Headaches can have a big impact on quality of life and functioning, with the most common primary types being tension, migraine, and cluster, writes Donna Cosgrove MPSI

The cause of primary headaches is still not well understood. Secondary headaches arise from underlying causes, eg, medication overuse, raised intracranial pressure, or infection.1 The majority of headaches are primary, and serious causes of secondary headaches are unusual.2 Headaches can have a significant impact on quality of life and functioning. The most common primary headaches include tension-type, migraine, and cluster headache. Tension-type headache is the most common primary headache disorder with a mean global lifetime occurrence of 42 per cent. The global prevalence of migraine is 10 per cent in men and 22 per cent in women; with chronic migraine affecting two per cent of the population. When starting acute treatment, patients should be advised about the risk of developing medication overuse headache (MOH), discussed further below.3

Diagnosis

A headache diary (for a minimum of eight weeks) can aid with the diagnosis of primary headaches.1 The following information is useful to record:

- Frequency, duration, severity of headaches;

- Associated symptoms;

- Medications taken to relieve symptoms, their effectiveness;

- Possible causes;

- Relationship of headaches to the menstrual cycle.

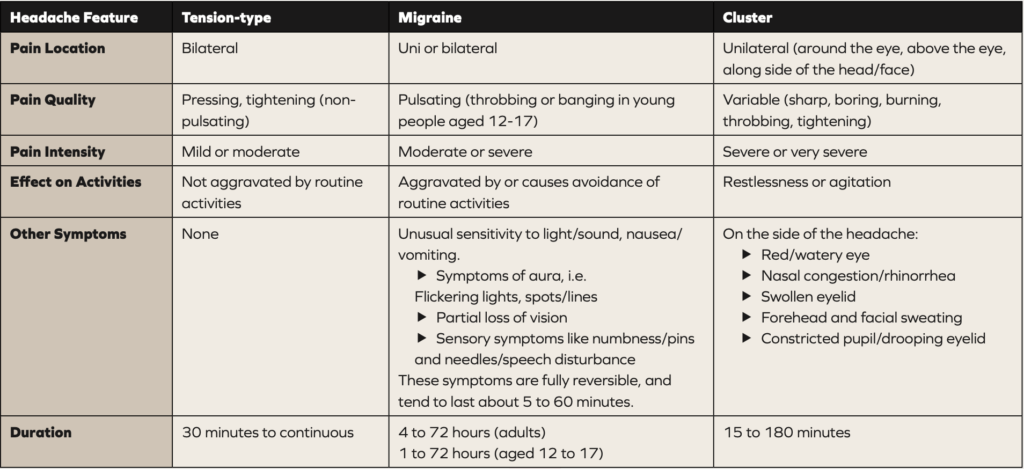

Table 1 below, adapted from the NICE guidelines, describes the features associated with the most common types of headache.

The temporal pattern of a headache can help with differentiating a primary and a secondary headache.2 A sudden onset headache, ie, reaching maximum intensity within five minutes (‘thunderclap’ headache), has the greatest probability of a secondary precipitant. If a headache evolves over days and weeks with associated systemic and focal neurological features, there is increased probability of a secondary cause. A recurrent episodic headache, in isolation, is likely just a primary headache disorder.

Some people experiencing headaches can be anxious about the presence of a brain tumour. Evidence indicates that, outside of an emergency setting, the risk of finding a serious issue from imaging patients with isolated headaches and a normal neurological examination is comparable to the risk of finding a serious issue in people who have no headache. There is also the potential for uncovering incidental findings (in 6 to 15 per cent of cases), which may not need any further management, but this can increase anxiety and also affect insurance premiums for the patient.

Table 1. Headache features according to headache type (1).

Cluster headache

The trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias are a group of headache disorders that are uncommon, and therefore are often misdiagnosed.2 They are primary headaches with a common clinical presentation consisting of trigeminal pain with autonomic signs, which may include lacrimation, rhinorrhoea, and miosis.4 Cluster headaches are one type of these. One of the most characteristic features of cluster headaches is restlessness,2 eg, patients typically walk up and down or rock to and fro, unlike people with migraine who can be motion sensitive and tend to remain still. For acute treatment of cluster headaches, oxygen, and/or a subcutaneous or nasal triptan are recommended in NICE guidance. Paracetamol, NSAIDs, opioids, or oral triptans are not appropriate to use in cluster headaches. Verapamil may help as prophylactic treatment1 although the doses used in cluster headache prevention can be higher than those used to treat cardiac disorders. Cardiac rhythm disturbances can result, and are neither dependent on the dose or the length of treatment. The British Association for the Study of Headache (BASH) recommends an ECG to be done at baseline, after each dose increase, and once every six months at a stable dose.3 Any prophylactic treatment should be tried for at least three months at the maximum tolerated dose before deciding whether it is effective or not.3

Few RCTs have been performed in pharmacological prevention of cluster headaches. Agents like lithium, topiramate, and gabapentin are used in clinical practice, but this is largely based on clinical experience rather than research evidence.1

Medication overuse headache

This type of headache most commonly occurs in people who are taking medication for a separate, primary disorder.1 Patients need to be advised that restricting acute headache medications to no more than two days in a week minimises the potential of developing MOH.2 Overuse of triptans can cause MOH faster and with fewer doses compared with analgesics: evidence shows that the average interval between first use and daily MOH was 1.7 years for triptans, and 4.8 years for analgesics. MOH is possible in people whose headache developed or worsened while they were taking triptans or combination analgesics for 10 days or more per month; or paracetamol, aspirin, or an NSAID (alone or in combination) for 15 days or more per month, over a three-month period.1 The NICE guidelines advise withdrawing the overused medication, stopping completely for one month. If repeated unsuccessful attempts at stopping have been made, referral is required.

The headache symptoms can become much worse in the short term, which is obviously difficult for many people. Withdrawal headache usually lasts from about two to 10 days after complete cessation of overused medication2 and gradually improves, although this can take up to 12 weeks. If there is any underlying primary headache, this can be treated prophylactically in addition to withdrawing the overused medication. NICE guidelines suggest the use of steroids might aid withdrawal, if appropriate.1 However, both the SIGN guidelines and the BASH guidelines specifically do not recommend the routine use of prednisolone in the management of MOH.2,3 People with MOH should not usually be admitted as inpatients for treatment, as outpatient medication withdrawal is as effective as inpatient treatment.2

Migraine

Chronic migraine (headaches for 15 or more days per month for three months) is linked with reduced quality of life, and increased anxiety, depression, and chronic pain.2 Migraine can be so disabling that even modest improvements in severity or frequency can be of huge benefit to the patient. In trials assessing migraine treatments, a reduction in severity or frequency of 30-50 per cent is considered to be a successful outcome.3 Peak prevalence is around the age of 40, with a median frequency of one to two attacks per month.

The NICE guidelines recommend combination therapy with an NSAID (or paracetamol) and oral triptan as first line acute treatment for migraine.1 A nasal triptan can be used in preference to an oral one. Monotherapy with an oral triptan, aspirin (900mg) or paracetamol can be recommended if monotherapy is preferred. The Scottish SIGN guidelines recommend aspirin 900mg, or ibuprofen 400mg (or 600mg) as first line treatment for patients with acute migraine.3 Lack of response to one triptan does not predict response to other triptans, so an alternative may be effective.2 An antiemetic might be required, eg, metoclopramide, prochlorperazine, or domperidone. Adding an antiemetic to an acute treatment improves efficacy unrelated to nausea.2 Antiemetics reduce nausea and vomiting, but also improve gastric motility and drug absorption.

If prophylactic treatment is required, topiramate or propranolol are options1,3 depending on the risks and benefits for each patient, which should be discussed. The potential benefit of migraine reduction in women must be balanced with the impact of topiramate on potential pregnancies and risk of reduced hormonal contraceptive efficacy. Amitriptyline is another option for prophylactic treatment, but the evidence is still not definitive. The need for any migraine prophylaxis medication should be reviewed after six months. Additional medications suggested for pharmacological prevention of migraine in the SIGN guidelines include amitriptyline, candesartan, sodium valproate, and botulinum toxin A.3 Calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibodies such as erenumab, after consultation with a specialist, are recommended in patients who have not had success with oral migraine prophylactic treatments.

In terms of non-pharmacological management, there is evidence to recommend a course of up to 10 sessions of acupuncture over five to eight weeks for prophylactic treatment, and the vitamin riboflavin (400mg once daily) may help reduce recurrence.1

Menstrual-related headaches usually occur between two days before and three days after the start of menstruation. For women with predictable menstrual related migraine, taking frovatriptan (twice daily) or zolmitriptan (two or three times daily) on the expected migraine days is an option if standard acute treatment is not sufficient.1,3 Women who experience migraine with aura have an increased risk of stroke, while use of the oestrogen contraceptive pill is also associated with increased risk of stroke.2 Consequently, alternative contraceptive methods are advised for women with migraine with aura.

Tension headache

Aspirin, paracetamol or an NSAID are options for acute treatment for a tension-type headache.1 As with migraine, there is evidence to recommend a course of up to 10 sessions of acupuncture over five to eight weeks for prophylactic treatment.

When to refer

People presenting with the following should be assessed and referred if necessary:1

- Worsening headache with fever;

- Sudden-onset headache reaching maximum intensity within five minutes;

- New-onset neurological deficit;

- New-onset cognitive dysfunction;

- Change in personality;

- Impaired level of consciousness;

- Recent (typically within the past three months) head trauma;

- Headache triggered by cough, valsalva (trying to breathe out with nose and mouth blocked), or sneeze;

- Headache triggered by exercise;

- Orthostatic headache (headache that changes with posture);

- Symptoms suggestive of giant cell arteritis (inflammation of the arteries, giving rise to headache, visual disturbances, and jaw claudication);

- Symptoms suggestive of acute narrow angle glaucoma;

- Significant change in the person’s usual headache characteristics.

- Psychological interventions like CBT are widely recommended for people with chronic painful disorders, including headaches. These types of interventions are useful for treatment of mood disorders, which are often comorbid with headache disorders, but a trial assessing the impact of psychological interventions on headache outcomes alone is needed.

References

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2021). Headaches in over 12s: Diagnosis and Management [CG150]. Available at www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg150

The British Association for the Study of Headache. (2019). National Headache Management System for Adults 2019. Available at www.bash.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/01_BASHNationalHeadache_Management_SystemforAdults_2019_guideline_versi.pdf

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. (2023). SIGN 155: Pharmacological Management of Migraine. Quick Reference Guide. Available at www.sign.ac.uk/media/2066/sign-155-qrg-2023-update-0-2.pdf

Benoliel, R. (2012). Trigeminal autonomic cephalgias. British Journal of Pain, 6(3), 106-123.