Eamonn Brady MPSI discusses atrial fibrillation, a ‘silent killer’

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common form of arrhythmia (heart rhythm problem). An arrhythmia is a heart rhythm problem of which there are many types. An arrhythmia can manifest itself as the heart rate being too quick, too slow or is an irregular manner.

Types of arrythmia include:

- Tachycardia: Fast heart rate of more than 100 beats per minute.

- Bradycardia: Slow heart rhythm below 60 beats per minute.

- Supraventricular arrhythmias: Arrhythmias manifesting from the atria (heart’s upper chambers).

- Ventricular arrhythmias: Arrhythmias manifesting from the ventricles (heart’s lower chambers).

- Bradyarrhythmias: Slow heart rhythms due to disease in the heart’s conduction system affecting the sinoatrial (SA) node, atrioventricular (AV) node or the His-Purkinje network.

AF is classed as a supraventricular arrhythmia, ie, it manifests from the atria. Atrial flutter is another atrial arrhythmia caused by one

or more rapid circuits in the atrium where heartbeats are faster than normal. Atrial flutter is usually more organised, meaning more regular than beats in AF. Atrial flutter can be a symptom of AF, or can occur without having AF.

Background to AF

AF is caused by irregular heart rhythm and (but not always) tachycardia (fast heart rate). AF is also referred to as AFib for short. While AF can case physical symptoms like tiredness, breathlessness and chest tightness or chest pain, most patients with AF experience no symptoms. Often, the only reason a patient knows they have is when it shows up during a regular checkup, or it is discovered due to another heart problem brought on by AF, ie, stroke.

Like hypertension or hypercholesterolemia, AF could be described as a silent killer; like these conditions, it is often symptomless yet significantly increases risk of potentially fatal heart problems like stroke and heart failure. AF increases the risk of up to stroke five-fold.

AF is managed with medication or procedures like an electrical cardioversion and once managed with appropriate treatment, will rarely cause serious or life-threatening problems.

Aetiology of AF

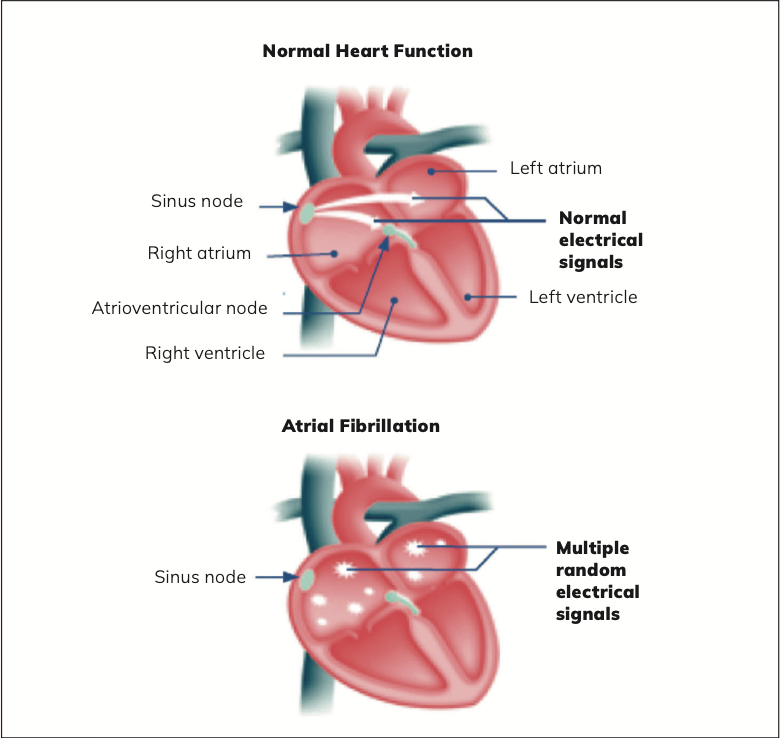

Instead of steady and regular electrical impulses from the sinus node in the right atrium that occurs when a person has normal heart function, with AF, electrical impulses from the sinus nodes fire irregularly and randomly. These disorganised impulses cause the atria to quiver or twitch (fibrillate) instead of a steady smooth beat. This means the atria cannot efficiently pump blood into the ventricles.

The loss of normal efficient pumping mechanism can reduce blood flow from the heart to the rest of the circulatory system especially if tachycardia occurs; not all patients with AF experience tachycardia (over 100 beats per minute). For many, AF is symptomless, but some patients can feel the physical sensation of the palpitations. The patient may experience paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, where AF comes and goes, but for others, AF occurs indefinitely, so the patient will have persistent or permanent atrial fibrillation unless treated. While AF in itself is not life-threatening, it is a major risk factor for blood clots that can lead to stroke.

Atrial flutter is a characteristic of AF where the atria beat regularly but faster than usual, meaning atria beat more often than the ventricles. In a patient with normal heart rhythm, there is a normal one-to-one ratio of atrial beats to ventricular beats. In patients with atrial flutter, there can be three or four atrial beats for every one ventricular beat.

Patients can experience atrial flutter without atrial fibrillation. Atrial flutter treatment is similar to atrial fibrillation, ie, medication to slow and regulate heart rate, cardioversion, and cardiac ablation.

Prevalence

AF has a prevalence of approximately 1 per cent in the overall population, but this increases to up to 10 per cent of people over 80. The risk of stroke varies significantly, ranging from 1 per cent to 15 per cent per year, depending on coexisting coronary risk factors such as age and presence of hypertension, hypercholesteremia, diabetes and smoking.

Causes of AF

- Hypertension.

- Myocardial infarction.

- Damaged heart muscle.

- Heart valve disease.

- Congenital heart disease.

- Pericarditis (inflammation of the pericardium, the protective sac surrounding the heart).

- Cardiomyopathy.

- Heart or other major surgery.

- Sick sinus syndrome (damage to the sinus node in right atrium).

Certain activities or lifestyle factors can trigger an episode of atrial

fibrillation, including binge drinking of alcohol, physical or mental

stress, obesity, excessive caffeine, smoking and illegal drugs (especially amphetamines and cocaine).

AF can sometimes be associated with other health conditions like asthma, diabetes, lung problems (lung cancer or pulmonary embolus) and severe infections, ie, pneumonia. There may be no obvious cause. Where there is no other heart or other risk factors, AF is known as ‘lone atrial fibrillation’. These patients are at lower risk of stroke.

Types of AF

The four subtypes of atrial fibrillation include paroxysmal, persistent, long- term persistent, and permanent atrial fibrillation. These four subtypes are classified by the frequency with which atrial fibrillation occurs and how well it responds to treatment.

Paroxysmal AF

This is characterised with a brief episode of AF known as a ‘paroxysm’ of AF. This brief episode of AF may be symptomless and go unknown

by the patient, or the patient can experience anything from mild to severe symptoms. It usually subsides within 24 hours but can last up to a week. Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation can repeatedly occur. Symptoms may go away without treatment but often, treatment is needed. Sometimes this type of atrial fibrillation alternates with a slower than normal heartbeat creating a phenomenon called tachybrady syndrome.

Persistent AF

Persistent AF is where the arrhythmia lasts more than a week. While it may stop on its own without intervention, most often treatment is needed to stop arrhythmias.

Long-term persistent AF

With this type of AF, arrhythmias longer than a year.

Permanent atrial fibrillation

Despite treatment with medication and other options, there are occasions where atrial fibrillation is resistant to treatment. This is known as permanent atrial fibrillation.

Symptoms

The patient may be symptomless but if symptoms occur, they range from mild to severe and can include:

- Breathlessness.

- Tiredness.

- Palpitations: The patient may feel the sensation the heart beating fast or irregularly.

- Light-headedness or dizziness.

- Chest pain or tightness.

The Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation surveyed 5,333 AF patients in 182 hospitals in 35 countries over 2003 and 2004 and found that 69 per cent of AF patients experienced symptoms related to AF at some stage since their diagnosis. Fifty-four per cent were asymptomatic at the time of the survey and the lowest symptom burden was reported in patients with permanent AF. Patients with AF and no symptoms are often detected to have atrial fibrillation during a physical examination or electrocardiogram (ECG).

Diagnosis

Echocardiogram

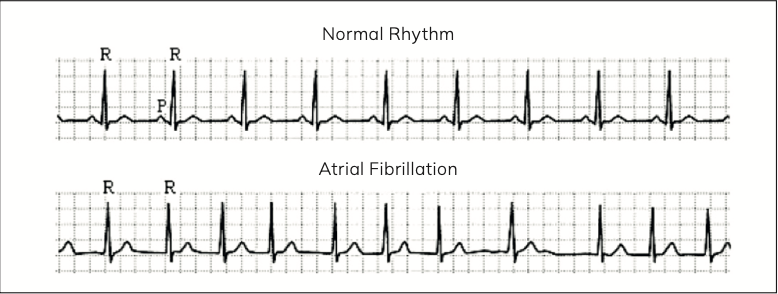

An electrocardiogram (ECG) checks the heart’s rhythm and electrical activity and confirms AF by recording the heart’s electrical signals. If the ECG is normal, but the clinician still suspects bouts of atrial fibrillation (paroxysmal atrial fibrillation), then a record of the heart rhythm over 24 hours will be needed to confirm. A Holter monitor can be used for this purpose. A Holter monitor is a type of portable ECG that the patient can wear at home and records electrical activity of the heart continuously over 24 hours or even longer.

An echocardiogram is a heart ultrasound scan that gives visibility of the heart’s structure and functioning.

An echocardiogram is considered the best diagnostic tool to diagnose AF. Echocardiographic predictors of AF are enlargement of left atrial, reduced function of the left ventricular and increased thickness of left ventricular walls.

Figure 2: ECG showing normal heart rhythm (top) and atrial fibrillation (bottom)

Reference: Journal of Biomechanics 41 (2008) 2515–2523

Blood tests

Blood tests cannot help diagnosing AF, but once a patient diagnosed with AF, they may be done to determine and rule out possible causes of AF, ie, diabetes, pulmonary embolus, infection.

Complications due to AF

AF is not in itself life-threatening, but it can cause serious complications, such as stroke and heart failure. The reason AF increases stroke risk is due to blood clots forming in the atria brought on by sluggish blood flow. Sluggish blood flow due to AF increases risk of these blood clots breaking off and travelling to the brain and blocking blood supply to parts of the brain, ie, stroke.

Congestive heart failure (CHF) is when the heart is not working adequately. It cannot meet the body’s need for blood because it is not pumping properly, and usually occurs because the heart muscle has become too weak or stiff to work properly. CHF is the leading cause of hospital admissions in the over-65 age group, accounting for 20 per cent of hospital admissions in this age group. In the case of AF, CHF is brought on by the heart not pumping properly. AF causes inefficiencies in the heart’s pumping mechanism, meaning the heart in unable to pump enough blood around the body, leading to peripheral oedema (especially in the lower legs) and lung congestion.

Risk of stroke

According to the Irish Heart Foundation, approximately 7,500 people have a stroke annually in Ireland, of which approximately 2,000 people die from stroke annually.

Rates of stroke in patients with AF averages 5 per cent a year; this is between two and seven times the stroke rate in those without AF. This increased risk of stroke is not solely due to AF; the risk increases significantly with the presence of coexisting cardiovascular risk, such as increasing age, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, etc. Prevalence of stroke in the general population in patients under 60 is less than 0.5 per cent and from 70 years onwards, the prevalence doubles with each decade.

The attributable stroke risk due to AF is approximately 1.5 per cent for patients aged 50-to-59 and it increases to 30 per cent for patients aged 80-to-89. Attributable stroke risk is higher in women due to AF than men. Some studies suggest this increased attributable risk in women is due to undertreatment with warfarin and other anticoagulants, though not all studies concur with this theory with one study of patients over 65 with recently diagnosed AF found that under-use of anticoagulants compared to men had no influence on increased stroke risk in women.

Stroke risk is increased with the following:

- Previous stroke or mini stroke.

- Damaged heart valve.

- Hypertension.

- CHF.

- Diabetes.

- Over 65 and especially over 75 years.

Treatment

Aims of AF management are to:

- Relieve symptoms, such as palpitations, tiredness, dizziness, and breathlessness.

- Prevent serious complications, such as stroke and CHF.

- Regulate heart rate.

- Treat the cause of AF where identifiable.

Weight loss added to guidelines

The new guidelines now include recommending weight loss for overweight or obese AF patients. Studies find that losing weight can reduce the health risks associated with or even reverse AF. It can also help lower blood pressure. High blood pressure is often associated with AF.

Medication

Medication used to slow the heart rate include:

- Beta-blockers (atenolol, metoprolol).

- Digoxin.

- Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (CCBs), ie, verapamil, diltiazem.

- Amiodarone (less often used due to risk of side-effects).

Rate control versus rhythm control

Trials over the last 50 years show that ‘rate control’ has better patient outcomes when compared to ‘rhythm control’ in AF patients, however there is no difference in terms of mortality in achieving ‘rate control’ versus ‘rhythm

The new guidelines now include recommending weight loss for overweight or obese AF patients

control’. Rate control is easier to achieve than rhythm control, all of which means the preferred initial aim of drug treatment for AF is rate control over rhythm control. The few exceptions to this are:

- New-onset AF: Within 48 hours.

- Patients with atrial flutter: Cardiac ablation is preferred to drug treatment.

- AF has a reversible cause, ie, it is due to other conditions like myocardial infarction and damaged heart muscle; the first treatment option is to control these conditions which in turn may reverse AF.

- If there is another specific reason that rhythm control is required to control rate, ie, constant and severe symptoms.

Beta blockers

Beta blockers such as atenolol and metoprolol are used to control ventricular rate in AF. Sotalol is not recommended due to poor patient outcomes, especially in patients with CHF and post MI.

Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (CCBs) Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (CCBs) such as diltiazem or verapamil as monotherapy are an option for ventricular rate control in AF. Dihydropyridine CCBs have the effect relaxing and widening blood vessels, as well as the additional effects of being rate-limiting, meaning they decrease myocardial contractility and heart rate. Non-dihydropyridine CCBs such as amlodipine and felodipine are not rate-limiting, so are not effective for AF. Verapamil is licensed for AF while diltiazem is not; however, diltiazem is used as an unlicensed indication by cardiac specialists for ventricular rate control in AF.

The choice of use of beta blockers versus dihydropyridine CCBs is based on type of symptoms, heart rate and the presence of other conditions.

Digoxin

Studies indicate digoxin is less effective than CCBs and amiodarone at controlling heart rate acutely, ie, need for fast rate control. Digoxin is more effective at controlling ventricular rate when the patients are at rest, so is reserved as monotherapy for AF patients with a sedentary lifestyle and for non-paroxysmal AF, especially those with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Digoxin is used when beta-blockers do not give sufficient rate control and where beta blockers are poorly tolerated and/or contraindicated.

Digoxin should be used in caution with older patients and patients with renal failure. Potassium levels must be monitored regularly to avoid digoxin toxicity due to hypokalaemia. Hypokalaemia is more of an issue for patients also prescribed diuretics, as diuretics, especially loop diuretics, reduce potassium levels. Hypokalemia can be a cause of digoxin toxicity because digoxin binds to the ATPase pump at the same site as potassium. With low potassium levels, digoxin more easily binds to the ATPase pump, thus increasing inhibitory effects of digoxin on heart muscle (increases force of contraction). This can lead to digoxin toxicity, which manifests as nausea and vomiting, anorexia, and neurological symptoms.

Digoxin has a narrow therapeutic index, which makes dosing more challenging. Digoxin interacts with many drugs, with its effect being increased by nephrotoxic drugs, including angiotensin-converting- enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin 2 receptor antagonists, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and ciclosporin. Digoxin is indicated for patients with CHF and reduced left ventricular function, so is an option where a patient has CHF and AF.

Combination drugs

A single drug may not be sufficient to control ventricular rate, so a combination of two drugs such as a beta-blocker, digoxin, or diltiazem is the next option. When ventricular function is reduced, the combination of a beta-blocker and digoxin is a preferred option. A beta blocker licensed for CHF should be used when ventricular function is reduced, ie, bisoprolol, carvedilol, nebivolol. If two drugs do not control rate, then rhythm control is the next option.

Drugs used to maintain sinus rhythm pre- and post- cardioversion For pharmacological maintenance

of sinus rhythm after an electrical cardioversion, a standard beta- blocker (ie, bisoprolol) is preferred. If a standard beta blocker is not effective, other options to maintain sinus rhythm post cardioversion include sotalol, flecainide, propafenone, amiodarone or dronedarone. The data to support the use of newer drugs like dronedarone is limited currently.

Amiodarone should be considered post-cardioversion where left ventricular impairment or heart failure is present. Amiodarone should be commenced four weeks before and up to 12 months after cardioversion to maximise the cardioversion success rate.

Amiodarone is considered the most

Digoxin should be used in caution with older patients and patients with renal failure

effective atrial arrhythmic drug,

however amiodarone has potentially irreversible side-effects (ie, ocular deposits, liver impairment, pulmonary toxicity). Therefore, amiodarone is mainly avoided as a long-term maintenance option. It is normally reserved for shorter courses (two-to-six months), particularly for patients who have been successfully treated for a secondary cause of AF or short-term post cardioversion.

Flecainide, sotalol and propafenone should be avoided in the presence of ischaemic or structural heart disease.

Paroxysmal AF

Treatment of paroxysmal AF is quite similar to longer-term AF. For paroxysmal AF, a standard beta blocker (ie, bisoprolol) is the first option to control ventricular rhythm. If a standard beta blocker is not effective, other options to maintain sinus rhythm post cardioversion are sotalol, flecainide, propafenone, amiodarone or dronedarone

Occasionally, in especially selected patients with infrequent bouts of symptomatic paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, normal rhythm can be restored using what is referred to as the ‘pill in the pocket’ method; the patient is trained to take oral flecainide acetate or propafenone to self-treat an episode of AF when it occurs, ie, they recognise symptoms like palpitations.

Cardioversion

If AF is recent or causing severe symptoms, a cardioversion is a good option to reinstate normal

heart rhythm and therefore control symptoms. A cardioversion involves using a small electric shock through electrodes (patches or paddles) placed on the chest while the patient in under a general anaesthetic. The electrodes are connected to defibrillator, which delivers shocks in a controlled manor to the chest.

The defibrillator monitors heart rhythm during the procedure and the clinician knows immediately once the procedure is done if the cardioversion is successful, ie, if normal heart rhythm has been restored. The procedure itself only takes five minutes, while the whole procedure, from being put asleep under a general anaesthetic to recovery, takes about 45 minutes. Cardioversion is done in hospital. Cardioversion is done as a day procedure, so the patient does not need to stay overnight in hospital.

Risks from cardioversion

As blood clots may develop within the atria due to slow or less consistent blood slow due to AF, a risk from cardioversion is that a thrombus (blood clot) breaks away from the atria as normal heart rhythm is restored during the cardioversion. This can lead to a blood clot traveling through the circulatory system, ie, thromboembolism.

A transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) may be undertaken prior to the cardioversion to check for clots in the atria; a TEE involves insertion an ultrasound probe inserted under sedation via the throat and oesophagus and the probes gives ultrasound images of the heart to show up any clots.

For this reason, anticoagulants such as warfarin or a NOAC are prescribed for most patients for at least four weeks before and after the cardioversion. The risk of thromboembolism is higher for patients who have had AF for more than 24 to 48 hours. Very early diagnosis of AF (within 48 hours) is very unlikely and even that is the case, organising a cardioversion with this time period is less likely, meaning anticoagulants are nearly always prescribed before and at least four weeks after a cardioversion. Many patients are prescribed anticoagulants long-term after a cardioversion.

There is no consistent agreement as to whether warfarin or NOACs are better to prevent thromboembolism before and after a cardioversion; neither appear superior in terms anticoagulant effect. NOACs offer the advantage of not having to monitor INR and consistent (less complicated) dosing, however patient compliance is more difficult to monitor with NOACs compared to warfarin (the INR identifies patient compliance with warfarin) meaning many clinicians still choose warfarin

as the anti-coagulant of choice for cardioversion due to the considerable importance of proper coagulation during cardioversion. Despite NOACs such as apixaban being increasingly used, European data shows that warfarin is still used as the anticoagulant of choice in over 65 per cent of patients in Europe, though this figure varies from country- to-country.

Other risks from cardioversion include a small risk of heart tissue damage from the electrical shocks, but this risk is extremely low due to the strict monitor of the current level used. There may be a small degree of burning of the skin on the site to which the patches are applied, but this is also rare.

Pharmacological cardioversion

Pharmacological cardioversion is done with oral or intravenous anti- arrhythmic drugs, including flecainide or amiodarone. Electrical cardioversion is preferred if AF has been present for over 48 hours.

Success rates of cardioversion for AF Cardioversion success rates for restoring normal heart rhythm from AF is over 90 per cent. Success rates is lower if AF is present for more than a few months. For this reason, cardioversion is recommended as soon as possible after AF presents. Success from cardioversion is lower if there is enlargement of the left atrium. A cardioversion may only maintain sinus rhythm for a few minutes, days, or weeks after the procedure. Recurrence rate of AF after cardioversion ranges from 70-to-85 per cent one-year post cardioversion, meaning antiarrhythmic drugs are often used long term after the cardioversion.

Other options to maintain sinus rhythm

Other options may be considered if cardioversion or anti-arrhythmic drugs are not successful, or if side-effects from medication are a problem.

Cardiac ablation

Cardiac ablation involves the using small burns or freezes to create some scarring on the inside of the heart to prevent conduction of abnormal electrical signals travelling from the atria to the ventricles. An ablation involves inserting and threading a small catheter via blood vessels in the groin to the heart, either to administer small burns to heart tissue using radiofrequency energy, or freezing to specific areas of heart tissue (micro ablation).

Risks from cardiac ablation include blood vessel damage, heart valve damage and blood clot risk. Major complications from ablation are reported in 6 per cent of ablation procedures worldwide, which is a reason it is reserved for more persistent cases. Cardiac ablation is more successful in the management

of paroxysmal AF, with more recent European and American guidelines pointing to the benefits of cardiac ablation in managing paroxysmal AF. Forty per cent of AF patients have co- existing congestive cardiac failure, and cardiac ablation appears to give good treatment outcomes when compared to other treatment options when

AF coexists with CHF. The efficacy of ablation techniques continues to improve, meaning the threshold

for when ablation continues to fall, meaning it is likely to be used more to treat AF in the future as success rates rise and complications fall.

Pacemaker

Clinical evidence rarely supports the use of a pacemaker for AF, however when bradycardia is an issue as part of AF, it may be considered if other treatments fail.

Stroke prevention

Traditionally, the two main anticoagulants for stroke and general clot prevention from AF were warfarin and aspirin. Warfarin has a better anticoagulant effect than aspirin and is used for patients with a high or moderate stroke risk. Warfarin reduces the stroke risk no matter how high the risk is by approximately two-thirds. Aspirin reduces stroke risk from AF by about 20 per cent and is reserved for lower-risk patients or where warfarin or NOACs are contraindicated.

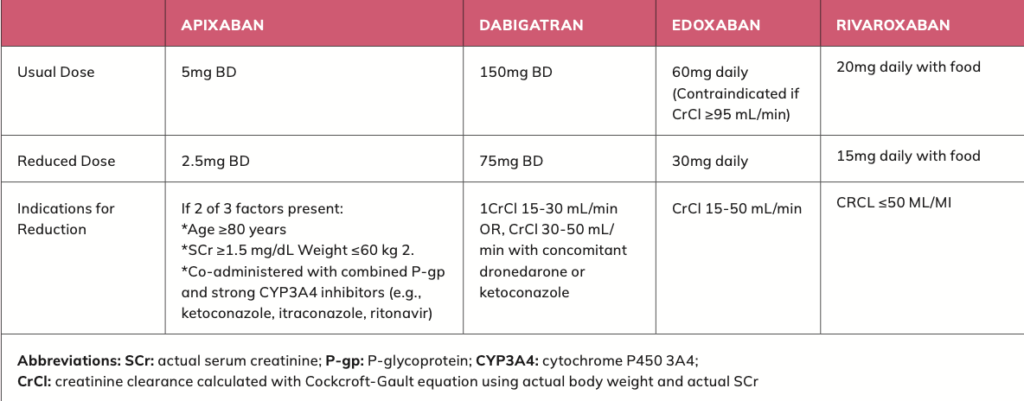

NOACs now anticoagulant of choice for stroke prevention in AF Novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs), also known as non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants, are the newest class of anticoagulant drug. NOACs are now the first choice for anticoagulant for stroke prevention in AF in worldwide guidelines, unless a patient has a mechanical heart valve or moderate-to-severe mitral stenosis (narrowing of the heart’s mitral valve).

NOACs include rivaroxaban, apixaban, dabigatran and edoxaban. NOACs are now first choice as evidence shows NOACs are safer than warfarin due to less risk of bleeding and are more effective than warfarin preventing blood clots. NOACs also have less drug and food interactions than warfarin. NOACs are contraindicated with impaired renal and hepatic function, and function should be checked prior to NOAC initiation and annually thereafter.

NOACs are at least as good as warfarin for the prevention of ischaemic stroke and thromboembolism elsewhere in the body. NOACs offer the additional benefit of reducing haemorrhagic stroke risk by 50 per cent. An ischemic stroke is a blood clot in an artery (and less frequently a vein) in the brain and account for approximately 87 per cent of all strokes. Haemorrhagic stroke is bleeding on the brain and account for approximately 13 per cent of strokes.

More evidence is emerging that NOACs should be used for patients even at very low risk of stroke from

AF, but more studies are needed before this recommendation becomes universal. NOACs are also considered an appropriate alternative to warfarin to prevent thromboembolism during and after cardioversion.

There has been more evaluation and evidence that NOACs are more effective versus warfarin for the prevention of stroke with non-valvular AF (ie, AF that is not caused by a heart valve problem) but less studies and evidence of their efficacy over warfarin for prevention of stroke with valvular AF (AF caused by a heart valve problem). However, evidence emerging in 2021 indicates that NOACs have a better efficacy of stroke risk benefit over warfarin for valvular AF. Warfarin is more effective than NOACs and still the anticoagulant of choice to prevent clot risk for patients with mechanical heart valves (with and without AF).

References on request

Written by Eamonn Brady MPSI (Pharmacist). Whelehans Pharmacies, 38 Pearse St and Clonmore, Mullingar. Tel 04493 34591 (Pearse St) or 04493 10266 (Clonmore). www.whelehans.net. Eamonn specialises in the supply of medicines and training needs of nursing homes throughout Ireland. Email info@whelehans.ie