A clinical synopsis of the diagnosis, treatment, and management of haemochromatosis, a condition for which Ireland has one of the highest rates in the world

Introduction:

Haemochromatosis (HCM) is the most common inherited genetic disease in European populations 1, and Ireland has the highest rates in the world (on-in-83 at risk, one-in-five are carriers.2 The most common mutation leading to the disorder is in the HFE gene, accounting for about 80 per cent of cases, almost entirely in white populations. This gene codes for hereditary haemochromatosis protein.3 Individuals homozygous for this mutation (which is a substitution of a tyrosine for a cysteine at position 282 – C282Y) develop iron overload and the clinical consequences of such.4,5 Another variant (the substitution of a histidine for an aspartic acid – H63D) is also associated with HCM. There are non-HFE associated forms of the disease which can affect both white and non-white individuals, but these are rare. Several modifier genes can also impact the HCM phenotype.

HFE-associated HCM is caused by a deficiency of hepcidin, which is regulated in part by the hereditary haemochromatosis protein ( from the HFE gene). This restricts the passage of iron into the plasma. Hepcidin deficiency results in increased iron release from splenic macrophages and cells of the small intestine into plasma. Increased circulating iron levels lead to increased iron transport into cells, predominantly into hepatocytes, pancreatic cells, and cardiomyocytes, leading to iron overload in these areas in particular. Cellular iron toxicity due to iron excess leads to the formation of reactive oxygen species, which can cause organ damage.These outcomes can be prevented through therapeutic venesection.1

RISK FACTORS

The outcome for people with hereditary HCM depends on additional environmental and genetic factors, including sex, alcohol consumption, and blood loss. Male carriers homozygous for the HFE gene mutation display biochemical and symptomatic HCM to a greater degree than female carriers.

In a European study5 looking at C282Y homozygotes, documented iron-overload disease developed in 28.4 per cent of men and 1.2 per cent of women (although estimates vary from study-to-study). When this study began, 81.8 per cent of men and 55.4 per cent of women had increased serum ferritin levels, suggesting that biochemical penetrance is higher than clinical penetrance in HCM.3 Excessive alcohol consumption contributes to the progression of HCM symptoms: A nine-fold increase in cirrhosis has been reported in C282Y homozygotes who drink more than 60g of alcohol a day (a standard drink contains 10g). Consuming haemoglobin iron (ie, from red meat) is correlated with increased iron loading.1

SYMPTOMS

People with normal serum ferritin concentrations are unlikely to develop symptoms, and generally patients with

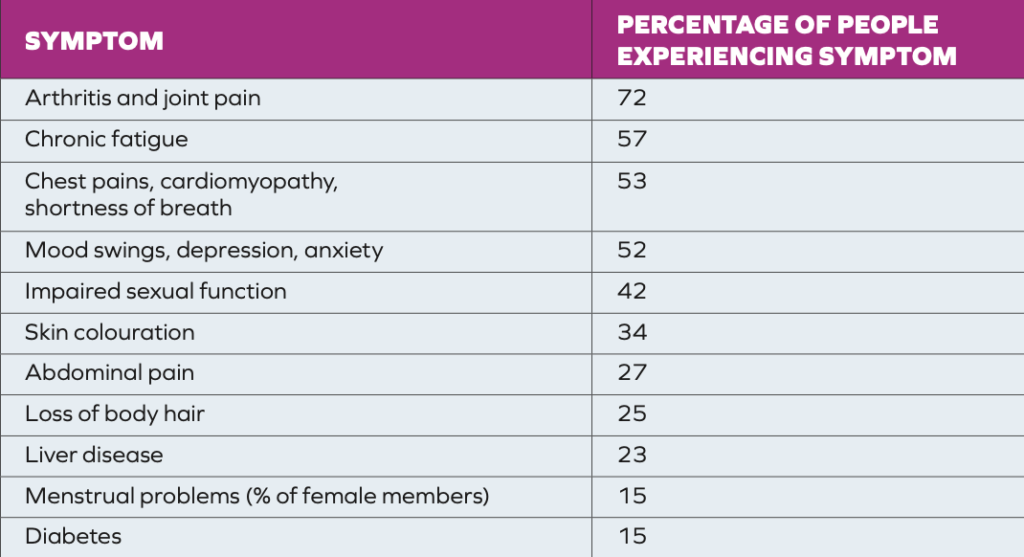

HCM are asymptomatic for many years.1,3 People with hereditary HCM may eventually present with abnormal iron tests, possibly with clinical symptoms.1 The most common symptom at the early stage is lethargy, with or without raised serum transaminase/ferritin levels. Extrahepatic manifestations include chronic fatigue, diabetes, arthropathy (most commonly in the hands, but can occur in all joints), mental health issues, osteoporosis, cardiomyopathy (rhythm disorders or heart failure), and hypogonadism (reduced sexual function).1,4 Dermatological signs include melanoderma (darkening of the skin), and nail changes. The main hepatic symptom is hepatomegaly (enlargement). Men display symptoms on average around the ages of 30-to-40, whereas women often do not have symptoms until around 40-to-50 years of age, or after the menopause.1,3 In contrast to other types of liver disease, cirrhotic livers in HCM are well functioning, with neither cellular insufficiency or portal hypertension, which explains why HCM patients are more likely to develop hepatocellular carcinoma rather than complications of liver failure. A survey of the members of the British Haemochromatosis Society showed the percentage of members experiencing various complications from iron overload (Table 1).

TABLE 1: Incidence of complications among members of the British Haemochromatosis Society4

DIAGNOSIS

Thankfully due to the widespread availability of genetic testing, many patients are now diagnosed before the symptoms manifest. Serum ferritin is not a reliable predictor because in early disease, it may not be elevated. Increased ferritin is also quite non- specific: It is observed in many conditions,

ie, alcoholism, metabolic syndrome, inflammatory syndrome, and diseases with cell necrosis.1 Serum iron and percentage saturation of transferrin are increased early and have a much better specificity than ferritin, although even with these other states may contribute to false positives or negatives. Generally, a persistent fasting serum transferrin saturation of more than 45 per cent is potentially an early sign of the disease and should be followed up with HFE genetic testing.1 Transferrin saturation is the ratio of the number of occupied iron binding sites to the total number of iron binding sites on plasma transferrin.3 Once diagnosis is established, first-degree family members should be genetically tested also. HCM symptoms develop slowly. It may not develop even when genetic mutations have been identified, but when it does, it usually progresses through four stages:4

- Stage 1: The genetic predisposition, but no other abnormality (gene positive).

- Stage 2: Iron overload, but without symptoms (gene positive, elevated transferrin saturation, and normal or elevated serum ferritin).

- Stage 3: Iron overload with early symptoms (gene positive, elevated serum ferritin, fatigue, and joint pain).

- Stage 4: Iron overload with organ damage, especially liver damage.

MANAGEMENT

Venesection

All international guidelines agree that excess iron should be treated with venesection (removal of blood) because clinical evidence shows that if this is done before the onset of cirrhosis and diabetes, there is a reduction in morbidity and mortality associated with HCM.1 The time to start treatment for HCM is recommended when the serum ferritin concentrations are above the upper limit of normal, however, the definition of these levels varies in different guidelines. Each 450ml of blood contains about 200mg of iron.4 Dietary modifications that modulate iron intake and bioavailability may affect levels of iron accumulation and also encourage active involvement and engagement with disease management.3

Diet

On average, healthy people absorb about 1-2mg of iron per day, but people with haemochromatosis absorb more than this. Although limiting some very high-iron foods, as well as foods that increase iron absorption can help, there is no need to cut out iron completely because it is an essential nutrient. Many foods with iron are also rich in other beneficial nutrients, so cutting out these foods could result in an unbalanced diet that lacks other nutrients.6

Iron is needed in the body for:

- Making haemoglobin in erythrocytes. uNormal brain function.

- Energy release from food.

- Making myoglobin.

- Immune function.

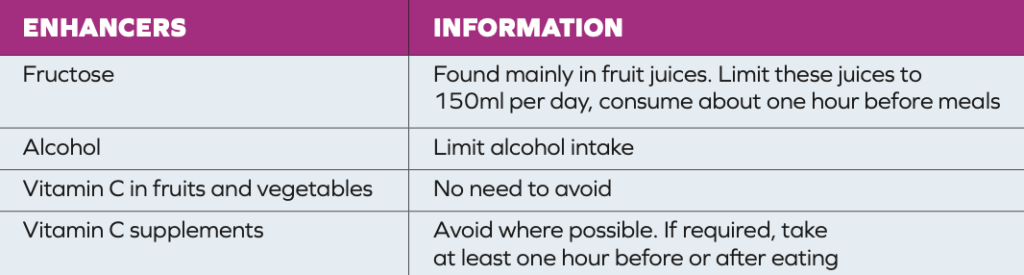

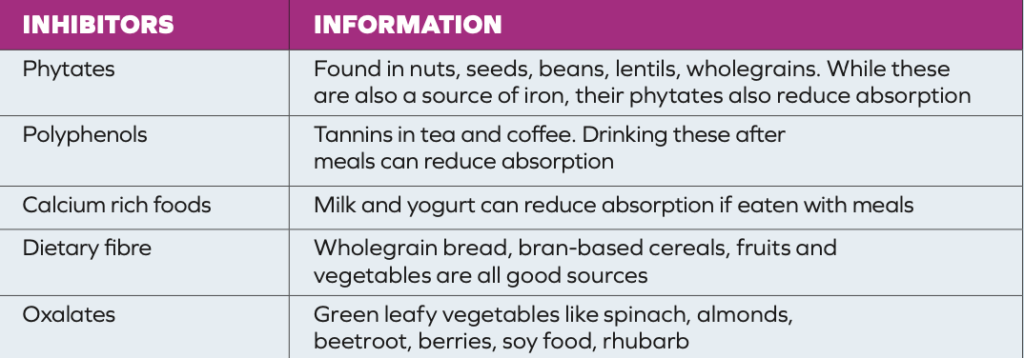

The recommended daily dose of iron for women pre-menopause is 16mg per day, and for women post-menopause and men, it is 11mg per day. Haem iron is found in meat, poultry and fish and is easily absorbed. Non- haem iron, found in eggs, fortified foods, and plant foods like spinach, whole grains, lentils, and nuts is more difficult to absorb. In HCM, it may be helpful to eat more foods that contain non-haem iron.3 Enhancers (Table 2) are foods/nutrients that increase the amount of iron absorbed by the body.6 Inhibitors (Table 3) can reduce the absorption of iron. Limiting haem iron foods, reducing enhancers and increasing the amount of inhibitors consumed with meals may reduce the number of venesection treatments required. In general, most people do not require iron supplementation unless they are shown to be deficient in iron. In the past, iron was recommended for many people with fatigue and general aches and pains. However, these symptoms (especially in older people) may be symptoms of iron overload.

People with HCM should avoid raw shellfish because this can be contaminated with Vibrio vulnificus. This bacteria thrives on iron, and can become more serious in people with HCM.

TABLE 2: Dietary enhancers of iron absorption

TABLE 3: Dietary inhibitors of iron absorption6

Alcohol

Iron overload due to haemochromatosis can lead to liver damage and cirrhosis. Even when there is no liver damage, limiting alcohol is still advised as it puts pressure on the liver and increases iron absorption. Some alcoholic drinks, especially cider, are in themselves a source of iron. In Ireland, the maximum number of standard drinks per week for men is 17, and for women is 11. However, in HCM, patients may be advised to reduce or avoid alcohol completely.

THE ROLE OF THE PHARMACIST

The clinical effect of hereditary HCM is increasingly recognised, but it is still important to spread awareness. Iron is a vital micronutrient, but a careful intake is required in this patient cohort. Some mechanisms behind the multi-organ disease that results from hereditary HCM are still not fully understood. Pharmacists are in a good position to promote patient education on the information we do have, referring for clinical assessment if symptoms of the disease are suspected, or advising on dietary and vitamin supplement choices in diagnosed cases. The Irish Haemochromatosis Association is an excellent resource for patients and family members and also offers brochures for pharmacies.

REFERENCES

1. Powell LW, Seckington RC, Deugnier Y. (2016). Haemochromatosis. The Lancet, 388(10045), 706-716.

2. Irish Haemochromatosis Association (2023). What is Haemochromatosis? Available at: https://haemochromatosis.ie/.

3. Brissot P, Pietrangelo A, Adams PC, De Graaff B, McLaren CE, Loréal O. (2018). Haemochromatosis. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 4(1), 1-15.

4. Irish Haemochromatosis Association (2016). Haemochromatosis Handbook. Available at: https://haemochromatosis. ie/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/ Irish-Haemochromatosis-Association- Handbook-2016.pdf.

5. Allen KJ, Gurrin LC, Constantine CC, Osborne NJ, Delatycki MB, Nicoll AJ, Gertig DM. (2008). Iron-overload– related disease in HFE hereditary haemochromatosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 358(3), 221-230.

6. Irish Haemochromatosis Association and Irish Nutrition and Dietetic Institute (2023). Diet and haemochromatosis. Available at: https://haemochromatosis.ie/wp- content/uploads/2023/04/ Diet-Haemochromatosis-Guide- Feb-2023.pdf.

Author: Dr Donna Cosgrove (PhD). Donna’s overall aim is to improve patient outcomes through education. After graduating with a BSc in Pharmacy, she returned to university to complete a MSc in Neuropharmacology.

This led to a PhD investigating the genetics of schizophrenia, followed by a postdoctoral research position in the same area. She has worked in hospital, research, and community pharmacy settings and is currently a community pharmacist in Galway and a clinical writer.