A REVIEW OF THE CAUSES, SYMPTOMS AND TREATMENT FOR THIS DEBILITATING CONDITION

Although not life-threatening, migraine has been found to have a greater impact on quality of life than conditions such as heart disease and diabetes. The World Health Organisation classifies migraine as the 12th-leading cause of disability worldwide among women and the 19th overall.

WHAT IS MIGRAINE?

Migraine is more than just a headache. It is a complex, attacking neurological condition. With attacks lasting anything from a couple of hours to three days, it is easy to see why it can have such a debilitating effect on those living with the condition. Migraine affects 12-to-15 per cent of people worldwide (around 1 billion), with similar percentage figures reported (up to 500,000) for those living with the condition in Ireland. As many as 60 per cent of cases of the condition are inherited. Prior to puberty, boys experience migraine as often as girls. Once into adulthood, migraine becomes three times more common in women than in men.

This is due in large part to the hormonal changes in women from puberty to menopause. The highest prevalence is found in women around age 40, then tailing-off in the post-menopausal years. With such high numbers affected in Ireland, it stands to reason that there are also economic and work-related impacts to be considered. Approximately 92 per cent of Irish migraineurs report that attacks affect their performance at work, with 39 per cent of those sufferers being severely affected. Therefore, the unemployment rate for those with severe migraine is twoto- four times higher than the prevailing overall rate. Migraine accounts for the loss of over half a million working days in Ireland each year, with 37 per cent of working Irish migraineurs missing more than five days per annum — the resultant cost to the economy is at least €250 million.

CAUSES

Whilst the precise cause of migraine is unknown, it is accepted that it relates to the abnormal functioning of nerve cells that affect the brain’s ability to process information such as pain, light, sounds and other sensory stimulants. As the condition is very individual, how each migraineur arrives at this point is then determined by a varied number of ‘trigger factors’, but generally once there, a pattern emerges, and an attack ensues. These factors can be physical, environmental, or genetic and in most cases, it will be a particular individual combination that will precipitate an attack. Someone may experience all of the various stages of an attack, or only some of these during an episode. It follows, then, that identifying triggers is one of the keys to successful management of the condition.

SYMPTOMS AND TYPES

The word ‘migraine’ derives from the Greek word ‘hemikrani’ (half-skull), which means ‘pain on one side of the head’. This accurately describes and differentiates migraine from other types of headaches as typically, it presents on one side of the head. An attack may consist of some or all the following symptoms:

Migraine without aura (around 80 per cent of all attacks):

- Moderate-to-severe pain, throbbing one sided headache, aggravated by movement.

- Nausea and/or vomiting.

- Hypersensitivity to external stimuli (ie, noise, smells, light).

- Stiffness in neck and shoulders.

- Pale appearance.

Migraine with aura (in addition to above symptoms):

- Aura — around 20 per cent experiencevisual disturbances prior to the headache lasting up to one hour (most commonly blind spots, flashing light effect or zig-zag patterns; may also include physical sensations such as unilateral pins and needles in fingers, arm and then face).

- Blurred vision.

- Confusion.

- Slurred speech.

- Loss of co-ordination.

Difference Between Episodic Migraine And Chronic Migraine

Episodic migraine is defined as having 0-to- 14 headache days per month compared to chronic migraine, which is defined as having 15 or more headache days per month.

OTHER TYPES:

Basilar migraine

Usually affecting teenage girls, this is a rare form of migraine that presents additional symptoms such as loss of balance, fainting, difficulty speaking and double vision. There can be loss of consciousness during an attack.

Hemiplegic migraine(sporadic or familial)

Usually beginning in childhood, this severe form of migraine causes temporary unilateral paralysis. May also feature extended aura period that could last for weeks. Generally related to a strong family history of the condition. It is a rare form of migraine; diagnosis usually requires a full neurological exam, as the symptoms may be indicative of other underlying conditions.

Ophthalmoplegic migraine

In addition to headache, this very rare form of migraine shows additional symptoms, such as dilation of the pupils. Inability to move the eye in any direction, as well as drooping of the eyelid. It occurs primarily in young people and is caused by weakness in the muscles which move the eye.

Research indicates about 20 per cent of migraine attacks are brought on by dietary factors

Abdominal migraine

Symptoms are usually nausea- and stomachrelated rather than headache. Occurs predominantly in children, usually evolves into typical migraine with age.

TRIGGERS

A myriad of trigger factors, whilst in themselves not the cause of migraine, can build, bringing an individual to the point where a migraine attack is imminent. Again, these can be different for everyone and indeed, may differ for an individual each time, depending on their situation; trying to track down specifics can be difficult. Some of the most common triggers:

Environmental factors

Just moving around doing normal day-today stuff, which would not normally cost you a second thought, can be a potential danger for someone susceptible to migraine.

- Bright or flickering lights (could be cinema, shop displays or sunlight through trees whilst driving).

- Certain types of lighting (fluorescent, strobe).

- Strong smells (especially perfume, paint, etc).

- Weather (variety of factors, ie, bright sun glare, muggy close days, humidity).

- TV/computer screens and monitors.

- Loud and persistent noise.

- Travel areas of pressure change, ie, altitude.

Dietary triggers

Research indicates about 20 per cent of migraine attacks are brought on by dietary factors. Whilst people believe this to be the case, actual scientific evidence proving a link is virtually non-existent. In many cases, there may be other factors that precede consuming a ‘suspect’ food, which could contribute more to the onset of an attack, ie, lack of sleep, skipping meals. The most cited link is foods which are high in the amino acids tyramine and/or phenylethylamine, such as:

- Cheese (fermented, aged or hard mouldy types).

- Chocolate.

- Alcohol (beer and red wine particularly).

- Nitrites (common in processed meats).

- Sulphites (ie, preservatives in dried fruit and red and white wine).

- Additives (MSG).

- Aspartame (diet drinks).

- Caffeine (coffee, tea, etc; although caffeine can be used to prevent migraine, it is down to personal tolerance).

Hormonal triggers

Once females move into puberty and then adulthood, hormones play an increasing role in migraine prevalence. Oestrogen fluctuations due to menstruation or using oral contraceptive pills or HRT can sometimes trigger migraine. Conversely, migraine susceptibility can decrease during pregnancy, when oestrogen levels are high. In the main, migraine attacks lessen post-menopause (although can increase in the years preceding it). Identifying triggers can be the single most crucial step an individual can take in helping themselves to manage their condition. It may not be necessary to avoid situations completely, but instead build levels of awareness so that appropriate preventative steps and actions can be taken.

TREATMENT

The key to successful treatment is to establish correct diagnosis of migraine and eliminate other potential causes (tension or cluster headache in particular; see more at end of this article about non-migraine headaches). Some time spent with patients at an early stage reviewing their current medication regimen would prove hugely beneficial in identifying and/or preventing ‘medicine overuse headache’. In acute treatments, the goal is to stop or at least alleviate the effects of an attack once it has begun.

Analgesics

Used to target area-specific pain and especially if taken as early as possible once an attack begins, analgesics can be a hugely effective painkiller.

Aspirin

Traditional first line of defence, has anti-inflammatory properties that can help alleviate many of the physical symptoms of migraine.

Paracetamol

As effective as aspirin, but without the antiinflammatory effects.

Combinations

Drugs that contain aspirin or paracetamol along with another agent such as codeine or caffeine; codeine and other opiates are best avoided due to addiction, side-effect risk and risk over triggering ‘over-use headaches’.

NSAIDs

Generally used for more severe migraine attacks, evidence shows ibuprofen to be highly effective. Soluble forms may act quicker than tablet form for those where stomach issues are part of their migraine episode.

Triptans

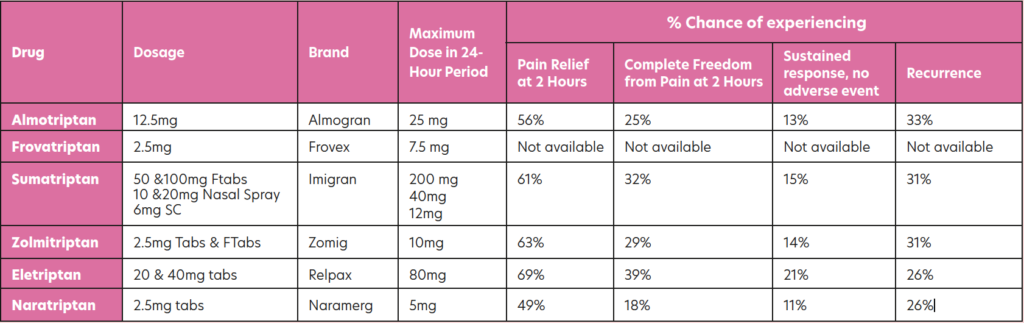

Triptans are highly effective, reducing the symptoms or aborting the attack within 30- to-90 minutes in 70-to-80 per cent of patients. Triptans target those neural serotonin receptors specifically involved in migraine attacks and can be used in the treatment of migraine with or without aura. All of them are available in tablet form, with some brands also available as fast-melt tabs, nasal spray, or SC injection. The table below shows those triptans available in Ireland, along with information from trials regarding effectiveness over the course of an episode. In all cases, these are only for treatment where migraine has been diagnosed and not for the treatment of hemiplegic, basilar or ophthalmoplegic migraine. Currently all are POM, apart from sumatriptan, which now has an option for sale OTC in the pharmacy for patients who have been prescribed it in the past.

PREVENTATIVE MEDICATION FOR MIGRAINE

Prophylactic medication may be considered if the patient has taken adequate lifestyle steps to prevent migraine, such as using a diary to determine triggers and avoidance of these triggers, but the migraine continues. It would be reasonable for a prescriber to consider prophylaxis for migraine if a patient must use analgesics for eight or more days of the month. Prophylactic medication should be tried for four-to-six months at a reasonable dose to determine if it is working effectively. Prophylactic medication has potential sideeffects that can limit dose or use. Amitriptyline, topiramate and flunarizine are the three most prescribed migraine prophylactic drugs, with amitriptyline being the most prescribed. Other prophylactics such as sodium valproate, pregabalin, gabapentin and pizotifen are considered second-line (often only used if the first three are not tolerated or ineffective).

Amitriptyline

A traditional tricyclic antidepressant but not used much for depression due to sideeffects, such as drowsiness, constipation, dry mouth, vivid dreams or nightmares and risks in people with glaucoma. It is dangerous in overdose. Low dose may be effective in preventing migraine; the dose for migraine varies between 10mg to 150mg, but the lower the better and it should only be titrated up slowly. Use at six months at maximum tolerated dose before considering changing.

Topiramate

Topiramate is traditionally an epilepsy drug that is sometimes used in low-dose form to prevent migraine. It must be used in caution in those with liver or kidney problems and must be avoided in pregnancy. Possible side-effects include nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhoea, decreased appetite, drowsiness and sleeping problems. Highest daily dose of 700mg but for migraine, recommended dose is 25mg to 200mg twice daily. Starting dose is 25mg at night for two-to-eight weeks and increase gradually.

Propranolol (Inderal)

This is an old-style beta blocker traditionally used for angina and blood pressure, but is rarely used for these indications nowadays due to safer, newer versions of beta blockers with less side-effects. However, in low doses, it is used for migraine prophylaxis in some. It should be used in caution in people with asthma, COPD, some heart problems, and diabetes. Side-effects can include cold hands and feet, pins and needles, tiredness and sleeping problems.

Flunarizine (Sibelium)

Flunarizine can take months to see a significant reduction in symptoms. Patients should be regularly reviewed to assess their response to this preventive treatment, and if a sustained attack-free period is established, interrupted flunarizine treatment should be considered.

Flunarizine maintenance treatment

If the patient is responding satisfactorily to flunarizine and a maintenance treatment is needed, the same daily dose should be used, but this time interrupted by two successive drug-free days every week, ie, Saturday and Sunday. Even if the preventative maintenance treatment is successful and well tolerated, it should be interrupted after six months and it should be re-initiated only if the patient relapses. Treatment is started at 10mg daily (at night) for adult patients aged 18-to-64 years and at 5mg daily (at night) for elderly patients aged 65 years and older. It is good practice to start at 5mg for all patients before titrating up. Side-effects include increased weight, increased appetite, depression, insomnia, constipation, stomach discomfort and nausea.

Gabapentin

Like topiramate, gabapentin is traditionally an epilepsy drug. It may be used if topiramate, flunarizine or propranolol are not effective or tolerated. However, in recent years, studies have indicated that gabapentin may not be as effective for preventing migraine as first thought. Side-effects can include dizziness, drowsiness, appetite increase, weight gain and suicidal thoughts. Sodium valproate is another epilepsy drug occasionally used for migraine prevention if other prevention options fail or are not tolerated. Other preventative medicines include Pizotifen (Sanomigran) and Pregabalin (Lyrica). Riboflavin (vitamin B2) There has been some indication that vitamin B2 supplementation may help prevent migraine; however, this has not been proven.

Botox

Botox injections were introduced in recent years as a preventive treatment for chronic migraine. It is administered in 30-to-40 injection sites located across seven head and neck muscle groups. It is administered every 12 weeks, as its effect wears off after this period. It should be administered by doctors specialising in administering Botox for migraine, as it is more complicated than simply administering Botox to points on the skin, as is done for its anti-wrinkle effect on the likes of the forehead. Patients need two bouts of Botox injections to be able to determine if it is working. While Botox use for migraine has varying degrees of success, it is shown to be successful (headaches cut in half) in 30-to-50 per cent of patients after two rounds of treatment, and this may increase to a 70 per cent success rate in patients after five rounds of Botox. Botox reduces migraine by reducing neurotransmitter signalling in the brain. The patient may still be prescribed other preventative drugs for migraine, even if getting Botox treatment.

NEW MIGRAINE DRUGS

A new class of migraine preventive drugs called anti-CGRPs are monoclonal antibodies that are synthetic proteins which bind to substances in the body/brain and have come to market in the last three years. These antibodies inhibit the action of a neurotransmitter called calcitonin gene-related peptide, or CGRP, by changing the peptide’s shape and attaching to its receptors in the brain. According to the European Headache Federation guideline on the use of monoclonal antibodies acting on the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) for migraine prevention, anti- CGRP medicines appear to be “promising drugs for migraine prevention”, but they state that “real-word data will be very important to support efficacy and safety of them, particularly in the long term. Future biomarker research should identify patients more prone to respond to anti-CGRP and enable clinicians to personalise treatment decisions.” The four CGRP inhibitors that have come to market in Europe and America are erenumab, fremanezumab, eptinezumab and galcanezumab. The two CGRP inhibitors that are currently licenced in Ireland are erenumab (Aimovig) and fremanezumab (Ajovy) and are subject to a strict protocol for prescribing that is still being developed by the HSE. Both eptinezumab and galcanezumab are currently not licenced in Ireland. Galcanezumab (Emgality) is undergoing assessment by the National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics (NCPE), which I discuss later, and at the time of writing (January 2022), the manufacturer of eptinezumab (Vyepti) has not looked for licencing in Ireland, so it is not yet subject to a NCPE review.

CGRP — ITS ROLE IN MIGRAINE

The neurotransmitter ‘calcitonin gene-related peptide’, or CGRP for short, plays a role in migraine. Its role in migraine includes: Being released in the trigeminal nerve. Increasing levels are seen during migraine attacks. It dilates blood vessels. It reduces mast cells (cells that control inflammation during allergic reactions). Causes an inflammatory fluid in blood vessels. For these reasons, CGRP inhibitors are effective in reducing migraine.

CGRP INHIBITOR AVAILABILITY IN IRELAND

As is the case when the EMA authorises any new medication in the EU, individual decisions about price and reimbursement take place at the level of each EU member state, so it does not automatically become the drug available immediately in each member state. In Ireland, it is the National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics (NCPE) that does a cost/ benefit analysis of any new drug a pharmaceutical company intends making available in Ireland, and then advises the HSE if it should become available for reimbursement on the HSE’s Primary Care Reimbursement Scheme. In early 2019, the NCPE first considered CGRP inhibitors for migraine and two of them were approved for reimbursement by the HSE by 2021.

ERENUMAB

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) authorised erenumab (Aimovig) in June 2018. It was the first monoclonal antibody to work by blocking the activity of calcitonin generelated peptide (CGRP) for use in the prevention of migraine. Erenumab is licensed for prevention of migraine in adults who have migraines a minimum of four days per month. The dose is a subcutaneous 70mg injection every four weeks. If not controlled with 70mg every four weeks, the dose may be increased to 140mg every four weeks, administered either as a single injection of 140mg or two injections of 70mg. Studies of erenumab scrutinised by the EMA to enable the authorisation decision shows that erenumab is effective at reducing the number of days migraines occur. A study of 667 patients with migraine on average 18 days per month had seven fewer days with migraines per month, compared with four fewer days for patients on placebo. A second study considered by the EMA studied 955 patients with migraines on average eight days per month; this study found an average of three-to-four fewer days of migraines per month with erenumab, compared with two fewer days for patients on placebo. The most common side-effects with erenumab (up to one-in-10 people) were reactions at the site of injection, constipation, muscle spasms, and itching. If the patient gets side-effects, they are normally mild.

NCPE: COST EFFECTIVENESS FINDINGS FOR ERENUMAB (AIMOVIG)

In January 2019, Novartis Ireland Ltd submitted a proposal to the NCPE detailing the comparative clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness of erenumab (Aimovig) for the prophylaxis of migraine in adults who have at least four migraine days per month. The NCPE cited clinical trial evidence showing that erenumab reduces monthly migraine days (MMDs) when compared to placebo. However, the NCPE was concerned about: Uncertainties around the dose required. ‘Responder threshold’ to be used in clinical practice, meaning they felt it was vague when erenumab should be prescribed. Whether the benefits of erenumab will be maintained when patients discontinue the therapy. The NCPE’s decision summary in September 2019 was that erenumab 70mg every four weeks is cost-effective to treat chronic migraine, but is not cost-effective at the dose of 140mg every four weeks to treat chronic migraine. Chronic migraine is defined as 15 or more headache days per month. The NCPE concluded erenumab, at either dose, is not cost-effective to treat episodic migraine. Episodic migraine is defined as 0-to-14 headache days per month. Concluding, the NCPE recommended erenumab for reimbursement at both the 70mg monthly dose and 140mg monthly dose for chronic headaches if what they described as the “cost-effectiveness for both doses can be achieved”. They recommended that erenumab only be prescribed for chronic migraine patients who have tried three or more prophylactic treatments unsuccessfully. The NCPE did not recommend the reimbursement of erenumab for episodic migraine due to cost-effectiveness concerns.

Chronic migraine is defined as 15 or more headache days per month

FREMANEZUMAB

On 7 September 2020, the NCPE completed its assessment and recommended that fremanezumab (Ajovy): Should be considered for reimbursement for the prophylaxis of migraine in adults with chronic migraine who have tried three or more prophylactic treatments unsuccessfully. Should not be considered for reimbursement for the prophylaxis of migraine in patients with episodic migraine who have tried three or more prophylactic treatments unsuccessfully, unless cost-effectiveness can be improved compared to existing treatments. This is the NCPE asking the manufacturer TEVA to bring down the price. Resulting from the NCPE guidance from September 2020, in March 2021, the HSE Drugs Group considered fremanezumab. Considering the NCPE guidelines and after “commercial negotiations” which took place in November 2020 (between TEVA and the HSE), the HSE’s Drugs Group recommended fremanezumab for reimbursement for its full licensed indications in October 2021. Following on, the HSE’s Managed Access Protocol (MMP) allowed access to eligible patients to the two CGRP inhibitors licenced in Ireland in October 2021 (more later). Compared to erenumab, fremanezumab offers the flexibility of either monthly dosing (225mg once monthly), or quarterly dosing (675mg every three months).

GALCANEZUMAB

Galcanezumab (Emgality) was the second monoclonal antibody the EMA authorised for the prevention of migraine in September 2018. It is still not available in Ireland. The National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics (NCPE) completed a rapid review of galcanezumab (Emgality) in January 2021; they deferred their approval decision until they receive more detailed analysis from its manufacturer Eli Lilly, known as a ‘Health Technology Assessment’ (HTA). The EMA authorisation for galcanezumab is for patients with a minimum of four migraine days per month. The benefits and safety data for galcanezumab that led to EMA authorisation came from three trials involving 1,780 patients with episodic migraine and 1,117 patients with chronic migraine. Patients with episodic migraine had a reduction of 1.9 monthly migraine days on average with galcanezumab when compared to placebo. Patients with chronic migraine had a reduction of two days of migraine per month while taking galcanezumab. The most common side-effects were pain and reactions at the injection site, vertigo, and constipation.

GALCANEZUMAB AND CLUSTER HEADACHES

On a separate very positive note for people living with cluster headaches, galcanezumab was granted FDA approval in 2019 in the US to treat episodic cluster headache. It was initially approved for migraine prevention by the FDA in 2018 and the FDA extended the licencing of galcanezumab to include treatment of episodic cluster headache after positive trial results. Studies showed that 71.4 per cent of patients had weekly cluster headache attacks cut in half with galcanezumab. It is the first new treatment to be approved for cluster headaches since triptans (and triptans were initially developed for migraine). While there is no licensing approval for galcanezumab in Europe and Ireland for cluster headaches yet, its success in American trials and subsequent FDA approval gives optimism that it will come to the market here to treat cluster headache in the coming years.

WHAT IS CLUSTER HEADACHE?

Affecting around 1 per cent of people, this is a rare but very severe headache found six times more commonly in men and usually begins in late 20s or early 30s. Typically, attacks begin in the middle of the night. Primary symptom is a severe stabbing pain affecting one side of the head. The side affected can vary between attacks but only in very rare cases would it affect both sides of the head at the same time. The duration of an attack can be between 15 minutes and up to three hours. Attacks come in clusters (hence the name) and can occur several times a day over a period of weeks or even months after each cluster, though attacks can disappear for months or years. A cluster attack can be distinguished from a migraine attack in that with cluster headache, the person is agitated during an attack or is unable to sit or lie at peace or find relief though sleep. During an attack, other symptoms may occur, such as red or watery eyes, runny nose, nasal congestion, or facial sweating. In addition, a sufferer’s eyes may be affected, with constriction of the pupil or drooping or swelling of the eyelid. Cluster headache is described by some medics as ‘the most painful event that can happen a person’, which emphasises the severity of the condition. Whilst the cause is unknown, suspected trigger factors include alcohol, tobacco, irregular sleeping patterns, and stress and decreased blood oxygen levels. The most common treatment for cluster headache is the inhalation of pure oxygen and is only successful if the mask fits perfectly without leaking.

HSE MANAGED ACCESS PROTOCOL FOR CGRP INHIBITORS

The HSE’s Managed Access Protocol (MMP) allowing access for eligible patients to the two CGRP inhibitors licenced in Ireland was approved and signed-off by Prof Michael Barry, Clinical Lead of the MMP, in October 2021. The HSE’s Medicines Management Programme has Managed Access Protocols in place for 11 classes of medicines (mainly new biological medication) as part of the reimbursement approval process. For the two CGRP inhibitors licenced in Ireland — Fremanezumab (Ajovy) from TEVA and Erenumab (Aimovig) from Novartis: HSE has the Hi-Tech Protocols for prescribing the treatments, meaning these medications may be prescribed only by consultant neurologists who have agreed to the terms of the HSE-Managed Access Protocol and have been approved by the HSE Medicines Management Programme for CGRP inhibitors.

GPs cannot prescribe them. Once pharmacists are presented with Hi-Tech prescriptions for erenumab (Aimovig) or fremanezumab (Ajovy) from approved consultants via the Hi-Tech hub, pharmacists can order these medicines via the Hi-Tech hub. Prophylactic treatments for which treatment failure with three drugs must be demonstrated prior to an application for reimbursement approval of CGRP inhibitors under the Hi-Tech Arrangement: The patient must have failed to get adequate treatment response from at least three of the following drugs: Amitriptyline/nortriptyline. Botulinum Toxin Type A (Botox). Candesartan. Flunarizine. Metoprolol/propranolol. Pizotifen. Sodium valproate. Topiramate venlafaxine. Not all these drugs are licensed for the prophylaxis of migraine; some are an offlicence use of these drugs.

BARRIERS TO PATIENTS ACCESSING NEUROLOGISTS

Migraine Ireland has flagged issues with the HSE’s Managed Access Protocol for CGRP inhibitors, including delays transferring patient records to the Hi-Tech scheme to allow access the two CGRP inhibitors currently approved in Ireland. A barrier to access for migraine patients is lack of access to neurologists in Ireland. Lack of neurologists in Ireland has long been a problem. As far back as 20 years ago, WHO commissioned an Atlas Country Profile Report (2001) on mental health resources and services, surveying 51 European countries. This report showed Ireland had the lowest number of neurologists per 100,000 population, at 0.38 neurologists per 100,000 in 2001. The report showed the average number of neurologists per 100,000 population out of 51 European countries was 5.82 per 100,000. Ireland was lower than former Eastern Bloc countries like Albania that were at the time only starting to recover from years of oppressive regimes and economic hardship. Even Bosnia and Herzegovina, which was not long out of a bitter civil war and still had 500,000 displaced refugees, had a higher number of neurologists per 100,000 than Ireland.

While the number of neurologists per 100,000 population in Ireland has increased slightly in the intervening 20 years, Ireland still has the lowest number of neurologists per 100,000 in Europe. According to the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland (RCPI) in a HSE-funded report in 2014, Ireland needs a minimum of 1.4 consultants per 100,000, which constitutes 64.3 consultant neurologists. Ireland currently has less than half this number of neurologists. It is difficult to find accurate figures on the number of neurologists in Ireland in 2022 but as of 2011, there were only 24 neurologists (only a few of these specialise in migraine) in Ireland, with a massive geographical imbalance; for example, at the time, there was only one neurologist north of the line from Dublin to Galway. All this means that the estimated 800,000 people in Ireland living with neurological conditions ranging from conditions like epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, brain tumours, spinal injuries, motor neurone disease, migraine, etc, must wait up to two years to see a neurologist. The Neurological Alliance of Ireland reported in March 2021 that more than 22,000 people were on a waiting list to see a neurologist, which was an increase of 40 per cent over five years.

These macro figures do not tell the whole picture. Even when patients eventually get to see a neurologist, Prof Orla Hardiman (professor of neurology at Trinity College Dublin and consultant neurologist at Beaumont Hospital) explained when interviewed by The Irish Times in March 2020 that follow-up diagnosis, treatment and care is a big problem. She explains how it is “difficult, in some parts of the country, to access diagnostic tests, for example public MRIs, so there will be waiting lists for imaging”. She explains a “barrier for patients is the scarcity of adequately staffed, dedicated neurology hubs” and that “we should have centres and hubs of neurology with four or five neurologists working together — or at least not less than three — but in parts of Ireland, that is not the case. We should have delivery of neurological care out of neurological hubs with diagnostic tests and experts, and good care in the community. We need to expand the number of neurology hubs in the country.” We have a “postcode lottery” when it comes to neurology care, with Prof Barry giving the example of “the sprawling region covered by counties Sligo, Mayo, Donegal, parts of Roscommon and Leitrim”, where “there are only two neurologists”. Prof Barry also lamented the lack of multidisciplinary teams to support neurologists by saying, “once a diagnosis has been made, there needs to be a good team in place, which has experts with a range of specialities, such as physiotherapists, speech and language therapists and psychologists”. While all this seems very depressing, lack of access to neurologists is familiar to GPs, pharmacists, and migraine patients alike and patient diagnosis and care are hampered by inadequate neurological resources in Ireland. While the HSE’s Managed Access Protocol allowing access for eligible migraine patients to CGRP inhibitors is very welcome, the biggest problem is getting timely access to the few neurologists in Ireland who specialise in migraine in Ireland and who can prescribe CGRP inhibitors under the Hi-Tech Scheme. There are currently five specialist clinics for headache and migraine based at Beaumont Hospital, Mater Misericordiae University Hospital, St Vincent’s University Hospital, Tallaght University Hospital (all four in Dublin), and Cork University Hospital, which provide access to new treatments like CGRP inhibitors. Private hospitals also offer access to neurologists specialising in migraine. On a more positive note, I spoke to two different Westmeath GPs who have two patients in their 30s under their care living with chronic migraine that massively impacted on their quality of life. Since they were both prescribed fremanezumab (Ajovy) in recent months, the impact of their level of migraine has been transformative, with the number of migraine days reduced by over 50 per cent for the two patients since they started the drug.

OTHER NEW MIGRAINE DRUGS ON THE HORIZON

Gepants

Gepants are a new class of drug that are relatives of anti-CGRP drugs like erenumab and fremanezumab; they also block the CGRP receptor and are effective at relieving migraine. They work quicker than anti-CGRP inhibitors like erenumab and fremanezumab. Rimegepant, ubrogepant and atogepant are examples of gepants. In America, rimegepant recently got FDA approval as both an acute and preventive treatment for migraine; ubrogepant got FDA approval as an acute treatment for migraine, while atogepant is being considered by the FDA as a preventive treatment for migraine. Gepants are oral medications. Side-effects include nausea, somnolence, and dry mouth. In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) is currently appraising rimegepant for treatment and prevention of migraine. Other gepants are also in the pipeline. They have yet to be considered by the EMA.

Ditans

Lasmiditan is a new oral medication and is the first of the ditan class. It is taken orally for acute attacks of migraine. It was recently approved by the FDA in the US and is not yet approved in Europe. It is not an anti-CGRP medication. It works by blocking the 5-HT 1F serotonin receptor, so is similar in its mechanism of action to triptans. However, triptans work by blocking the 5-HT 1B and 5-HT 1D receptors. Advantages of ditans over triptans is that there is decreased stimulation of the trigeminal system and unlike triptans, ditans do not cause vasoconstriction, so can be used instead of triptans when triptans are contraindicated due to cardiovascular issues.

THE PHARMACIST’S ROLE

Familiarise yourself with diagnostic criteria, which are available on www.migraine. ie to enable you to distinguish and recognise migraine and distinguish between migraine and other headache types, ie, cluster headaches, tension headaches. Enquire what treatments and medication the patient has used already to treat the headaches. Familiarise yourself with the stepwise analgesic ladder recommended for headaches and migraine, starting with paracetamol, aspirin, and ibuprofen. As sumatriptan is now classified as a P medicine (pharmacy-only), pharmacists should familiarise themselves with this and the protocol of when they can offer it to a patient, ie, patients 18-to-65 who have been previously diagnosed with migraine by their GP. Pharmacists should be able to identify when to refer to a GP. Familiarise yourself with the new CGRP inhibitors on the market and advise migraine patients who may be eligible on how to seek approval (via referral from their GP to an approved neurologist). ? References on request Disclaimer: Brands mentioned in this article are meant as examples only and not meant as preference to other brands.

CONTRIBUTOR INFORMATION

Written and researched by Eamonn Brady (MPSI), owner of Whelehans Pharmacies in Mullingar Tel 04493 34591 (Pearse St) or 04493 10266 (Clonmore). www. whelehans.inet. Eamonn specialises in the supply of medicines and training needs of nursing homes throughout Ireland. Email ebrady@whelehans.ie