INTRODUCTION

Eating a healthy diet throughout life is important — it helps to prevent malnutrition and many non-communicable diseases (NCDs). Changes in food production and the way we live have led to a shift in dietary patterns where we are now consuming more high-energy, fatty, sugary and salty foods, and not enough fruit, vegetables and dietary fibre like wholegrains.1

Many social and economic factors interact to shape individual dietary habits, including income, food prices, individual beliefs and preferences, traditions, and geographical and environmental influences. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), promoting a healthy food environment requires multiple stakeholders, including the Government, public and private sectors.2 It has been suggested that for previously-published nutrition guidelines in the United States, there was too much influence from food manufacturers, producers and special interest groups, resulting in some deviations from scientific nutrition recommendations.2

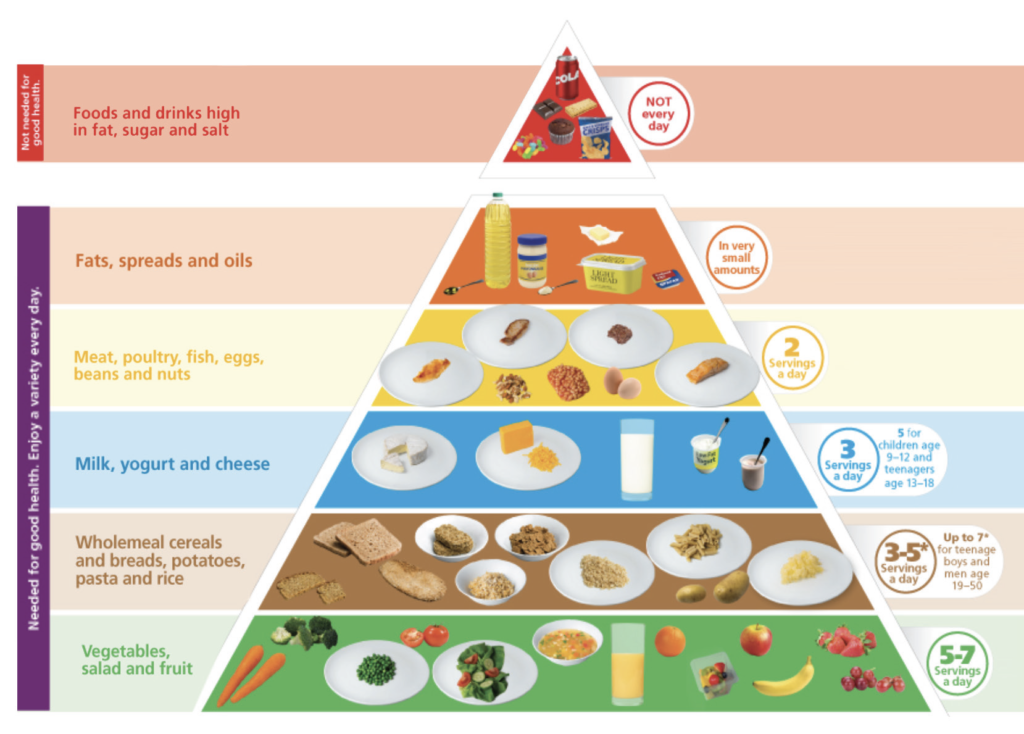

In Ireland, the current Food Pyramid was published by the Department of Health3 in December 2016 (see Figure 1). Subsequently, Irish healthy eating guidelines were published to complement this by the FSAI; a statutory, independent and science-based body advised by a scientific committee.4

A decreased life expectancy of between five-to-20 years is estimated in people who are obese, depending on the severity

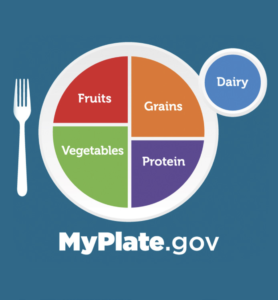

Some countries like the United Kingdom and the United States no longer use a food pyramid as a nutrition guide. In the UK, the Eatwell Guide5 has been used since 2016. In the US, MyPlate6 has been used from 2011 onwards (see Figure 2). These respective nutrition guides represent the different food types as the recommended relative proportions that should be eaten.

OBESITY AND OVERWEIGHT

At age 19, 80 per cent of men in Ireland are a healthy weight. By age 50, only 20 per cent are a healthy weight, and even less in over-50s. Fewer than 30 per cent of women over the age of 50 in Ireland are a healthy weight.7 The prevalence of obesity has increased in every country all over the world in the last 50 years and is the biggest current challenge in nutrition.8 A decreased life expectancy of between five-to-20 years is estimated in people who are obese, depending on the severity.

NCDs such as cardiovascular disease, cancers, and diabetes are the leading cause of mortality and disability worldwide, responsible for over 70 per cent of early deaths. The risk of these NCDs is increased by being overweight and obese, along with osteoarthritis, Alzheimer’s disease, and depression. Obesity itself has been declared by some groups to be a chronic progressive disease in itself, as opposed to just being a risk factor for other diseases. It has replaced tobacco consumption as the number-one lifestyle-related risk factor for premature death.

Although many current health recommendations are based on the fundamental cause of obesity being an imbalance between energy intake and expenditure, weight loss interventions to tackle the problem are not frequently successful long-term. Individual behavioural changes are more likely to be successful in the context of environmental and social influences.8

In human evolution, humans had to survive periods of under-nutrition, and as a result, selection pressure is likely to have preferred a genotype that favours overeating and low energy expenditure. It is only in recent decades that this has emerged as a problem, with the wide availability of inexpensive, mass-produced, high-fat, sugar-processed foods.

The technical revolution of the past century has also given rise to new transportation, computerisation and mechanisation, which have led to a decrease in energy demands, food-wise. These changes in food and lifestyle are an important contributor to the obesity epidemic; however, not everyone becomes overweight or develops obesity under these conditions.

Many factors influence BMI variability (see Table 1), and much of this may be even attributable to gene-environment or gene-behaviour interactions.

The prevalence of obesity in Ireland is about 23 per cent, higher than the OECD average of 19.5 per cent. The lowest of the OECD countries is in Japan, at <6%, and the highest in the US, at >35%.8 Looking at and identifying cultural and social factors in countries with low rates of overweight and obesity could help with this issue in countries with higher rates.

BMI (body weight in kg divided by height in metres squared) is the most widely used criteria for classifying obesity.9 Waist circumference (WC) is an important additional measure in many clinical and research settings and gives an indication of abdominal adiposity. The presence of this type of fat is associated with metabolic dysregulation, and predisposes people to cardiovascular disease and other related conditions. A WC >37 inches (94cm) for men or >32 inches (80cm) for women (in European populations) indicates an increased risk of CVD.

HEALTHY EATING GUIDELINES IN IRELAND

| Biological Factors | Environmental and Societal Factors |

| Adipose tissue expandability and distribution | Eating culture |

| Brain and central reward system | Economic systems |

| Brown fat | Food environment |

| Genetics and epigenetics | Food marketing |

| Inflammation | Policies |

| Insulin resistance | Shift work |

| Medications | Smoking status |

| Mental health and addiction | Social media |

| Microbiota | Stress |

| Neurocircuits of appetite and satiety regulation | Transportation |

| Sleep | TV and computer games |

| Weight cycling (unintentional loss/gain) | Workplace |

In 2019, the Food Safety Authority of Ireland (FSAI) published updated healthy eating guidelines and food pyramid.10 According to the FSAI, it combines international best practice with up-to-date Irish research to ensure the advice meets the dietary needs of the Irish population. Advice across four age groups from five to 51+ years is provided, aiming to protect people against diet-related illness such as heart disease, cancer, obesity and diabetes; all big contributors to ill health in Ireland.

Top tips for healthy eating in this guide7 include:

- Enjoy a variety of food, choosing the right amounts from each food group.

- Find enjoyable ways to be physically active every day.

- Be aware of serving sizes (a portion size reference guide specifically describes appropriate sizes using either a 200ml cup, the palm of your hand, or your thumbs as a measure).

- Eat plenty of different coloured vegetables, salad and fruit — different colours provide different nutrients (see Figure 3).

- Healthy carbohydrates (wholemeal breads, cereals, potatoes, pasta, boiled rice) provide calories to maintain a healthy weight — follow portion size recommendations.

- Choose low-fat dairy (milk, yogurt and cheese).

- Choose lean meat, poultry and fish (oily is best). Eggs, peas and legumes are good alternatives.

- Use polyunsaturated/monounsaturated spreads and oils sparingly. Reduced fat spreads are preferable.

- Bake, steam boil or stew instead of frying.

- Limit biscuits, snacks, and confectionery: These are high in calories, sugar, and salt.

- Limit salt intake — avoid adding salt when cooking or at the table.

- Drink plenty of fluids. Water is the best.

- Eat oily fish once a week to meet the vitamin D RDA.

- Whole fruits and vegetables are better than juicing because the fibre makes them more filling and reduces overeating generally.

- Avoid eating burnt starchy foods like potatoes, root vegetables and bread, due to the potential presence of the probable carcinogen acrylamide.

The importance of physical activity for health is specifically emphasised, as well as the importance of adequate vitamin D intake at Ireland’s latitude.

The FSAI guidelines7 also recommend taking these factors into account when using the food guide and pyramid:

- Body size.

- Activity level (Table 2 shows estimated energy requirements in different age groups of people who are moderately active).

- Age (younger people need more for growth and development).

- Gender (males need more than females, largely due to their body size).

- Look at the nutrition label of the food (visual examples are provided in the guide).

| Group | Calories |

| Girl (5-12 years) | 1,400-2,000 |

| Boy (5-12 years) | 1,400-2,200 |

| Teenage Girl (13-18 years) | 2,000 |

| Teenage Boy (13-18 years) | 2,400-2,800 |

| Adult Female (19-50 years) | 2,000-2,200 |

| Adult Male (19-50 years) | 2,400-2,800 |

| Older Female (51+ years) | 1,800 |

| Older Male (51+ years) | 2,200-2,400 |

MAIN ESSENTIAL VITAMINS AND MINERALS

Most people consume enough vitamins and minerals through a varied and balanced diet, although some may need supplements. The following vitamins and minerals11 are of particular importance for health:

- Vitamin A: Immune function, vision, healthy skin and nose. Beta-carotene is also metabolised to vitamin A.

- Vitamin B1 (thiamine): Energy metabolism, nervous system.

- Vitamin B2 (riboflavin): Skin, eyes, nervous system, energy metabolism.

- Vitamin B3 (niacin): Energy metabolism, nervous system, skin.

- Vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid): Energy metabolism.

- Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine): Use and storage of energy from protein and carbohydrates, formation of haemoglobin.

- Vitamin B7 (biotin): Fatty acid manufacture.

- Folate and folic acid (also known as vitamin B9): Formation of erythrocytes, reduction of neural tube defects in unborn babies.

- Vitamin B12 (cobalamin): Formation of erythrocytes, nervous system, folate metabolism.

- Vitamin C (ascorbic acid): Healthy skin, blood vessels, bone and cartilage; wound-healing.

- Vitamin D: Regulation of calcium and phosphate levels.

- Vitamin E: Skin, eyes, immune function.

- Vitamin K: Blood-clotting, wound-healing.

- Calcium: Bones and teeth; muscle function (contraction of striatal muscle); blood-clotting.

- Iodine: Synthesis of thyroid hormones, which maintains the metabolic rate.

- Iron: Manufacture of haemoglobin and myoglobin.

- Chromium: Carbohydrate, lipid, and protein metabolism.12

- Copper: Production of erythrocytes and leukocytes, infant growth, brain development, immune system and bones.

- Magnesium: Energy metabolism, parathyroid gland function (which regulates calcium levels).

- Manganese: Required as a cofactor for many enzymes, including metabolism.

- Molybdenum: Required as cofactor for DNA repair and replication processes.

- Phosphorus: Bones, teeth, energy metabolism.

- Potassium: Electrolyte for fluid balance, nerve function, muscle function (especially cardiac).

- Selenium: Immune function, reproduction.

- Sodium chloride: Both these minerals are required to maintain fluid balance. Chloride also aids digestion.

- Zinc: Creation of DNA, growth of cells, building proteins, healing damaged tissue, healthy immune system.13

According to the FSAI, it combines international best practice with up-to-date Irish research to ensure the advice meets the dietary needs of the Irish population

Donna Cosgrove graduated with a BSc in Pharmacy from the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland. She then returned to university to complete a MSc in Neuropharmacology, which led to a PhD and further research investigating the genetics of schizophrenia. Over the years Donna has worked in hospital, research and community pharmacy settings, but currently works as a community pharmacist in Galway and as a clinical writer.

References

1. World Health Organisation (2020). Healthy Diet Factsheet. Available https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet.

2. Heid M (2016, January). Experts Say Lobbying Skewed the US Dietary Guidelines. Time Magazine. https:// time.com/4130043/lobbying-politics-dietary-guidelines/.

3. safefood (2022). The Food Pyramid. Available https://www. safefood.net/healthy-eating/ guidelines/food-pyramid.

4. Food Safety Authority of Ireland (2020). About Us. Available https:// www.fsai.ie/about_us.html.

5. United States Department of Agriculture — MyPlate (2011). Graphics. Available https://www.myplate.gov/ resources/graphics.

6. Public Health England (2016). The Eatwell Guide. Available https://www. gov.uk/government/publications/the-eatwell-guide.

7. The Food Safety Authority of Ireland (2019). Healthy eating, food safety and food legislation: A guide supporting the Healthy Ireland Food Pyramid. Available https://www.fsai.ie/science_and_ health/healthy_eating.html.

8. Blüher M (2019). Obesity: Global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 15(5), 288-298.

9. Hruby A, & Hu FB (2015). The epidemiology of obesity: A big picture. Pharmacoeconomics, 33(7), 673-689.

10. The Food Safety Authority of Ireland (2019 January 28). Updated Healthy Eating Guidelines Guide to Improve Nation’s Diet (Press Release). https://www.fsai.ie/news_centre/ press_releases/healthy_eating_ guidelines_28012019.html.

11. National Health Service (2020). Overview — Vitamins and Minerals. Available https://www.nhs.uk/ conditions/vitamins-and-minerals/.

12. National Institutes of Health Dietary Supplements (2022). Chromium — Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. Available https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/ Chromium-HealthProfessional/.

13.Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health (2022). The Nutrition Source — Zinc. Available https://www. hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/ zinc/#:~:text=Zinc%20is%20a%20 trace%20mineral,supporting%20a%20 healthy%20immune%20system.