The World Health Organization (WHO) defined osteoporosis in 2004 as a “progressive, systemic disease characterised by low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue, with a consequent increase in bone fragility and susceptibility to fracture”. The clinical measure of microarchitectural bone deterioration is based on a bone mineral density (BMD) T-Score of ?-2.5. T-scores represent numbers that compare the condition of the patient’s bones with those of an average young person with healthy bones. Fracture risk increases with decreasing BMD, with estimates indicating that for each standard deviation decrease in BMD, there is a twofold increase in fracture risk. In recent years however, BMD is now viewed as just one contributing risk factor to be considered in broader fracture risk assessment.

Fragility fractures cause severe pain, disability and reduced quality of life. Common sites for fragility fractures include the vertebrae, hip, distal radius, proximal humerus, and pelvis. Half of all women and 25 per cent of men over 50 will experience one or more fragility fractures. Fall related risk factors add to fracture risk significantly. In the UK, the cost of fragility fractures to the NHS is more than £4.7 billion per annum (549,000 fractures). About 52 per cent of people post hip fracture maintain their independence living in their own home after 120 days, and 26 per cent die within 12 months. Population ageing will increase the number of fragility fractures unless current practice is changed. Importantly, osteoporosis has no clinical manifestations until there is a fracture.

Additional risk factors

In addition to low BMD, the following factors contribute to fracture risk:

- Female sex;

- Increasing age;

- Low body mass index (BMI) is a significant risk factor for hip fracture;

- History of prior fractures (risk is approximately doubled in the presence of a prior fracture);

- Parental history of hip fracture;

- Smoking;

- Oral glucocorticoid therapy (increases fracture risk in a dose-dependent manner);

- Alcohol intake (three or more units daily are associated with a dose-dependent increase in fracture risk);

- Secondary causes of osteoporosis (eg, inflammatory bowel disease, endocrine disorders; but this risk increase may be confounded by coexisting factors like low BMD or use of glucocorticoids. By contrast, rheumatoid arthritis increases fracture risk independently);

- Diabetes (type 1 and type 2);

- Liability to falls.

- Other medications apart from steroids can increase hip fracture risk including thyroid hormone excess, aromatase inhibitors, and androgen deprivation for prostate cancer treatment. Medications such as antidepressants, antiparkinsonian drugs, antipsychotics, anxiolytics, benzodiazepines, sedatives, H2 antagonists and PPIs are also associated with increased risk. The mechanism behind many of these relationships and how they are mediated by other risk factors that may be present, such as low BMD or falls risk, is uncertain.

Diagnosis

A clinical diagnosis of osteoporosis may be made in the presence of a fragility fracture, particularly at the spine, hip, wrist, humerus, rib, and pelvis; or a T-score ?-2.5 standard deviations (SDs) at any site based upon BMD measurement by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA). It has also been suggested (by the National Bone Health Alliance, in the United States) that a clinical diagnosis of osteoporosis may be made if there is a clear elevated risk for fracture.

According to the National Osteoporosis Guidelines Group UK (NOGG) and the NICE guidelines, any postmenopausal woman or man over 50 with a clinical risk factor for fragility fracture should have a FRAX assessment to guide BMD measurement, and referral and prompt treatment if needed. The following clinical risk factors are included in FRAX assessment of fracture probability:

- Age;

- Sex;

- BMI;

- Previous fragility fracture, including morphometric vertebral fracture;

- Parental history of hip fracture;

- Current glucocorticoid treatment (any dose, by mouth for three months or more);

- Current smoking;

- Alcohol intake three or more units daily;

- Rheumatoid arthritis;

- Secondary causes of osteoporosis including type I diabetes, long-standing untreated hyperthyroidism, untreated hypogonadism/premature menopause, chronic malnutrition/malabsorption, chronic liver disease, non-dialysis chronic renal failure;

- Femoral neck BMD (optional).

The Irish Osteoporosis Society does not recommend the use of the FRAX tool because it includes a mere 12 risk factors, when in fact there are much more than this to consider (about 200 risk factors have been identified). Vertebral fractures, for example, are not included. The assessment also does not consider prior drug treatment for osteoporosis, or the magnitude of effect of several risk factors, ie, the presence of a history of two previous fractures carries a higher risk than one. Interpretation of the result requires clinical judgment. Currently, there is no standard policy for population based screening for osteoporosis and patients are identified through the presence of risk factors or due to a fragility fracture.

Vertebral fracture assessment is indicated in postmenopausal women or men over 50 if there is ?4 cm height loss, kyphosis (rounding of the upper back), long-term oral glucocorticoid use, a BMD T-score ?-2.5 at either the spine or hip, or acute onset back pain with risk factors for osteoporosis. Most vertebral fractures (about two thirds) are undiagnosed because medical attention is not sought.

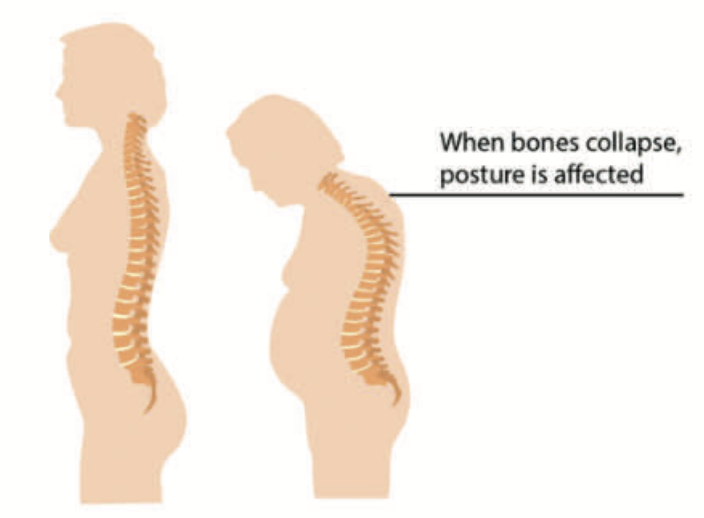

Osteoporosis and posture

If combined clinical risk factors (described above) are used to predict fracture risk, this performs similarly to using BMD alone as a predictor of fracture risk, however, use of both together is optimal. It is important to keep in mind that osteoporosis is commonly thought of as a woman’s disease. As a result of this, there is a potential for the diagnosis to be missed in men.

The following are signs and symptoms of possible undiagnosed osteoporosis in men and women:

- A fracture caused by a trip and fall from a standing position or less;

- Upper, middle, or low back pain, intermittent or constant back pain;

- Loss of height;

- Head protruding forward from the body;

- Shoulders becoming more rounded;

- A hump is developing (kyphosis);

- Changing body shape; a ‘pot belly’ developing.

- Non-pharmacological management of osteoporosis

The following is recommended for postmenopausal women, and men aged ?50 years with osteoporosis, or who are at risk of fragility fractures:

- A healthy, nutrient-rich balanced diet.

- An adequate intake of calcium (minimum 700mg daily) preferably achieved through dietary intake.

- Consumption of vitamin D from foods or vitamin D supplements of at least 800 IU/day. Dietary sources of calcium preferred. Supplementation should be targeted to those who do not obtain sufficient calcium from their diet and who are at risk of osteoporosis and/or fragility fracture, such as older adults who are housebound or living in residential or nursing care, and those with intestinal malabsorption, eg, due to chronic inflammatory bowel disease, or following bariatric surgery. Calcium and vitamin D supplements may increase the risk of kidney stones, but not the incidence of cardiovascular disease or cancer.

- A combination of regular weight-bearing and muscle strengthening exercise, tailored according to the individual patient’s needs and ability.

- Smoking cessation.

- Alcohol intake ? 2 units/day.

A falls assessment should be undertaken in all patients with osteoporosis and fragility fractures; those at risk should be offered exercise programmes to improve balance and/or that contain a combined exercise protocol.

There have been many randomised controlled trials of either calcium alone, vitamin D alone or both in combination, to examine whether use of these supplements alone reduces fracture risk. Meta analyses indicate that combined calcium and vitamin D supplements reduce hip and non-vertebral fractures, and possibly vertebral fractures.

Exercise has a beneficial effect on BMD, but there is actually no definitive evidence that it reduces fracture risks. Exercise effects differ depending on the skeletal site. Combination exercise programmes (weight bearing and resistance strengthening) reduce bone loss in the femoral neck and lumbar spine in postmenopausal women. The effect varies depending on intensity and duration. Repetitive forced spinal forward flexion exercises should be undertaken very cautiously or avoided in people with osteoporosis due to an increased risk of new vertebral fractures. In general however, the risk of serious adverse events is low for people with osteoporosis who exercise, and it reduces the risk of falls (and perhaps subsequent fractures) by maintaining muscle strength, balance and posture, improving confidence and reaction times. Postmenopausal women should engage in weight bearing exercise for at least 30 minutes on most days, and incorporate muscle-strengthening and posture exercises. Exercises that increase muscular strength and improve balance may provide the most benefit by decreasing risk of falls. For patients with frailty or history of vertebral fracture, brisk walking is sufficient and safe weight bearing exercise.

Risk of hip fractures reduces in those who stop smoking, compared with current smokers, only after five years.

Drug treatment should be considered in people with any history of fragility fracture: prior fragility fracture is a well-established risk factor for a future fracture.

Pharmacological treatment

Antiresorptive drugs primarily inhibit osteoclastic bone resorption with secondary effects on bone formation (ie, bisphosphonates, denosumab, HRT, and raloxifene). Anabolic drugs primarily stimulate osteoblastic bone formation with variable effects on bone resorption (ie, teriparatide). Most drugs fit into one or other category but romosozumab has a dual action, both stimulating bone formation and inhibiting bone resorption. Antiresorptive drugs are much less expensive.

It is important to consider the long-term management strategy for each patient initiated on osteoporosis treatment, as the timing of use of certain drugs is important. For example, teriparatide and romosozumab can only be used once in a lifetime, and denosumab requires careful consideration before initiation given the difficulties in stopping treatment once it is started. Most RCTs of osteoporosis drugs have included co-administration of calcium and vitamin D supplements. To replicate the positive outcomes noted in trials from these drugs, it is important for patients taking osteoporosis drug therapies to be vitamin D and calcium replete.

In most people at risk of a fragility fracture, antiresorptive therapy is the first line option. Oral bisphosphonates are most commonly offered. Alendronate is recommended for women with postmenopausal osteoporosis (PMO), men with osteoporosis, glucocorticoid induced osteoporosis (GIO), and the prevention of these. Risedronate is recommended for PMO, men with osteoporosis, GIO, and prevention of GIO in women. Ibandronate once monthly is recommended for the treatment of PMO.

Bisphosphonates should be taken after an overnight fast and at least 30 minutes (one hour for ibandronate) before the first food or drink (other than water) of the day or any other oral medicinal products or supplementation (including calcium). Tablets should be swallowed whole with a glass of plain water while the patient is sitting or standing in an upright position. Patients should not lie down for 30 minutes (one hour for ibandronate) after taking the tablet. Upper GI symptoms, bowel disturbance, headaches and musculoskeletal pain are some of the more common side effects from bisphosphonates.

Zoledronate infusion once annually is another option, recommended for the treatment of PMO, men with osteoporosis and men and postmenopausal women with GIO. IV zoledronate is included in first line recommendations after hip fracture.

Bisphosphonate treatment is associated with osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femoral fractures as rare but serious adverse effects. Defining the optimal duration of use helps to ensure the benefits outweigh these small risks. Bisphosphonates are retained in the bone long term, meaning that beneficial effects may persist for some time after treatment cessation. This has raised the possibility it may be beneficial to some patients to have a period of off treatment to restore the risk-benefit balance. Alternatives to bisphosphonates include denosumab, HRT, and raloxifene.

Calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3), the active form of vitamin D, is approved for the treatment of established PMO. It works mainly through inhibition of bone resorption. Calcium and creatinine levels should be monitored one, three and six months post-treatment initiation and six monthly thereafter to check for hypercalcaemia, hypercalciuria and kidney function. In postmenopausal women, calcitriol use is limited by potential adverse effects and a lack of consistent, demonstrated benefit. Patients on calcitriol should follow a low-calcium diet. Clinical trials of calcitriol in postmenopausal women have shown mixed results.

The initiation of HRT for treatment of osteoporosis should be limited to younger (<60) postmenopausal women with low baseline risk for adverse malignant and thromboembolic events

Denosumab is a monoclonal antibody against Receptor Activator of Nuclear factor Kappa B Ligand (RANKL) which regulates osteoclast development and activity. It is administered subcutaneously every six months, with safety and efficacy maintained over 10 years. Hypocalcaemia must be checked prior to use, and where due to vitamin D deficiency, treated with vitamin D. More common side effects include injection site reactions, hypocalcaemia, and flatulence. Cessation of denosumab leads to rapid BMD reduction and increased bone turnover, leading to an increased risk of vertebral fracture. This risk increase means that a plan for treatment continuation with an alternative antiresorptive drug is needed, ie a zoledronate infusion six months after cessation, or alendronate once weekly. Because of these issues stopping denosumab, careful consideration is required before starting it in younger individuals. Before starting denosumab, a long-term personalised osteoporosis management plan should be in place.

Some HRT formulations are approved for prevention of osteoporosis in PMO at risk of fragility fracture. Trials have shown that women using oestrogen-only therapy compared with placebo had significantly lower risk of fractures but significantly higher risk of gallbladder disease, stroke, venous thromboembolism and urinary incontinence. Women using oestrogen plus progestin in combination compared with placebo had significantly lower risk of fractures but had significantly higher risk of breast cancer, probable dementia, gallbladder disease, stroke, urinary incontinence and venous thromboembolism. Overall, the risk-benefit profile supports the use of HRT in management of osteoporosis in PMO <60 years old who have become menopausal within the last 10 years, and have menopausal symptoms and a low baseline risk for adverse events. The initiation of HRT for treatment of osteoporosis should be limited to younger (<60) postmenopausal women with low baseline risk for adverse malignant and thromboembolic events.

Raloxifene is a selective oestrogen receptor modulator that inhibits bone resorption. Side effects include leg cramps, oedema and vasomotor symptoms, with a small increase in the risk of VTE and stroke. Trials have indicated that raloxifene also reduces the risk of developing breast cancer.

Teriparatide (recombinant human parathyroid hormone) is an anabolic drug with most significant effects in trabecular bone. The treatment period is limited to 12 months. PTH needs to be checked prior to initiation to ensure pretreatment levels are normal. Side effects include headache, nausea, dizziness, postural hypotension and leg pain.

Romosozumab, a monoclonal antibody that binds to sclerostin, stimulates bone formation and inhibits bone resorption, and is approved for the treatment of women who are postmenopausal with severe osteoporosis who have experienced a major osteoporotic fracture (hip, vertebrae, distal radius, proximal humerus) within the previous 24 months, and who are at imminent risk of another fragility fracture.

Anabolic drug treatment (teriparatide or romosozumab) should be considered as first line treatment in postmenopausal women, and men, at very high fracture risk (particularly those with vertebral fractures); and as second line treatment if bisphosphonates are not suitable. After the approved duration of treatment (24 months with teriparatide; 12 months with romosozumab), a bisphosphonate (or raloxifene if appropriate) should be initiated without delay. The beneficial effects of teriparatide or romosozumab therapy were found to be maintained at the spine and hip, following treatment cessation, by both alendronate and denosumab.

The sequence in which treatments are used is important: the two available anabolic agents (teriparatide and romosozumab) which are licensed are for once-only treatment courses. Treatment with these results in rapid and greater fracture risk reductions than some antiresorptive treatments. This has led to the need to identify the subgroup of patients at very high fracture risk who would potentially benefit from a clinical review by an osteoporosis specialist, and who may benefit from anabolic drug treatment.

Because osteoporosis is a long-term condition, lifelong treatment and monitoring is required. Oral bisphosphonates can be prescribed for at least five years and then fracture risk reassessed. Longer durations of treatments are recommended in people who started the medication at the age of 70 or older

Few therapeutic studies have reported the recency of fracture in those patients whom they have recruited, though rapid clinical efficacy has been demonstrated within studies of zoledronate, risedronate, teriparatide and romosozumab.

Because osteoporosis is a long-term condition, life-long treatment and monitoring is required. Oral bisphosphonates can be prescribed for at least five years and then fracture risk reassessed. Longer durations of treatments (at least 10 years) are recommended in people who started the medication at the age of 70 or older, have a previous history of hip/vertebral fracture, those with ongoing use of oral glucocorticoids, or history of fragility fractures during the first five years of treatment. Monitoring the response to therapy is also important to identify patients who may require a change in therapy. Up to one-sixth of women taking alendronate continue to lose bone.

Special cohorts

Osteoporosis caused by androgen deprivation therapy in men (primarily used for the treatment of prostate cancer) is associated with rapid loss of BMD. Bisphosphonates and denosumab are effective drug treatments for preventing BMD reduction in these patients, although effects on fracture risk have not been demonstrated.

Bone loss and increased fracture risk occur early after initiation of oral glucocorticoids, and as a result, bone-protective treatment should be started in at-risk patients at the same time as glucocorticoid therapy. Bisphosphonates, denosumab and teriparatide are all treatment options.

All women starting aromatase inhibitor therapy should be assessed to identify if treatment to prevent osteoporosis is necessary as these medications induce bone loss.

The role of the pharmacist

According to the Irish Osteoporosis Society, pharmacists are in an ideal position to make the following interventions to improve outcomes in patient care:

Encourage anybody who has broken a bone from a trip and fall, or less, to have an assessment for fracture risk/development of osteoporosis.

Highlight to those who are on medications that cause bone loss that they are at an increased risk of fractures.

Check if any patients over 65 have had a DXA scan. Encourage anybody whose posture has changed (especially those who have developed kyphosis) to have a DXA scan with a lateral vertebral assessment (LVA).

Bibliography

- National Osteoporosis Guidelines Group UK. (2021). Clinical Guideline for the Prevention

and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Available https://www.nogg.org. uk/full-guideline - Irish Osteoporosis Society. (2020). Osteoporosis Fact Sheet. Available https://www. irishosteoporosis.ie/healthcare- professionals-2/general/

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. (2017). Osteoporosis: Assessing the Risk of Fragility Fracture [CG146]. Available https://www.nice.org. uk/guidance/cg146/resources/ osteoporosis-assessing-the- risk-of-fragility-fracture- pdf-35109574194373

- Rosen, H.N. (2022). Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and evaluation of osteoporosis

in postmenopausal women. UpToDate. Available https:// uptodate.com/contents/ clinical-manifestations- diagnosis-and-evaluation-of- osteoporosis-in-postmenopausal- women?search=strontium%20 and%20osteoporosis&topic Ref=2064&source=see_link