Eamonn Brady MPSI provides an overview of wound management, including the important role of pharmacists

Every community pharmacy in Ireland encounters patients seeking help for cuts, grazes, blisters, or minor burns. These are among the most frequent minor ailments presented at the pharmacy counter, and pharmacists are ideally placed to provide safe, evidence-based advice. With the accessibility of community pharmacies and their clinical expertise, pharmacists play a key frontline role in wound management, ensuring early intervention, appropriate product selection, and prompt referral when required.

Minor wounds and burns, while often simple to manage, can delay healing or lead to infection if not treated correctly. The key to effective management lies in early assessment, proper cleansing, maintaining a moist environment for healing, and preventing infection. Pharmacists can offer all of these within the community setting, bridging the gap between self-care and medical treatment.

With the growing demand on GP and emergency services, community pharmacists are increasingly recognised as the first port of call for wound- related concerns. Pharmacists often see wounds earlier than GPs or practice nurses, providing a unique opportunity to prevent complications. By applying clinical reasoning and evidence-based dressing selection, pharmacists can reduce unnecessary antibiotic use and improve healing outcomes.

The pharmacist’s role also extends beyond the advice on appropriate management and advice on dressings. Patients frequently seek reassurance about if a wound is healing normally, how often to change a dressing, or whether a wound “looks infected”. Providing clear, practical guidance builds public confidence in pharmacy services and reinforces the pharmacist’s role as a

The pharmacist’s role also extends beyond the advice on appropriate management and advice on dressings

trusted healthcare professional. In Ireland, many pharmacies are also involved in supplying dressings under the HSE Community Schemes or supporting nursing home residents, meaning pharmacists must be familiar with formulary-approved products, reimbursement protocols, and appropriate documentation. As wound care products continue to evolve, with innovations such as hydrogel, silver, and honey-based dressings now common in community practice, pharmacists must stay up to date with product efficacy and indications.

This article explores how pharmacists can manage minor wounds and superficial burns effectively within the community setting. It outlines evidence-based approaches to assessment, cleansing, dressing selection, infection prevention, and patient counselling, ensuring every pharmacy interaction contributes to safer, faster wound recovery and reduced complications.

1. Understanding wound types

Before recommending treatment or selecting a dressing, it is essential for pharmacists to accurately identify the type and severity of the wound. Even minor injuries vary greatly in how they should be managed, and recognising key differences helps guide safe, effective care.

Abrasions, or grazes, are superficial wounds where the top layer of skin (epidermis) is scraped away, which is commonly caused by falls or friction injuries. These wounds usually ooze slightly but rarely bleed heavily. The main priorities are cleansing to remove debris and protecting the area from infection. Lacerations, by contrast, are deeper cuts where the skin has been torn or sliced. While most small lacerations can be managed in the pharmacy with appropriate cleansing and dressing, those with gaping edges may need referral.

Blisters are a common presentation, particularly from friction, burns, or ill-fitting footwear. Pharmacists can advise patients not to intentionally burst blisters, as the overlying skin acts as a sterile barrier. If a blister has already ruptured, it should be cleansed gently and covered with sterile non-stick dressing to prevent infection. Hydrocolloid plasters (Compeed, Granuflex, Duoderm, and Tegaderm) are often ideal for small blisters, as they cushion the area and promote moist healing.

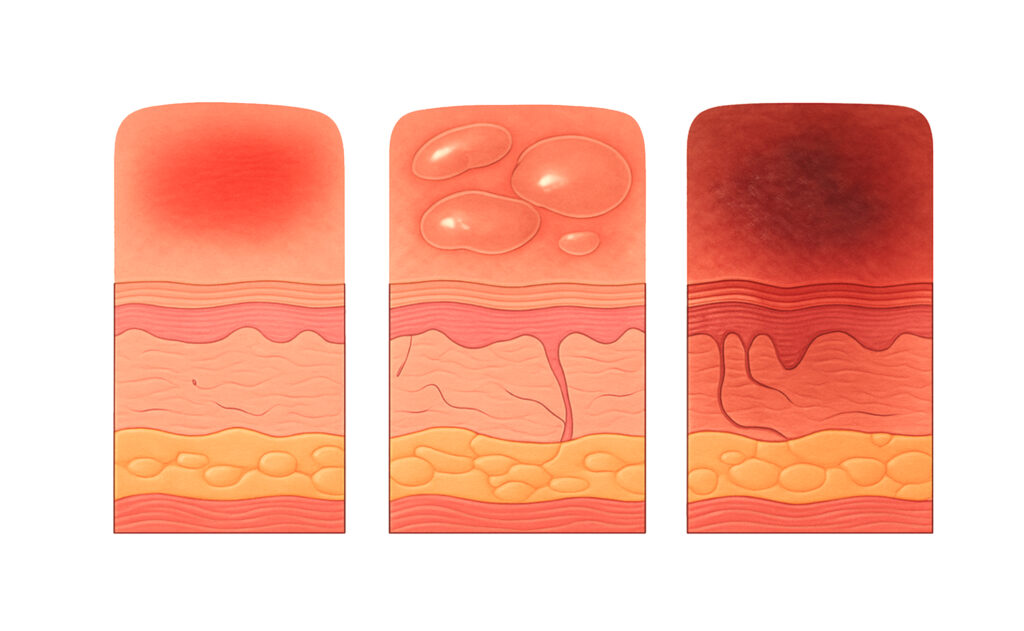

Minor thermal burns or scalds are frequent injuries, especially in households and workplaces. Pharmacists should be able to differentiate burn depth, as this determines the level of care and whether referral is necessary:

- Superficial burns (first-degree) involve only the epidermis, appearing red and painful without blistering.

- Superficial partial thickness burns (second-degree) affect the dermis and cause blistering and swelling.

- Deeper burns (deep partial or full thickness) are more serious, often painless due to nerve damage, and must be referred immediately.

Burns larger than 3cm in diameter, affecting the face, hands, feet, genitals, or joints, or occurring in children or older adults, should always be referred for medical review.

All wounds carry an infection risk, especially when contaminated or left uncovered. Pharmacists should educate patients on signs of infection which include increased redness, swelling, pus, pain,

or systemic symptoms such as fever. Referrals are warranted for non-healing wounds, extensive tissue damage, or wounds showing spreading redness (cellulitis). Early recognition and referral are key to preventing complications.

The dermis versus the epidermis

The dermis is the middle layer of the skin, the layer just beneath the surface (the epidermis). In simple terms, it is like the ‘engine room’ of the skin, where most of the important activity happens.

The dermis contains:

- Blood vessels, which bring nutrients and oxygen to keep your skin healthy;

- Nerves, which let you feel touch, pain, and temperature;

- Hair follicles, sweat glands, and oil glands, which help regulate temperature and protect your skin;

- Collagen and elastin fibres, which give your skin its strength and stretchiness.

So, while the top layer (epidermis) is what can be seen, the dermis is what keeps the skin strong, flexible, and alive underneath.

2. Cellulitis

Cellulitis is a skin infection that happens when bacteria get into a cut, scrape, or crack in the skin. It is characterised by the skin and the tissue underneath becoming red, swollen, warm, and painful. It often affects the legs but can happen anywhere on the body.

Typical signs include:

- Red, swollen skin that may spread quickly;

- Warmth and tenderness in the affected area;

- Pain or soreness;

- Sometimes fever or chills if the infection spreads.

If cellulitis is not treated, the infection can spread and become dangerous. The bacteria can move deeper into the skin and even reach the bloodstream. This may cause serious complications such as sepsis, which is a life-threatening infection that affects the whole body. Untreated cellulitis can also lead to abscesses, where pus collects under the skin, or long-term swelling called lymphoedema if the lymph system is damaged.

In very severe cases, parts of the infected tissue may die and need to be removed through surgery. Cellulitis can usually be cured easily with antibiotics when treated early but ignoring it can lead to severe ? and even life-threatening ? illness so it is important for pharmacists to be able to recognise cellulitis symptoms to advise quick referral.

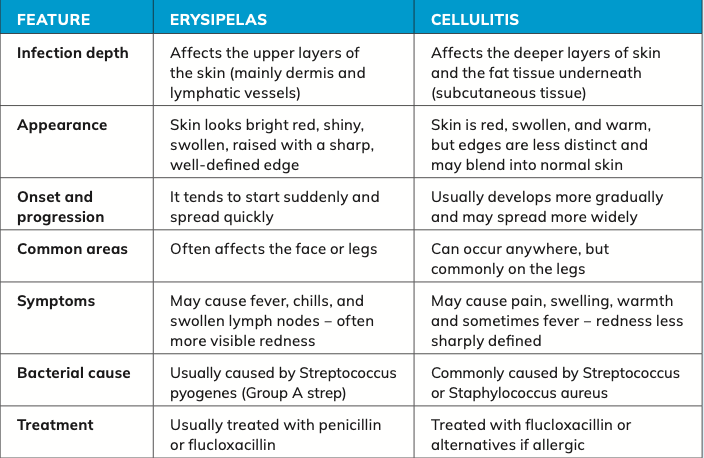

Difference between erysipelas and cellulitis Erysipelas and cellulitis are both bacterial skin infections, but they differ in how deep they go, how they look, and how they behave.

In summary, erysipelas is a more superficial skin infection with clearly defined, bright red edges, while cellulitis is a deeper infection that causes more diffuse redness and swelling. Both

need prompt antibiotic treatment, but erysipelas tends to look more dramatic and is slightly more superficial.

NICE (UK) treatment guidelines for cellulitis

NICE NG141 Guidance for Cellulitis and Erysipelas: Antimicrobial Prescribing covers the appropriate antimicrobial prescribing for people of all ages diagnosed with cellulitis or erysipelas. It excludes deeper infections (such as necrotising fasciitis), surgical cellulitis, bites, and complex hospital cases.

Key treatment and prescribing recommendations:

A. Exclude other plausible causes of redness, swelling, or skin changes before assuming cellulitis or erysipelas. Conditions such as insect bites, leg oedema, venous insufficiency, deep-vein thrombosis, or dermatitis may mimic presentation.

B. Choice of antibiotics (adults):

- First-choice: Oral flucloxacillin 500mg to 1g four times daily for five to seven days.

- If penicillin allergy or unsuitable: Clarithromycin, erythromycin (in pregnancy), or doxycycline (for five to seven days).

- If infection is near eyes or nose: Co-amoxiclav for seven days with specialist advice.

- For severe infections or MRSA risk: Intravenous options such as ceftriaxone or clindamycin may be used.

C. Route and duration:

Oral therapy is first line unless the patient is severely unwell or unable to take oral medication. Duration is typically five to seven days but may be extended if response is slow or complications arise.

D. Reassessment and review:

After starting treatment, reassess response to antibiotics and watch for signs of worsening such as systemic illness, lymphangitis, or involvement of deeper tissue. Review underlying factors such as diabetes, vascular disease, lymphoedema, or eczema. Once microbiology results are available, adjust antibiotic choice accordingly.

E. Referral or specialist advice:

Seek urgent referral if the patient is severely unwell, shows systemic signs (eg, sepsis), infection involves the face, spreads rapidly, or does not respond to oral therapy. Specialist input is also needed if unusual pathogens are suspected or the patient is immunocompromised.

Reference: Alexiou A, Scott J, and Narayanan

R. (2025) Cellulitis and erysipelas – symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment, BMJ Best Practice. Available at: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/ en-gb/63

F. Antimicrobial stewardship:

Use narrow- spectrum antibiotics whenever possible, for the shortest effective duration, and document the rationale for any deviation from guideline recommendations. Narrow-spectrum antibiotics include phenoxymethylpenicillin, flucloxacillin or ? for those allergic to penicillin ? options include clindamycin, erythromycin, or clarithromycin.

Practical implications for pharmacists and GPs Pharmacists and GPs should counsel patients on completing the full antibiotic course, monitoring for worsening symptoms, and seeking early review if infection spreads or systemic symptoms develop. Assess and manage pre- disposing factors such as broken skin, fungal infections, leg oedema, and poor hygiene. Liaise with prescribers to ensure appropriate antibiotic choice and monitor adverse effects or drug interactions.

3. Initial assessment and cleansing

Effective wound care begins with a careful initial assessment. For pharmacists, this involves observing the wound’s type, depth, location, cause, level of contamination, and risk of infection. This step determines whether the wound can be safely managed in the pharmacy or requires medical referral.

Pharmacists should start by asking a few simple but essential questions: When and how did the injury occur? Has the wound been cleaned? Are there any underlying conditions, such as diabetes or poor circulation, which may impair healing? A brief history helps to identify risk factors for delayed recovery or infection.

Cleansing is the cornerstone of wound management. The goal is to remove visible dirt, dried blood, and bacteria while avoiding trauma to new tissue. For most minor wounds, clean running tap water or sterile saline is adequate, both are effective, safe, and inexpensive. Antiseptic solutions such as povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine were once widely used, but evidence shows that these can delay healing and damage healthy tissue when used routinely. Their use should be limited to cases of gross contamination.

Where debris is embedded, gentle irrigation with saline and the use of sterile gauze can assist. If foreign material remains after cleansing (such as gravel or glass), referral for professional wound debridement is essential. Pharmacists should avoid using hydrogen peroxide, alcohol, or iodine tincture directly on wounds, as they can cause tissue irritation and unnecessary pain.

Minor bleeding usually stops after a few minutes of gentle pressure with clean dressing or sterile gauze. If bleeding persists beyond 10-15 minutes, or the wound is deep or pulsating, the patient should be referred for medical attention. Once bleeding is controlled, appropriate dressing can be applied to protect the area and maintain a moist healing environment. Pain management is an often-overlooked part of wound care. Over-the-counter (OTC) analgesics such as paracetamol or ibuprofen can provide relief and reduce inflammation. For superficial burns, a topical cooling hydrogel (eg, Burnshield, Intrasite gel, Nu-gel) or aloe vera preparation may help soothe discomfort when used appropriately. Pharmacists should remind patients to avoid applying greasy ointments, butter, or toothpaste to burns as these are old myths and, in fact, they can trap heat and increase infection risk.

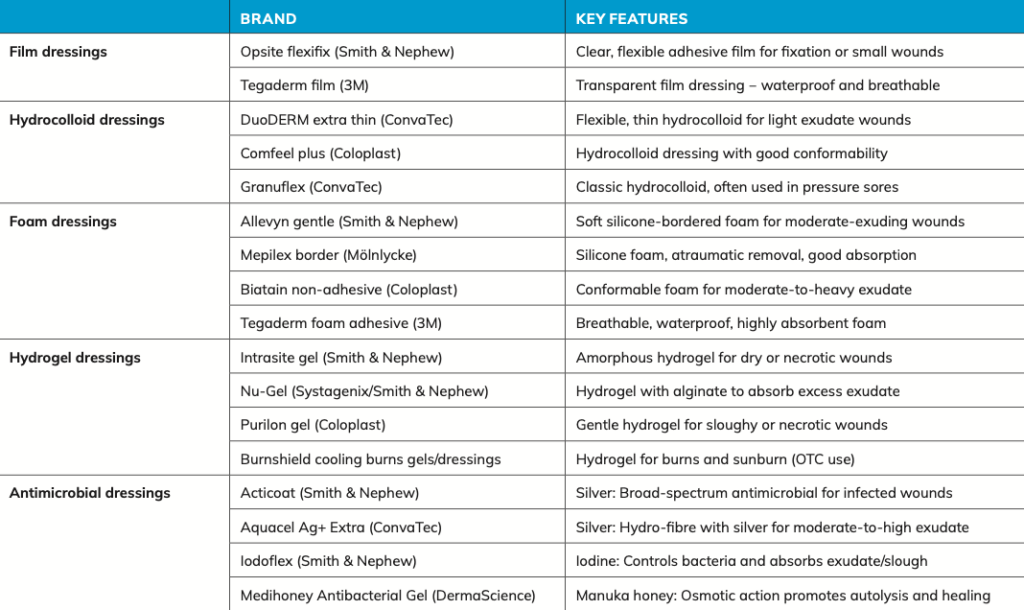

4. Dressing selection: Matching product to wound type

Selecting the right dressing is one of the most valuable contributions a pharmacist can make to wound care.

A well-chosen dressing protects the wound, maintains a moist but not wet environment, absorbs excess exudate, and minimises trauma when removed. The aim is to create the ideal conditions for epithelial regeneration while preventing infection and discomfort. The pharmacist’s decision should be guided by:

- Type of wound (acute, superficial, burn, blister, or post-surgical);

- Level of exudate (dry, low, moderate, or high);

- Presence of infection or necrosis;

- Patient factors, such as allergies, skin sensitivity, and ease of application.

Common dressing types in community pharmacy:

- Film dressings: Transparent and adhesive, ideal for superficial wounds, grazes, or blisters;

- Hydrocolloid dressings: Promote moist healing and autolytic debridement of dead tissue;

- Foam dressings: Highly absorbent and comfortable for moderate to heavily exuding wounds;

- Hydrogel dressings: Provide moisture to dry wounds and soothe burns;

- Antimicrobial dressings: Contain silver, iodine, or honey for infected or at-risk wounds.

Most modern dressings can remain in place for two to three days, depending on exudate. Over-frequent changes can disturb healing tissue, while leaving a saturated dressing too long can cause maceration. Advise to monitor leakage, odour, or pain which are signs that the dressing needs replacement.

Pharmacists involved in HSE dressing schemes must balance clinical need with approved formulary options on the likes of the PCRS Hardship Scheme or PCRS GP Stock Orders. Familiarity with the PCRS reimbursement list ensures both optimal patient care and cost-effective supply. By understanding dressing properties and aligning them with wound characteristics, pharmacists can significantly improve healing outcomes and patient satisfaction.

5. Managing minor burns

Burns are a common injury encountered in Irish pharmacies, particularly from household accidents such as scalds from hot liquids, contact with ovens, or steam. Pharmacists play a vital role in providing immediate advice, first aid, and appropriate aftercare, as well as identifying cases that require prompt referral. Understanding burn classification and early management principles is essential for preventing complications and promoting optimal healing.

The first priority in managing a burn is immediate cooling. Current guidance recommends cooling the affected area under cool running tap water for 20 minutes, ideally within three hours of injury. This helps reduce tissue damage, pain, and swelling. Ice, butter, toothpaste, or oil-based products should never be applied, as these can worsen tissue injury and increase infection risk.

Once cooled, gently remove any jewellery or tight clothing before swelling develops, but avoid peeling away fabric stuck to the wound. For burns caused by chemicals, prolonged irrigation is vital, followed by medical referral.

Pharmacists should be familiar with the three main classifications of burn depth:

- Superficial (first-degree) ? red, dry, and painful without blistering;

- Superficial partial thickness (second- degree) ? red, moist, blistered, and painful;

- Deep partial-thickness or full-thickness (third-degree) ? pale or charred, often painless, requires urgent referral.

Burns greater than 3cm in diameter, or those involving the face, hands, feet, genitals, or major joints, should always be referred, as should burns in children, older adults, or people with diabetes or poor circulation.

After cooling, superficial burns may be covered with a sterile, non-adherent, or hydrogel dressing to protect the area and maintain moisture. Analgesia with paracetamol or ibuprofen is usually sufficient. The area should be kept clean and protected from friction or sunlight while healing. Pharmacists should advise review if blisters enlarge, pain worsens, discharge develops, or healing does not occur within two weeks.

6. Infection prevention and red flags

Preventing infection is one of the most important aspects of wound management. Even minor wounds or superficial burns can become infected if they are not properly cleaned, covered, or monitored. Pharmacists are ideally positioned to identify early signs of infection, provide antimicrobial guidance, and refer patients when appropriate.

Infection typically presents with increased pain, swelling, redness, warmth, and exudate around the wound. A wound that appears healthy should gradually improve ? if it becomes more inflamed or starts to discharge pus, infection should be suspected. Systemic symptoms such as fever or swollen lymph nodes indicate more serious infection and warrant immediate referral.

Most clean wounds do not require routine antiseptics or antibiotics. However, in wounds with high bacterial load or early infection signs, short-term topical antimicrobial therapy may be appropriate, such as fusidic acid cream, iodine or silver dressings, or honey-based preparations. These should be reviewed after a few days and stopped if no improvement is seen. Systemic antibiotics should only be considered when infection spreads or are accompanied by systemic signs. Flucloxacillin is the typical first-line choice for patients’ not allergic to pencillin. Erythromycin or clarithromycin are options for those who are allergic. See Cellulitis: Section 2F above for more details on antibiotic choices.

Any wound contaminated with soil, manure, or rust should trigger a tetanus immunisation check. Patients unsure of their vaccination status should be referred to their GP. Pharmacists should also advise proper hand hygiene, regular dressing changes, and prompt medical review if infection signs worsen. Through clean technique and prudent antimicrobial use, pharmacists help prevent complications and support safe wound healing.

7. Pressure sores

Pressure sores are not considered minor wounds. However, it is important for pharmacists to be able to distinguish a pressure sore or a wound that has the possibility of developing into a pressure sore hence their inclusion here. Moe detail on pressure sores is available via Pharmacist online.

Pressure ulcers (bedsores) are localised injuries to the skin and underlying tissue, usually caused by prolonged pressure over a bony prominence. They develop when blood flow is reduced due to compression between bone and an external surface, leading to tissue ischemia and necrosis.

Clinical features and diagnosis

Pressure ulcers are recognised by their typical location and appearance. They must be differentiated from other ulcers:

- Diabetic neuropathic ulcers occur on the foot (especially under the big toe or on the tops of toes) due to neuropathy.

- Venous ulcers (about 70 per cent of leg ulcers) appear on the inner lower leg above the ankle, often in swollen, discoloured areas with flaky or itchy skin. These benefit from elevation and compression.

- Arterial ulcers (10 per cent of leg ulcers) result from poor circulation, presenting as painful, cold, pale, or bluish wounds on the feet or lower legs. Pain increases on elevation.

- Superficial moisture-related skin breakdown (maceration) should not be mistaken for pressure ulcers.

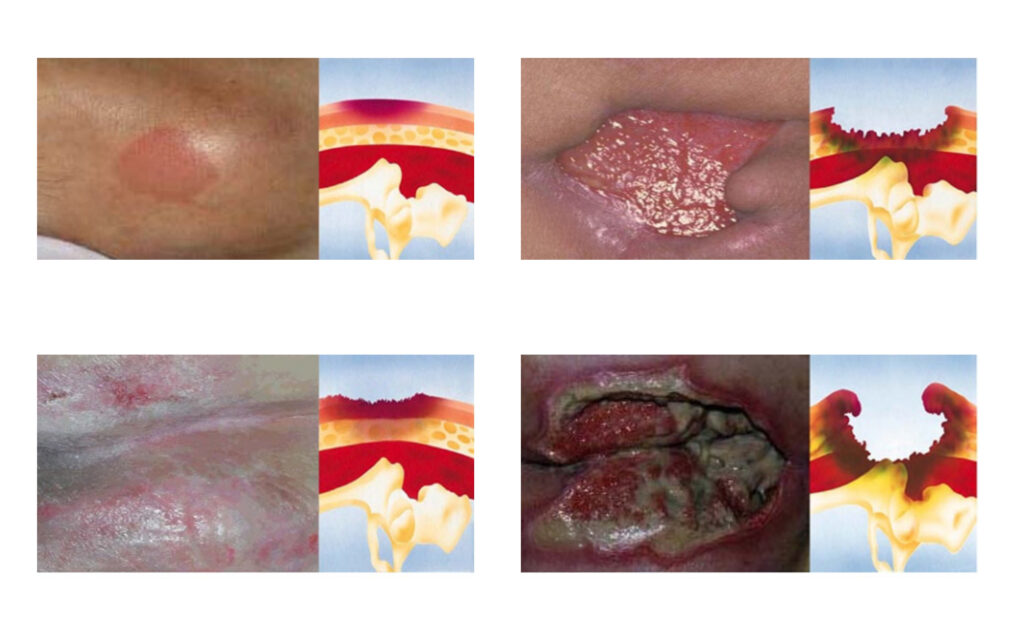

Classification (EPUAP grading system)

Grade 1: Persistent redness (non- blanching), sometimes with warmth or hardness ? may appear blue/purple in dark skin.

Grade 2: Partial skin loss (epidermis/ dermis), seen as an abrasion or blister ? bruising suggests deeper injury.

Grade 3: Full skin loss with damage to subcutaneous tissue, but no exposure of muscle or bone ? may contain slough. Grade 4: Deep destruction involving muscle, bone, or supporting structures, often leading to serious infection. Unstageable: Full-thickness loss where the base is obscured by slough or eschar ? true depth can’t be determined until cleaned.

Prevention and management

Preventative strategies are crucial:

- Repositioning ? regular turning or movement to relieve pressure.

- Pressure-relieving equipment ? special beds, cushions, and mattresses.

- Managing comorbidities ? conditions like poor circulation or diabetes must be optimised.

- Local wound care ? use of modern dressings and wound technologies.

Patients with Grade 1 ulcers are at high risk and require proactive management to prevent progression.

Pain management

Pain from pressure ulcers can be severe and disabling:

- Paracetamol may suffice for mild pain;

- Opioids may be needed for moderate to severe cases;

- NSAIDs (eg, ibuprofen, diclofenac) are generally avoided due to risk of oedema;

- Topical anaesthetics like lidocaine can offer short-term relief during procedures.

If pain is poorly controlled, referral to a pain clinic may be appropriate. Dressing and debridement techniques should be adjusted to minimise discomfort.

Nutrition

Adequate nutrition is vital for healing.

- Aim for 1.5g protein/kg/day ? supplement if intake is poor;

- Oral Nutritional Supplements (ONS) such as Cubitan (high protein, with arginine, zinc, vitamins C and E) may support healing in malnourished patients.

However, these should only be used after dietitian assessment, reviewed regularly, and discontinued once wounds heal, given cost and limited evidence on optimal use.

Dressings

Evidence on the most effective dressing is inconclusive, but modern options are preferred:

- Transparent films (eg, Tegaderm, Opsite) for Grade 1;

- Occlusive or semi-permeable dressings (eg, Comfeel Plus, Granuflex) for Grade 2;

- Absorptive dressings (Kaltostat, Allevyn, Biatain) for wounds with heavy exudate;

- Hydrogels (Granugel, Intrasite Gel) for dry wounds to maintain moisture balance.

Debridement

Removing necrotic tissue promotes healing and prevents infection. Methods include:

- Sharp debridement (surgical);

- Mechanical (wet-to-dry dressings);

- Enzymatic;

- Autolytic (using hydrocolloids/hydrogels);

- Biosurgery (sterile maggots).

Infection control

Meticulous hygiene is essential:

- Hand washing, cleansing, and protecting wounds from contamination;

- Increased cleansing/debridement for infected or odorous wounds;

- X-rays may be needed to rule out osteomyelitis if infection persists.

Systemic antibiotics are indicated for sepsis, cellulitis, bacteraemia, or bone infection.

8. Patient counselling and aftercare

Effective wound management does not end once the dressing is applied. The pharmacist’s role continues through patient education, follow-up advice, and reassurance, ensuring that the wound heals safely and that the patient knows when to seek further care.

Patients should be advised to keep the wound clean and protected. Dressings should remain in place until the next scheduled change or sooner if they become loose, wet, or heavily soiled.

A slightly moist environment supports healing ? wounds should not be left uncovered to ‘dry out’.

Encourage handwashing before and after dressing changes and discourage unnecessary touching or checking under the dressing. Smoking cessation and good nutrition (adequate protein, zinc, and vitamin C) are key to healing. Diabetic patients should maintain good blood glucose control. Mild pain can be managed with paracetamol or ibuprofen. Avoid unproven home remedies or topical anaesthetics on open wounds.

Patients should be advised to monitor for changes such as worsening pain, redness, odour, or delayed healing beyond 10-14 days and seek medical advice if these occur. Check tetanus vaccination status where relevant. By providing practical aftercare guidance, pharmacists empower patients and reinforce their role as trusted healthcare professionals in the community.

Disclaimer: Brands mentioned in this article are meant as examples only and not meant as preference to other brands.

References

1. NICE (2019) Cellulitis and erysipelas: Antimicrobial prescribing (NG141). London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Available at: https://www. nice.org.uk/guidance/ng141 (Accessed: 25 October 2025).

2. NICE (2016) Burns and scalds: Recognition and management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

3. Health Service Executive (HSE) (2023) Aseptic technique and wound management. Dublin: HSE Clinical Guidance and Standards.

4. HSE (2024) Primary Care Reimbursement Service (PCRS): Wound dressing formulary 2024. Dublin: HSE. 5. Public Health England (2020) Managing common infections: Guidance for primary care. London: PHE Publications.

6. World Health Organisation (WHO) (2018) Antimicrobial stewardship: Practical guide for health care professionals. Geneva: WHO.

7. British National Formulary (BNF) (2025) Wound management, infections, and burns. London: BMJ Group and RPS Publishing.

8. Harding KG and Queen D. (2019) Wound management in primary care. Pharmaceutical Journal, 303(7925), p 245-252.

9. Barrett S. 2020 Minor wound care in community pharmacy: An evidence-based approach. Clinical Pharmacist, 12(2), p 45-50.

10. Ousey K and Atkin L. (2021) Moist wound healing: Revisiting the evidence. Journal of Wound Care, 30(6), p 422-430.

11. Thomas S. (2017) A structured approach to wound management. Cardiff: Welsh Wound Innovation Centre.

12. Cutting KF and Harding KG. (2015) Criteria for dentifying wound infection. Journal of Wound Care, 24(5), p 233-240.

13. Irish Health Protection Surveillance Centre (HPSC) (2023) Guidelines for the prevention and management of cellulitis and skin infections. Dublin: HPSC.

14. NICE (2019) Antimicrobial stewardship: Systems and processes for effective antimicrobial medicine use (NG15). London: NICE.

15. NHS (2024) How to treat burns and scalds. London: National Health Service.

16. Moore Z and Cowman S. (2019) Best practice in wound assessment and management. Nursing Standard, 34(8), p 61-68.

17. Cooper R and Jenkins L. (2018) Honey in wound care: Antimicrobial and healing properties. Wounds UK, 14(3), p 20-28.

18. Jones V, Grey JE, and Harding KG. (2006) ABC of wound healing: Wound dressings. BMJ, 332(7544), p 777-780.

19. Gupta S and Andersen C. (2019) Silver dressings in wound management. Advances in Wound Care, 8(4), p 169-176.

20. NICE (2023) Chronic wounds: Assessment and management. London: NICE Evidence Services.

21. Health Products Regulatory Authority (HPRA) (2024) Topical antiseptics and antimicrobial dressings: Guidance for pharmacists. Dublin: HPRA.

22. World Health Organisation (WHO). Burns: Key Facts. Geneva: WHO; updated 2023. https://www. who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/burns.

23. British National Formulary (BNF). Management of burns. London: NICE and BMJ Publishing Group; 2023. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/.

24. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Burns and scalds – clinical knowledge summary (CKS). Updated 2023. https://cks.nice.org.uk/ topics/burns-scalds/.

25. Mayo Clinic. Burns – symptoms and causes. Rochester, MN: Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research; 2023. https://www. mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/burns/.

26. American Burn Association (ABA). Burn injury model systems and classification. 2022. https:// ameriburn.org/.

27. Health Service Executive (HSE) Ireland. Burns – first aid and treatment guidance. Dublin: HSE; 2022. https://www.hse.ie/eng/.

28. European Burn Association (EBA). Classification of burn depth and severity. Brussels: EBA; 2021. https:// www.euroburn.org/.

29. European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP). Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: Quick Reference Guide. 2019.

30. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Pressure ulcers: Prevention and management (CG179). 2014.

31. Health Service Executive (HSE). Guidelines for the prevention and management of pressure ulcers. Dublin, 2022.

32. National Medicines Information Centre (NMIC), St James’s Hospital. Oral nutritional supplements and wound healing. Bulletin, 2021.

33. Huntleigh Healthcare Ltd. EPUAP Grading System Reference Table. 2020.

34. European Wound Management Association (EWMA). Debridement: An updated overview and clarification of the principal role of debridement. J Wound Care, 2020.

35. World Health Organisation (WHO). Pressure ulcer prevention: Technical report. Geneva, 2019.