findings from the 2024 UN World Population Prospects. OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved 5 September 2024 from https://ourworldindata.org/un-population-2024-revision.

- National Health Service. (2023). Infertility in women. Retrieved 5 September 2024 from www.nhs.uk/conditions/infertility/causes/.

- Hornstein MD, Gibbons WE, and Schenken RS (2022). Natural fertility and impact of lifestyle factors. Retrieved 5 September 2024 from www.uptodate.com/contents/natural-fertility-and-impact-of-lifestyle-factors?search=conception&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1 per cent7E150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1.

- National Health Service. (2022). How long does it usually take to get pregnant? Retrieved 5 September 2024 from www.nhs.uk/pregnancy/trying-for-a-baby/how-long-it-takes-to-get-pregnant/.

- Holesh JE, Bass AN, and Lord M (2017). Physiology, ovulation. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441996.

- Citizens Information (2024). Fertility treatments and assisted human reproduction in Ireland. Retrieved 5 September 2024 from www.citizensinformation.ie/en/birth-family-relationships/before-your-baby-is-born/fertility-treatments-and-dahr/.