Eamonn Brady MPSI provides a clinical overview of psoriasis and how pharmacists can help to influence outcomes

Contents

- What is psoriasis?

- Psoriasis as a systemic disease

- Types of psoriasis

- Diagnosis

- Pharmacists at the frontline of prevention

- Lifestyle modification and preventive counselling

- Screening and comorbidity prevention

- Psoriasis pharmacological treatment

- Medication optimisation and preventing flare-ups

- Looking ahead: The future of psoriasis prevention in pharmacy

- Communication and patient engagement in psoriasis care

- Evolving pharmacy practice in Ireland

- References

What is psoriasis

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated, inflammatory condition that affects approximately 2 per cent

in Ireland and 2-3 per cent in the UK and wider Europe. While it is most often recognised by its visible skin plaques, psoriasis is increasingly understood as a systemic disease with wide-ranging implications for health and wellbeing. Beyond physical discomfort, psoriasis is associated with stigma, reduced quality of life, and an elevated risk of comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), type 2 diabetes, and depression.

Against this backdrop, pharmacists are ideally placed to contribute to prevention and management. As the most accessible healthcare professionals, they can provide practical advice, early recognition, medication optimisation, and ongoing support. This article explores the evolving role of pharmacists in preventative psoriasis care, highlighting how everyday practice can make a significant difference for patients and the wider health system.

Psoriasis as a systemic disease

Historically regarded as a dermatological problem, psoriasis is now firmly established as a systemic inflammatory condition. The ‘psoriatic march’ describes the pathway from chronic skin inflammation to insulin resistance, dyslipidaemia, hypertension, and ultimately CVD. Around one-third of patients will develop psoriatic arthritis, and many also experience psychological distress or depression linked to the visible nature of the condition.

Recognising psoriasis in this broader context underscores the importance of holistic care. Preventive interventions that address both skin symptoms and associated comorbidities can reduce the long-term health burden. Pharmacists, with their expertise in medicines and frequent patient contact, are central to delivering this integrated approach.

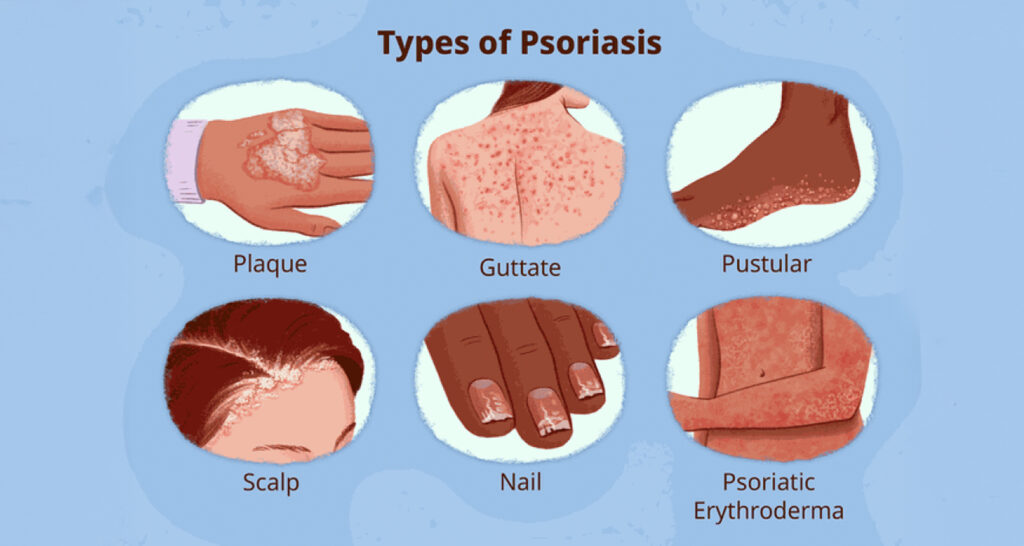

Types of psoriasis

Psoriasis manifests in multiple clinical forms such as plaque, guttate, inverse, pustular, erythrodermic as well as common nail and scalp involvement. Each type has distinct epidemiology, presentations, prognosis, and management considerations.

1. Plaque psoriasis (Psoriasis vulgaris)

Epidemiology: Most common (80-90 per cent of cases) with equal male and female prevalence; typically begins between the age of 15 and 35.

Clinical features: Well-demarcated red plaques with silvery-white scale, often on extensor surfaces, scalp, and trunk. Course: Chronic, relapsing, lifelong management. Flare triggers include infections, stress, certain medications, and trauma.

2. Guttate psoriasis

Epidemiology: Common among children and young adults, often after a streptococcal throat infection.

Clinical features: Multiple small, drop-like lesions scattered across trunk and limbs. Course: Often acute with spontaneous resolution within weeks to months – up to 40 per cent may progress to chronic plaque psoriasis.

3. Inverse (flexural) psoriasis

Epidemiology: Occurs in skin folds, common in obese or diabetic patients but can affect any age.

Clinical features: Shiny, smooth red patches without scale in groin, axillae, or infra-mammary regions.

Course: Chronic and recurrent – aggravated by friction, moisture, and heat.

4. Pustular psoriasis

Epidemiology: Rare and more severe form, seen mostly in adults.

Clinical features: Sterile pustules on red skin. Can be localised (palms/soles) or generalised.

Course: Localised forms are chronic ? generalised form is acute, potentially life-threatening.

5. Erythrodermic psoriasis

Epidemiology: Very rare ? usually occurs in unstable or poorly treated psoriasis.

Clinical features: Widespread redness, scaling, and skin shedding over >90 per cent of body surface. Often with fever, malaise.

Course: Acute, life-threatening ? requires immediate specialist referral.

6. Nail psoriasis

Epidemiology: Affects up to 50 per cent of psoriasis patients, particularly those with psoriatic arthritis.

Clinical features: Pitting, onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, oil-drop discolouration.

Course: Chronic nail involvement often precedes arthritis.

7. Scalp psoriasis

Epidemiology: Affects up to 80 per cent of psoriasis patients during their disease course.

Clinical features: Thick, adherent scales on scalp, sometimes extending to forehead or hairline.

Course:Chronic and recurrent; may overlap with seborrhoeic dermatitis.

Psoriasis diagnosis in Ireland

Diagnosis in Ireland, as elsewhere, relies on a combination of clinical assessment, patient history, and standardised severity scoring tools such as the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI).

Diagnosis

In Ireland, psoriasis is usually diagnosed in primary care or by dermatologists based on clinical appearance. Laboratory or histological tests are rarely required unless the diagnosis is uncertain. Severity is assessed not only by the extent of skin involvement but also by its effect on daily life. Dermatology services within the HSE may use internationally recognised scoring systems, with PASI being the most common, particularly in specialist settings or clinical trials.

PASI

PASI is a clinical tool designed to quantify disease severity. It measures the extent

of psoriasis and the degree of redness, thickness, and scaling across four regions of the body (head, upper limbs, trunk, and lower limbs). Each region is scored separately and then combined into an overall PASI score, which can range from 0 (no psoriasis) to 72 (maximal disease severity).

How PASI scoring is also used to determine treatment improvement PASI 75 and higher PASI 75 refers to a 75 per cent or greater improvement in the PASI score from baseline. It has historically been the benchmark used in clinical trials to define significant improvement. Patients achieving PASI 75 generally experience a substantial reduction in symptoms and visible plaques. Although not always synonymous with complete clearance, PASI 75 is considered a clinically meaningful response.

Other PASI benchmarks

- PASI 50: 50 per cent improvement – minimal but noticeable clinical response.

- PASI 75: 75 per cent improvement – significant improvement; traditional trial standard.

- PASI 90: 90 per cent improvement – near-clearance, often reached with modern biologic therapies.

- PASI 100: 100 per cent improvement – complete clearance of psoriatic lesions.

Clinical relevance in the Irish context Historically, conventional systemic therapies

| TYPE | AFFECTED POPULATION | DURATION / PROGNOSIS |

| Plaque | Adults, both sexes | Lifelong, chronic relapsing |

| Guttate | Children/young adults post-strep | Often acute ? may remit or become chronic |

| Inverse | Any age: Obese/diabetics predisposed | Chronic, fluctuating |

| Pustular | Rare, mostly adults | Localised: Chronic Generalised: Acute emergency |

| Erythrodermic | Unstable/severe psoriasis cases | Acute, life-threatening |

| Nail | Psoriasis ± psoriatic arthritis | Chronic, slow improvement |

| Scalp | Most psoriasis patients | Chronic, recurrent |

Table 1: Type of psoriasis: Summary

such as methotrexate, ciclosporin, and phototherapy could deliver PASI 50 or PASI 75 responses in many patients, but relapse was common. With the availability of modern biologic therapies through HSE’s High-Tech Drug Scheme, more patients are now achieving PASI 90 or even PASI 100 responses, representing near or complete clearance of lesions. Dermatologists in Ireland often use PASI scores to determine eligibility for advanced therapies, with PASI 75 serving as an important treatment milestone.

Pharmacists at the frontline of prevention

Community pharmacies are often the first port of call for individuals seeking help with skin concerns. For patients with psoriasis, pharmacists can play a role in:

- Recognition and education: Helping patients differentiate psoriasis subtypes and dispel myths (not contagious).

- Provide early recognition and referral: Identifying plaques on the scalp, elbows, knees, or other typical sites, and advising when GP or dermatology referral is needed.

- Identifying red flags: Rapid worsening, systemic symptoms, pustular/erythrodermic signs. Asking simple screening questions about joint stiffness or swelling can highlight psoriatic arthritis at an early stage, thus identifying urgent referral.

- Comorbidity awareness: Psoriatic arthritis, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular risks, and mental health impacts.

- Supporting treatment adherence: Many patients struggle with the complexity of topical regimens. Pharmacist counselling on correct application, dosing intervals, and duration can greatly improve outcomes.

Lifestyle modification and preventive counselling

Lifestyle factors are well-recognised in psoriasis onset and exacerbation. Pharmacists can play a leading role in supporting patients to adopt healthier behaviours:

- Smoking cessation: Smoking is strongly linked to both the incidence and severity of psoriasis. Pharmacist-led quitting services, including nicotine replacement therapy, are proven to improve quitting rates.

- Weight management: Obesity is associated with worse disease control and reduced response to biologics. Pharmacists can provide structured weight management support and reinforce the benefits of even modest weight loss.

- Alcohol moderation: High alcohol intake is a trigger for flare-ups and poor adherence. Pharmacists can provide screening, brief interventions, and referral to support services.

- Stress management: Stress is a well- known trigger for psoriasis exacerbations. Pharmacists can signpost patients to counselling, mindfulness resources, or GP mental health services.

Screening and comorbidity prevention

Psoriasis is not just a skin disease and it carries significant systemic risks. Pharmacists can use their existing service frameworks to screen for and address comorbidities:

- Cardiovascular risk checks: Blood pressure monitoring, cholesterol testing, and diabetes screening can be offered in community pharmacies. Patients with psoriasis are at higher risk of CVD, so early detection and referral are essential.

- Mental health support: Depression and anxiety are common but often under-recognised in psoriasis patients. Pharmacists can start sensitive conversations, normalise help-seeking, and signpost support services.

- Psoriatic arthritis awareness: Pharmacists can routinely ask about joint stiffness, morning pain, or swelling, and recommend GP referral when appropriate.

Psoriasis treatment: Pharmacological options

The therapies used for psoriasis can be split into four sections. They are:

1. Topical therapies;

2. Phototherapy and transition to systemics;

3. Conventional systemic therapies;

4. Biologic therapies.

1. Topical therapies – First-line management

For most patients with mild to moderate psoriasis, topical therapy is the first-line treatment. Pharmacists play a crucial role in counselling on correct use, which is essential to prevent treatment failure.

Emollients: Used as baseline therapy, emollients reduce scaling, hydrate skin, and improve comfort. Different formulations exist (ointments, creams, gels), each with unique benefits. Ointments are highly occlusive and best for dry plaques, while creams may be preferred for daytime use due to lighter texture. Gels and lotions can be particularly helpful for scalp psoriasis. Pharmacists should advise patients to apply emollients liberally, ideally within minutes of bathing, and use them in conjunction with active therapies.

Corticosteroids: Corticosteroids are categorised by potency ? mild (hydrocortisone), moderate (clobetasone butyrate), potent (betamethasone valerate, mometasone), and very potent (clobetasol propionate).

Potency selection depends on site and severity ? mild agents for the face/ flexures, potent or very potent agents for thick plaques on elbows, knees, and scalp. Risks include skin atrophy, striae, telangiectasia, tachyphylaxis, and rebound flares. Safe use strategies include fingertip unit guidance, step-down therapy, and short bursts of potent steroids followed by emollients or weaker steroids.

Vitamin D analogues: Topical drugs such as calcipotriol, calcitriol, and tacalcitol inhibit keratinocyte proliferation and are effective for plaque psoriasis.

They are often used in combination with corticosteroids to enhance efficacy and reduce steroid exposure. Combination formulations (calcipotriol + betamethasone dipropionate) improve adherence. Weekly dosing should not exceed 100g calcipotriol equivalent due to risk of hypercalcaemia. Pharmacists should advise patients about potential skin irritation and the importance of applying vitamin D analogues separately from salicylic acid products.

Coal tar and dithranol: Historically important, these remain relevant in refractory psoriasis. Coal tar has anti- inflammatory and antiproliferative effects but is less commonly used due to odour, staining, and messiness.

Dithranol is effective but irritant and typically used in hospital-supervised short- contact regimens. Both can still play a role in specialised cases.

Other topical therapies: Calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus, pimecrolimus) are sometimes used off-label for sensitive sites (face, flexures). Salicylic acid and other keratolytics may be added to remove scale and improve penetration of active therapies.

2. Phototherapy and transition to systemics

When topicals prove insufficient, phototherapy is a key next step. Narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) is the standard option, usually given two to three times weekly for up to 12 weeks. It induces remission in many patients and is relatively safe with limited cumulative risk. Relapse is common within six to 12 months, so it is often repeated. PUVA (psoralen + UVA) is now less common due to skin cancer risk but remains useful in severe, refractory cases. Pharmacists can advise on emollient use, sun protection, and realistic expectations.

3. Conventional systemic therapies

Methotrexate Mechanism: Methotrexate is a folate antagonist that inhibits DNA synthesis and has anti-inflammatory properties. It is considered the gold standard systemic therapy for psoriasis.

Dosing: Administered once weekly (oral, subcutaneous, or intramuscular). Doses typically start at 7.5-15mg weekly, increasing to 25mg as tolerated. Monitoring: Requires baseline FBC, LFT, U&E, hepatitis, and TB screening, and pulmonary assessment (CXR or history). Regular blood tests every one to two weeks initially, then every two to three months. Monitor for hepatotoxicity, bone marrow suppression, and pulmonary fibrosis. Counselling: Folic acid supplementation (on non-methotrexate days), avoidance of alcohol, contraception advice, infection risks, and early recognition of side effects (mouth ulcers, cough, breathlessness). Avoid methotrexate with alcohol (hepatotoxicity).

Ciclosporin

Mechanism: A calcineurin inhibitor that suppresses T-cell activation. Very effective but limited by nephrotoxicity and hypertension.

Use: Reserved for severe, refractory psoriasis, especially where rapid control is needed. Usually limited to ?12 months use. Monitoring: Blood pressure and renal function every two to four weeks initially, then every one to three months. Drug interactions are common (CYP3A4). Grapefruit juice, macrolides, and azoles should be avoided. Avoid ciclosporin with nephrotoxic drugs (NSAIDs, aminoglycosides antibiotics like neomycin).

Acitretin (Neotigason oral capsules)

It’s not a hi-tech medicine.

Mechanism: Oral retinoid that normalises keratinocyte differentiation.

Use: Best for severe, resistant psoriasis. Limited by teratogenicity and women must avoid pregnancy for three years post-treatment. Mostly used in men and post-menopausal women. Side-effects include dry skin, cheilitis, hair thinning, photosensitivity, and hyperlipidaemia. Monitoring: Baseline and regular LFTs and lipids are required.

Apremilast (Otezla 10, 20, or 20mg tablets)

A hi-tech medicine so can only be initiated by a consultant.

Mechanism: A phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) inhibitor that reduces pro- inflammatory cytokine activity.

Counselling: Side effects include diarrhoea, nausea, headache, weight loss, and depression. Requires renal dose adjustment in impairment. Has the advantage of being oral administration with less intensive monitoring.

4. Biologic therapies for psoriasis Biologic therapies have revolutionised

the management of moderate-to-

severe psoriasis, particularly for patients who have not responded to topical, phototherapy, or conventional systemic treatments. They are targeted protein- based therapies designed to interfere with specific immune pathways involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Pharmacists play a key role in supporting patients who are prescribed biologics, from counselling and adherence to safety monitoring. All biologics are hi-tech medicine so can only be initiated by a consultant.

Key points for Ireland:

- Psoriasis go-to biologics now: IL-17s (secukinumab, ixekizumab) and IL-23s (guselkumab, risankizumab).

- Older biologics (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab) are mainly used in arthritis/IBD, not psoriasis.

- Ustekinumab (Stelara) remains relevant in psoriasis, though newer IL-23s are overtaking it.

- Ustekinumab (Uzpruvo) is a new ustekinumab biosimilar and is the first approved ustekinumab biosimilar in Ireland.

Mechanism of action by class

Biologics used in psoriasis primarily target cytokines that drive inflammation and keratinocyte proliferation:

- TNF-? inhibitors: Adalimumab (Humira, Amgevita), etanercept (Enbrel, Benepali), infliximab (Remicade Remicade) ? block tumour necrosis factor-alpha, reducing systemic inflammation.

- IL-12/23 inhibitor: Ustekinumab (Stelara) and ustekinumab (Uzpruvo): Targets the shared p40 subunit of interleukin-12 and interleukin-23, modulating Th1/Th17 pathways.

- IL-17 inhibitors: Secukinumab (Cosentyx), ixekizumab (Taltz), brodalumab (Kyntheum): Directly block IL-17A or its receptor, suppressing keratinocyte activation and plaque formation.

- IL-23 inhibitors: Guselkumab, Risankizumab (Skyrizi), tildrakizumab (Ilumetri): Selectively block the p19 subunit of IL-23, disrupting the IL-23/IL-17 axis and reducing chronic inflammation.

Efficacy and time to response

Biologics are highly effective, with many achieving Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 75 or higher in the majority of patients:

- TNF-? inhibitors: PASI75 in approximately 60 to 70 per cent of patients at 12 to 16 weeks; slower onset than IL-17/23 inhibitors.

- IL-12/23 inhibitors: Ustekinumab achieves PASI75 in approximately 70 per cent of patients by 12 weeks ? long dosing interval improves adherence.

- IL-17 inhibitors: Rapid onset, often achieving visible clearance within two to four weeks; PASI 90 in 70-80 per cent by 12 weeks.

- IL-23 inhibitors: Among the most effective, achieving PASI 90 in 70 to 90

per cent of patients ? durable remission lasting months with maintenance dosing every eight to 12 weeks.

Indications and prescribing criteria Biologics are generally reserved for adults with severe plaque psoriasis (PASI ?10, DLQI ?10) where conventional systemics (methotrexate, ciclosporin, acitretin) are ineffective, contraindicated,

| CLASS | DRUG | BRAND NAME(S) IN IRELAND | MAIN IRISH USE |

| Anti-TNF | Adalimumab | Humira, Amgevita | Mostly arthritis and Crohn’s disease; psoriasis use is declining |

| Anti-TNF | Etanercept | Enbrel, Benepali | Historically psoriasis, but now rarely used; still used in arthritis |

| Anti-TNF | Infliximab | Remicade | Mainly IBD and arthritis; psoriasis only in severe cases |

| IL-12/23 inhibitor | Ustekinumab | Stelara | Psoriasis (still widely used); also Crohn’s disease |

| IL-12/23 inhibitor | Ustekinumab | Uzpruvo | Indicated for plaque psoriasis, paediatric plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, Crohn’s disease |

| IL-17 inhibitor | Secukinumab | Cosentyx Taltz | First-line psoriasis; also arthritis |

| IL-17 inhibitor | Ixekizumab | Taltz | Very common psoriasis option |

| IL-17 inhibitor | Brodalumab | Kyntheum | Psoriasis only, less frequently chosen |

| IL-23 inhibitor | Guselkumab | Tremfya | Widely used psoriasis biologic |

| IL-23 inhibitor | Risankizumab | Skyrizi | Common psoriasis treatment |

| IL-23 inhibitor | Tildrakizumab | Ilumetri | Psoriasis only, less common than guselkumab/Risankizumab |

| IL-12/23 inhibitor | Ustekinumab | Wezlana | Adults and pediatric patients 6 years of age and older with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who are candidates for phototherapy or systemic therapy |

| IL-12/23 inhibitor | Ustekinumab | Imuldosa | Used for the treatment of plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis |

Table 2: Summary of biologics in psoriasis (Ireland)

or not tolerated. They are also used in patients with psoriatic arthritis. In Ireland and the UK, prescribing

is restricted to dermatologists or rheumatologists, with initiation often guided by NICE or HSE criteria.

Administration and practicalities

Most biologics for psoriasis are given by subcutaneous self-injection, with training provided by specialist nurses or pharmacists. Some, such as infliximab, require hospital-based intravenous infusion. Examples:

- Adalimumab: Subcutaneous injection every two weeks ? patients usually self- administer after training.

- Etanercept: Subcutaneous once or twice weekly.

- Infliximab: Intravenous infusion at 0, two, six weeks, then every eight weeks in hospital.

- Ustekinumab: Subcutaneous injection at weeks 0, four, then every 12 weeks. Uzpruvo is a cost-effective option enabling improved access to ustekinumab treatment and has equivalent efficacy, safety and immunogenicity to the reference product.

- IL-17 inhibitors: Subcutaneous, typically every two-to-four weeks.

- IL-23 inhibitors: Subcutaneous every eight to 12 weeks after loading.

Best suited psoriasis types

Biologics are most effective for chronic plaque psoriasis but are also useful for difficult-to-treat forms:

- Scalp and nail psoriasis: IL-17 and IL-23 inhibitors show strong evidence of efficacy.

- Erythrodermic and pustular psoriasis: Infliximab and IL-17 inhibitors can be life-saving.

- Psoriatic arthritis: TNF-?, IL-17, and IL-23 inhibitors improve both skin and joint symptoms.

Safety, monitoring, and contraindications Before initiating biologics, patients must

be screened for tuberculosis, hepatitis B and C, and HIV. Vaccinations should be updated, with live vaccines contraindicated during therapy. Ongoing monitoring includes infection surveillance, malignancy risk assessment, and periodic laboratory checks. Specific cautions:

- TNF-? inhibitors: Contraindicated in demyelinating disease and severe heart failure.

- IL-17 inhibitors: Can exacerbate inflammatory bowel disease.

- IL-23 inhibitors: Generally well tolerated ? long-term safety data are still being collected.

Pharmacist role

Pharmacists support biologic therapy by:

- Providing injection training and ensuring correct technique.

- Maintaining cold-chain storage and advising on travel/stability.

- Screening for contraindications (ie, live vaccines, active infections).

- Counselling on expected time to response and adherence.

- Monitoring side effects and reporting adverse events to HPRA/Yellow Card Scheme.

- Supporting patients with comorbidities and liaising with dermatology/ rheumatology teams.

Biosimilars and cost considerations Biosimilars of adalimumab, etanercept,

and infliximab are now widely available, offering significant cost savings. Switching patients from originators to biosimilars is increasingly common in Ireland and the UK, with careful counselling to maintain patient confidence and adherence. Pharmacists are crucial in explaining biosimilars’ equivalence and ensuring smooth transitions.

Future directions for biologics

Emerging biologics continue to refine psoriasis treatment, with newer IL-23 inhibitors showing even greater efficacy and durability. Research into oral biologic- like agents, personalised medicine using biomarkers, and integration with digital health monitoring is ongoing.

Medication optimisation and preventing flare-ups

Correct use of medicines is vital in preventing flare-ups and improving control.

Ongoing monitoring includes infection surveillance, malignancy risk assessment, and periodic laboratory checks

Pharmacists can support patients in several ways:

- Topical therapy guidance: Emollients, vitamin D analogues, and corticosteroids remain the cornerstone of first-line management. Counselling on fingertip unit application, frequency, and safe use of potent steroids prevents both under- treatment and side effects.

- Combination therapies: Many patients receive stepwise regimens. Pharmacists can explain sequencing and reinforce step- down strategies to avoid rebound flares.

- Systemic and biologic therapy support: Patients prescribed methotrexate, ciclosporin, or biologics require monitoring, infection prevention, and adherence support. Pharmacists can check for drug interactions, emphasise the importance of vaccinations, and encourage adherence to monitoring schedules.

- Drug interaction awareness: Drugs such as beta-blockers, lithium, antimalarials, ACE inhibitors, interferons, and NSAIDs can exacerbate psoriasis. Pharmacists are ideally placed to identify potential triggers and liaise with prescribers.

Looking ahead: Future medicines and Pharmacy’s role The therapeutic pipeline for psoriasis is expanding. Oral JAK inhibitors and novel IL- 23 blockers are in development, promising more convenient and effective treatment options. As the range of therapies grows, pharmacists will be essential in guiding patients through increasingly complex treatment pathways.

Future practice will likely involve:

- Shared care protocols with dermatology, especially for monitoring biologics.

- Vaccination services integrated with biologic therapy counselling.

- Digital health tools supported by pharmacists to improve adherence and self-monitoring.

Pharmacists at the forefront of psoriasis care

Psoriasis is characterised by erythematous, scaly plaques that often flare and remit, with significant implications for physical comfort, mental health, and long-term comorbidities. Pharmacists, as highly accessible healthcare professionals, are uniquely positioned to play a preventive role in psoriasis management. From early recognition and referral to counselling

on lifestyle modifications, pharmacists can reduce the risk of flare-ups and complications, while improving patient quality of life.

Community pharmacists often serve as the first healthcare contact for people with skin concerns. Their role in education, medication optimisation, and long- term support is critical. By embedding preventative strategies into routine pharmacy practice, pharmacists can help patients take control of their condition and reduce the wider health system burden.

Strengthening the pharmacy role in psoriasis prevention

Expanding pharmacist services in psoriasis prevention requires investment in training, public awareness, and integration with dermatology and primary care teams. Pharmacists’ expertise in medicines, combined with their accessibility, positions them as vital allies in preventing flare-ups, reducing comorbidities, and supporting healthier lifestyles.

The path forward

Psoriasis is more than a skin condition ? it is a systemic disease requiring a proactive and preventative approach. Pharmacists, embedded within communities, have a crucial role in this shift. By combining early identification, medication counselling, lifestyle support, and comorbidity screening, pharmacy teams can significantly improve outcomes for people living with psoriasis.

Patients benefit from accessible advice, reduced stigma, and earlier intervention. Health systems benefit from reduced demand for secondary care. Ultimately, embedding psoriasis prevention into pharmacy practice ensures a future where fewer patients suffer avoidable flare-ups, complications, or diminished quality of life. But this approach needs the foresight and investment from health services including the likes of the Department of Health and HSE and is an example of the potential expanded roles of pharmacists that the Irish Pharmacy Union (IPU) is calling for ? with expanded services for pharmacy a part of the negotiations with the IPU and the Department of Health including the recent talks on funding, expanded roles of pharmacy, etc, in Ireland.

Communication and patient engagement in psoriasis care Effective pharmacist-patient communication is central to improving psoriasis outcomes. Beyond medicines counselling, trust and shared decision-making encourage adherence and empower patients. Practical strategies include active listening, open- ended questioning, plain language, teach- back, and non-verbal empathy.

Pharmacists can address non-adherence by simplifying regimens, offering reminder tools, and monitoring refill patterns. Shared decision-making ensures patients understand treatment steps, from topicals to biologics, and feel ownership of choices. Health literacy support such as using diagrams, demonstrating devices, and tailoring advice to culture and context further strengthens safe medicine use.

Real-world engagement includes topical application demonstrations, biologic injection training, lifestyle consultations, and comorbidity screening. Trust develops through continuity, remembering past discussions, and showing genuine concern. This long-term relationship positions pharmacists as reliable partners in managing a lifelong condition.

Evolving pharmacy practice in Ireland

The Irish healthcare system is undergoing significant reform through Sláintecare, which prioritises shifting chronic disease management into primary and community care. Pharmacists are increasingly recognised as central to this transition. Legislative changes, such as extended prescription validity, wider vaccination services, and the expansion of health screening have already increased the scope of pharmacy practice.

Looking ahead: The future of psoriasis prevention in pharmacy

Pharmacists are well positioned to take on an expanded preventative role in psoriasis care. For this potential to be fully realised, several steps are needed:

- Training and education: Pharmacy teams should be equipped with the latest clinical guidance on psoriasis, including new therapies and

monitoring requirements.

- Integration with other healthcare providers: Collaboration with GPs, dermatologists, and rheumatologists will ensure continuity of care and timely referral when needed.

- Policy and funding support: To maximise impact, pharmacists require recognition and investment in preventive service delivery.

Ultimately, embedding psoriasis- focused prevention into pharmacy practice will benefit patients, reduce pressure on secondary care, and align with national health priorities. This will hopefully be part of the Irish Health Service’s long promised and long overdue expanded roles for pharmacists.

Disclaimer: Brands mentioned in this article are meant as examples only and not meant as preference to other brands.

Written by Eamonn Brady MPSI (Pharmacist). Whelehans Pharmacies, 38 Pearse St and Clonmore, Mullingar. Tel 04493 34591 (Pearse St) or 04493 10266 (Clonmore). www.whelehans.ie. Eamonn specialises in the supply of medicines and training needs of nursing homes throughout Ireland. Email info@whelehns.ie