Donna Cosgrove MPSI says pharmacists can be a great source of advice when you want to know how to best maintain and rebalance a healthy digestive system

The digestive system is made up of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT), which is a series of hollow organs: the mouth, oesophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and anus. The liver, pancreas, and gallbladder are the solid organs of the digestive system. The small intestine is made of the duodenum, jejunum, and the ileum at the end. The large intestine includes the appendix, caecum, colon, and rectum. The digestive organs break food into smaller parts using motion (chewing, squeezing and mixing) and digestive juices (stomach acid, bile, enzymes). In addition to the organs of the GIT, there are other important factors that impact digestive health including bacteria, the nervous system and hormones 1.

Upper GI issues include 2:

Chest pain

Chronic and recurrent abdominal pain

Dyspepsia

Dysphagia

Halitosis

Hiccups

Nausea and vomiting

Rumination

Lower GI complaints include:

Constipation

Diarrhoea

Gas and bloating

Abdominal pain

Rectal pain or bleeding

Some of these are ‘functional illness’, ie, no physiological cause found after evaluation.

The gut microbiome

The adult microbiome includes about 30 species of Bifidobacterium, 52 species of Lactobacillus, and others, such as Streptococcus and Enterococcus 3. Each region of the gut has a different microbiota composition. Metabolites released from the gut microbiome include vitamins (folate, biotin), short chain fatty acids (SCFAS; propionate, butyrate, acetate) and neuroactive metabolites (serotonin, gamma-butyric acid), among others. Gut microbiota have a significant influence on brain physiology and behaviour, and conversely, the microbiome is affected by stress exposure, suggesting a bidirectional communication at the brain-gut axis. Maintenance of, and if required, restoration of appropriate intestinal microbiota may prevent development of diseases including obesity, allergies, and GI disease.

Probiotics

Probiotics are defined as “live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host” 4. The most commonly used probiotics are non-pathogenic and able to withstand the harsh environment of the GIT, eg Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and yeasts such as Saccharomyces boulardii. Positive effects of probiotics are mediated through different mechanisms, including competition against pathogenic bacteria in their binding to intestinal epithelial cells, enhancement of intestinal epithelial barrier function, inhibition of the growth of pathogens through secretion of antimicrobial peptides, and/or enhancement of serum IgA production, among others 3. Much evidence for the positive effects of probiotics and GI, emotional and pain disorders come from animal studies, with further clinical trials needed in humans. Probiotics are beneficial in managing abdominal pain in certain cases, anxiety in some patient groups, H. pylori eradication, and ulcerative colitis, although the evidence is uncertain for Crohn’s Disease.

A newer term ‘pharmabiotics’ describes a broader group of bacteria and bacterial substances: live or dead microbes, microbial components, and microbe-produced substances. There has been interest in the use of genetically modified bacteria to deliver molecules of therapeutic interest at mucosal surfaces, eg anti-inflammatory cytokines, anti-pathogenic molecules, and potentially vaccines (also known as ‘immunobiotics’).

Although probiotics are commonly used, the evidence for their use in humans is at times unclear due to the level of heterogeneity in both the probiotics used in clinical trials, and the assessment of outcomes in these trials. However, research does suggest that probiotics have a beneficial impact on

Enhancing immune response

Balancing the colonic microbiota

Reduction of faecal enzymes implicated in cancer initiation

Treatment of diarrhoea associated with travelling and antibiotic therapy

Control of rotavirus and Clostridium difficile-induced colitis

Prevention of ulcers related to Helicobacter pylori

Prevention of IBD

Prevention of urogenital infection

Gastric ulcer treatment

Obesity management

Management of hypercholesterolaemia

Prevention of diabetes4, 5.

Prebiotics

Our modern western diet is much lower in nondigestible carbohydrates, or fibre, than all previous diets in human history, potentially contributing to increases in chronic lifestyle diseases 6. Prebiotics are a class of non-digestible foods that stimulate bacterial growth or activity in the GIT 3. Prebiotics are present in dietary food products including asparagus, sugar beet, garlic, chicory, onion, Jerusalem artichoke, wheat, honey, banana, barley, tomato, rye, soybean, cow’s milk, peas, and beans. The most common prebiotics include fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS), galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS), and trans-galacto-oligosaccharides (TOS). The effect of prebiotics in humans is dependent on degradation (fermentation) products from gut microbiota action. This is impacted by the structure of prebiotics and the type of microbiota present. Fermentation produces SCFAs, which have multiple effects including stimulation of the innate immune system against pathogenic microorganisms and reduction of colonic pH. Because SCFAs can diffuse into blood circulation through enterocytes, prebiotics can also affect distant organs 7, offering protective effects not only in the GI system, but also the central nervous system, immune system, and cardiovascular system.

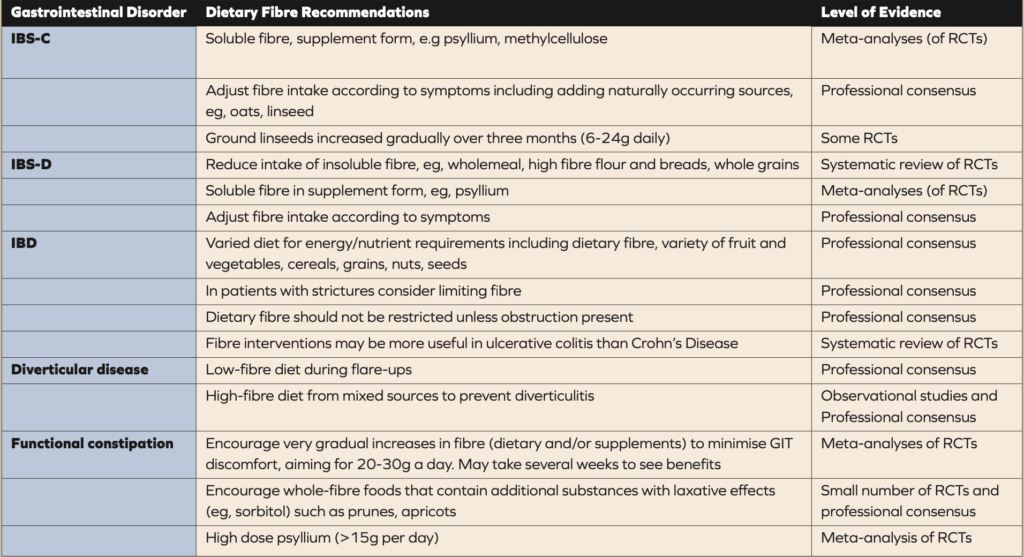

Table 1. Guidelines and recommendations for the use of fibre in gastrointestinal disorders (8). IBS-C, irritable bowel syndrome with constipation; IBS-D, irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea; RCTs, randomised controlled trials.

Fibre

Dietary fibre includes all carbohydrates that are neither digested or absorbed in the small intestine and have a degree of polymerization often or more monomeric units 8. A meta-analysis of epidemiological studies of fibre in disease prevention showed that for each increase in dietary fibre intake from food of 7g per day, there was a significantly reduced risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, colorectal cancer, rectal cancer and diabetes. A further meta-analysis showed that the greatest risk reduction is when dietary fibre intake from food is between 25g per day and 29g per day. However, the average intake of dietary fibre by adults worldwide is typically less than 20g per day.

The potential benefit of dietary fibre for digestive health is attributed to its effect on nutrient digestion and absorption, improving glycaemic and lipaemic responses, regulating plasma cholesterol through limiting bile salt resorption, influencing gut transit, and microbiota growth and metabolism. Some physicochemical characteristics, eg solubility, viscosity, and fermentability, determine fibre function in the GIT, including effects on micronutrient availability, gut transit time, stool formation and microbial specificity.

Assessing the impact of fibre on digestive health can be complicated due to the variations of fibre available. Studies examining the effect of fibre can include fibre made up of only one molecule type such as FOS, fibres extracted from naturally occurring plant sources like alginate or psyllium, or single foods with naturally occurring fibre (prunes or wholegrain cereals). Furthermore, synthetic or extracted fibres may have different physicochemical characteristics when consumed as part of a wholefood that might affect their functional properties, eg improved bioaccessibility. Fibre consumption as part of the whole food is also likely to provide additional beneficial nutrients like vitamins and polyphenols, so identifying the effect of fibre alone can be challenging. Food processing provides another level of complexity. Recommendations relating to dietary fibre and treatment of IBS, IBD, diverticular disease, and constipation are made in some guidelines, but the limited number of, and variation in, study interventions makes it difficult to make precise recommendations.

Animal studies indicate that both soluble (swells via water absorption) and non-soluble (bulking) fibre in the ileum may reduce GIT motility and secretion through mediators like glucagon-like peptide 1 and 2. Fibre viscosity may also play a part in regulatory effects of fibre consumption, including increased satiety in humans, and may also contribute to some cholesterol lowering capacity of some fibres (ie, beta-glucan). The solubility of fibre can influence the upper GIT through regulation of gastric emptying and nutrient absorption, although this attribute can be affected by individual gastric pH levels.

Emotional states and digestive health

In a study (24,000 participants) examining the link between stress/depression on the prevalence of digestive diseases, the incidence of functional dyspepsia (FD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) increased as stress level increased. Incidence of FD also increased with more severe levels of depression. Depression was also found to be an independent risk factor for certain types of gastric carcinoma. Whether these associations are due to indirect or direct effects is unclear: high stress levels or depression may impact lifestyle habits that lead to these issues rather than only impacting directly via the gut-brain axis. This association is probably derived from the gut-brain interaction. Corticotropin-releasing hormone (a significant mediator of the stress response in the brain-gut axis) can increase intestinal permeability. In addition, serotonin and the serotonin transporters can also be associated with brain-gut function in functional GI disorders 9. Authors suggest that the evaluation of the mental state may be useful to assess patients with GI symptoms.

Digestive health in pharmacy It is very common to occasionally experience digestive issues, and many temporary digestive symptoms can be treated with OTC products. Pharmacy staff can help with advice on maintaining and rebalancing a healthy digestive system while also promoting awareness of subtle signs that might be associated with more severe illness.