Donna Cosgrove PhD MPSI looks at the range of eye conditions that typically present in the pharmacy

As people get older, they are at greater risk for common eye diseases and conditions, including age-related macular degeneration (AMD), cataracts, glaucoma and dry eyes. While cataracts are treated with surgical intervention and glaucoma with prescription medication, there are products available over-the-counter to treat dry eyes and potentially help with AMD.

Dry Eyes

When a person does not produce enough quality tears to lubricate and nourish the eye, dry eye occurs. Tears are required to maintain the health of the eye, especially the anterior surface, and to provide clear vision.1 The act of blinking spreads tears across the cornea, which provides lubrication, reduces the risk of eye infections and washes away foreign matter in the eye. This keeps the surface of the eyes smooth and clear. Excess tears flow into drainage ducts in the inner corners of the eyelids, which drain into the back of the nose. Dry eye is a common and often chronic problem, particularly in older adults and can occur when tear production and drainage are not in balance.

When dry eye occurs, this is due either to not enough tears being produced, or else the tears are not good quality.

Inadequate amount of tears: Tear production tends to reduce as we age and can be caused by various medical conditions, or as a side effect of certain medicines (see list of ‘Medications that may cause dry eyes’). Environmental conditions can also decrease tear volume by increasing the rate of tear evaporation. When the normal amount of tear production decreases or tears evaporate too quickly from the eyes, symptoms of dry eye can develop.

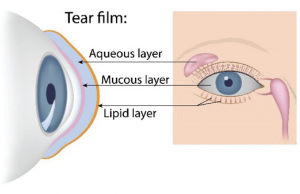

Poor quality of tears: Tears are made up of oil, water and mucus (Figure 1). Each of these layers protects and nourishes the eye. The smooth oil layer helps prevent evaporation of the water layer, while the mucin layer allows uniform distribution of the tears over the eye surface. If the tears evaporate too quickly or do not spread evenly over the cornea due to deficiencies with any of the three layers, dry eye symptoms can develop. The most common form of dry eyes is due to inadequate amount of the water layer of tears. This condition, called keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS), is also referred to as dry ‘eye syndrome’.

Mild or moderate cases of dry eye can be treated with tear substitutes, designed to mimic the tears produced in the eye. The underlying mechanism of symptomatic improvement with tear supplementation is still poorly understood. It has been proposed that improvements are due to the increased tear volume, improved tear stabilisation, reduced tear osmolarity, a dilution of inflammatory biomarkers, or a combination of these.3 Hydrogel polymers, such as those containing hypromellose (also called hydroxypropyl methylcellulose) or carbomer are effective for treating mild cases of dry eye. Hypromellose is frequently recommended as first-line, but to achieve adequate relief of symptoms, use may be required up to hourly. In these cases, more viscous products may be required, ie, carbomer 980, which binds moisture to the ocular surface, increasing the time for which moisture is retained. Carboxymethylcellulose drops are often considered if the hydrogel polymer products do not provide enough relief. In more severe cases or if symptoms are chronic, it may be necessary to use a lubricant with viscosity-increasing properties, such as sodium hyaluronate. Hydroxypropyl guar products increase in viscosity on contact with the ocular surface, forming a bio-adhesive gel. This mimics the mucous layer of the tear film, increasing aqueous retention. These products may be beneficial in mucous and aqueous deficiency. Preservative-free eye drops are available for people who wear soft contact lenses, and for those whose eyes are irritated by eye drops containing a preservative. Eye ointment is also available — research suggests a superior long-lasting effect compared with aqueous based ocular lubricants.

Vitamins A, C and E are thought to maintain healthy cells and tissues in the eye…

Lifestyle changes can improve the symptoms of dry eyes, such as use of humidifiers, stopping smoking, taking regular breaks from the computer to encourage blinking, and increasing dietary omega-3 fatty acid intake.

Age-related macular degeneration

AMD is the term given to ageing changes without any other obvious cause that occur in the central area of the retina (macula). AMD is painless but leads to the gradual impairment of vision.4 It can sometimes cause a rapid reduction in vision. It predominantly affects the central vision, which is used for reading and recognising faces. AMD is more common with older age, family history of AMD, smoking, hypertension, BMI of 30kg/m2 or higher, diet low in omega 3 and 6, vitamins, carotenoid and minerals, a diet high in fat, and lack of exercise.

There are two forms of AMD:5

Dry AMD: This causes central vision to become dimmer, and as the disease progresses, distorted. This is the most common form of AMD (90 per cent). The cells of the macula at the back of the eye become thinner and less efficient as we age. These cells lose lutein, a pigment essential to good eyesight. AMD is an acceleration of the natural ageing process at the back of the eye. Dry AMD cannot be treated, but taking lutein supplements, following a healthy diet and lifestyle with plenty of exercise and using good UV protective sunglasses can stabilise the progression of the condition.

Wet (neovascular) AMD: Abnormal blood vessels (in the choriocapillaris) behind the retina start to leak, which causes a drop in oxygen supply to the cells in the macula. The body responds by generating more abnormal (fragile) blood vessels and scar tissue. This process causes permanent vision loss to the central visual field. Unlike dry AMD, wet AMD causes rapid vision loss and requires treatment. Wet AMD in particular is thought to have strong genetic link, so if a family member has had wet AMD, it is a good idea to take a lutein supplement, follow a healthy diet and get plenty of exercise. Wet AMD does not develop suddenly; dry AMD usually occurs first, although the individual may not have been aware of it.

Wet AMD is treated by a specialist ophthalmologist using either photodynamic therapy, laser photocoagulation, or injections which prevent the formation of scar tissue and promote better healing at the macula. Anti-VEGF injections (ie, aflibercept, bevacizumab, ranibizumab) are given directly into the eyes. This prevents worsening of vision in 90 per cent of cases and improves vision in 30 per cent.6 These drugs bind to circulating vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF) and inhibit their activity. This decreases the proliferation of the fragile blood vessels in the choriocapillaris.

Vitamins A, C and E are thought to maintain healthy cells and tissues in the eye. More recently, interest has grown in another antioxidant, lutein, and a similar substance, zeaxanthin. Both are yellow plant pigments (ie, the yellow and orange in peppers, sweetcorn and saffron). Green leafy vegetables such as kale, spinach and broccoli also have high levels of lutein.7 Macular pigment is made up of three carotenoids: Lutein, zeaxanthin and meso-zeaxanthin. Meso-zeaxanthin is not typically found in diet, but has been identified in some fish species. It is thought to be formed at the macula by conversion from lutein, but the mechanism for this has not been confirmed.8 Antioxidants present in the retina (vitamin C, vitamin E, carotenoids, selenium and zinc) may prevent cellular damage by reacting with free radicals produced in the process of absorbing light.9 Dietary supplements are available, with varying combinations of these antioxidants and carotenoids. Multiple research studies have been performed to examine the effect of supplementation on macular degeneration. The Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) investigated the use of vitamin C 500mg, vitamin E 400 IU, beta carotene 15mg and zinc 80mg in the progression of macular degeneration. Results were positive in some groups, with patients experiencing a modest delay of 20-to-25 per cent in progression to advanced AMD at seven-year follow-up.4

A separate study published in 20168 that included 49 patients evaluated the effect of once-daily oral macular pigment supplementation in eyes with retinal pathology after six months. Supplementation consisted of 10mg lutein, 2mg zeaxanthin, and 10mg meso-zeaxanthin (Macushield). Results showed an increase in the mean macular pigment density, and significant improvement in glare disability and low-contrast sensitivity (the ability to distinguish an object from its background). The authors suggest that these findings warrant further investigation in larger studies with a longer follow-up period. The effects and benefits of each individual component in the supplements on AMD progression is unclear, as a combined supplement was used.4 The Meso-zeaxanthin Ocular Supplementation Trial (MOST) AMD study10 was conducted to examine the effect of sustained supplementation with carotenoids on visual function and disease progression. Forty-seven individuals completed the study to the 36-month follow-up point. Findings indicate that the inclusion of meso-zeaxanthin in a supplement formulation confer benefits in terms of macular pigment increase, and in terms of enhanced contrast sensitivity in subjects with early AMD. Although macular pigment increased after supplementation of all the carotenoids examined (lutein, zeaxanthin and meso-zeaxanthin), the inclusion of meso-zeaxanthin may lead to the best results. Researchers also observed benefits with sustained supplementation with the macular carotenoids over a three-year period in patients with early AMD. Although many studies indicate positive results, for now, neither the NHS or HSE recommend prescription of these products, and a Cochrane review recommends that further trials are needed to promote the use of antioxidants and their role in the progression of AMD.9