Discussing treatment of the various conditions with patients increases awareness of treatment expectations, potential adverse effects, recommended monitoring, and alternative options

Rheumatic disease encompasses a range of conditions that affect the joints, tendons, muscles, and ligaments. The most common of these are osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Fibromyalgia, gout, childhood/juvenile arthritis, lupus, and complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) are less common conditions that are also under the rheumatic disease umbrella.

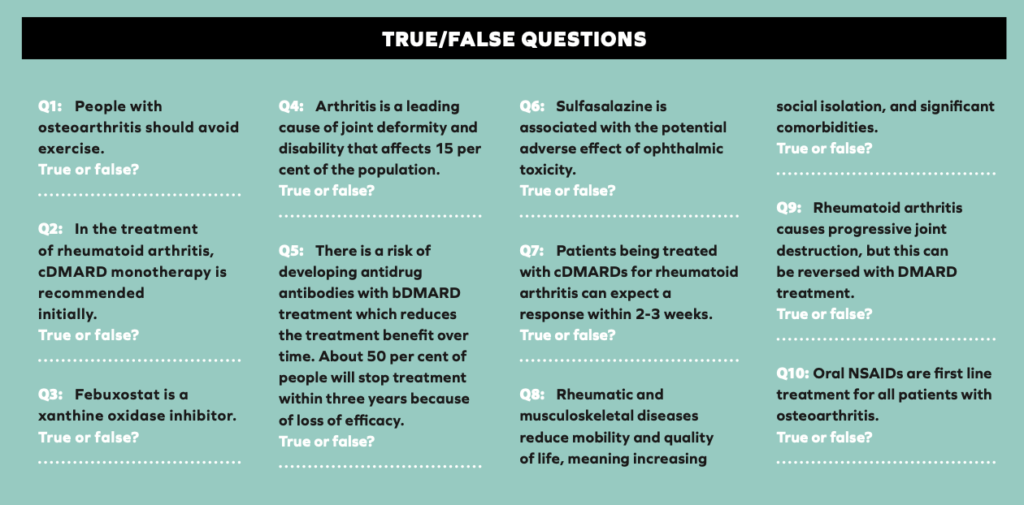

Rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases affect up to 60 per cent of the 120 million people in the EU, reducing mobility and quality of life, meaning increasing social isolation, and significant comorbidities, eg, atherosclerosis, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and obesity.3 Arthritis is a leading cause of joint deformity and disability that affects 15 per cent of the population here.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

RA is an inflammatory disease that often affects the small joints of the hands and feet, as well as the larger synovial joints.4 Because it is systemic, the heart, lungs, and eyes can also be affected. About 1.5 men and 3.6 women out of 10,000 develop RA each year, with peak incidence when people are in their 70s. About one-third of people with RA stop work within two years of disease onset. The aim of treatment is to relieve symptoms, particularly pain, and to slow or stop radiological progression, which is correlated with functional impairment.

Inflammation in RA is caused by autoreactive T cells, or locally by activated antigen presenting cells (APCs) that present autoantigen-derived peptides.5 In the affected joint, these T cells activate macrophages and fibroblasts through release of pro-inflammatory mediators (TNF-?, IL-17, IFN-?, and receptor activator of nuclear factor KB ligand; RANK-L). Activated macrophages also secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-?, IL-1?, and IL-6), establishing and maintaining this inflammation in the joint. Activated T cells also result in the production of anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs) and rheumatoid factor (RF) autoantibodies (antibodies to endogenous proteins), which can be used as markers for the disease. These autoantibodies further drive inflammation. Together with fibroblast-derived matrix metalloproteases, osteoclasts, and antibodies, activated neutrophils mediate inflammation-dependent cartilage destruction and bone erosion.

Persistent synovitis of unknown cause should be referred to a specialist. In early disease, treatment aims to suppress disease activity and induce remission, prevent loss of function, control joint damage, control pain, and enhance self-management. In established disease, management should address complications and associated comorbidity, as well as the effect of the condition on the person’s quality of life. Active RA is treated with the aim of achieving remission, or at least achieving low disease activity.4 There are multiple conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (cDMARDs) and biological DMARDs, with different mechanisms of action, to reach this target. The mechanisms of actions of pharmacological treatments are discussed in a later section. Throughout the treatment process, all risks, benefits, and additional information about the treatment and disease needs to be communicated to and discussed with the patient to help improve understanding of their condition.

In primary care, referral for a blood test for RF may be appropriate, and if this comes back negative, one for anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) test is also available;

An X-ray of the hands and feet in adults with suspected RA is also useful for diagnosis;

When diagnosis has been established, these blood tests and X-ray investigations should be performed if not done already, in addition to the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), which can be used to provide a baseline to assess response to treatment;

If anti-CCP antibodies are present or if the X-ray shows erosions, this can indicate an increased risk of radiological progression. Any flare-up of the disease means specialist care should be accessed again.

Measuring CRP can be useful to assess the level of disease activity in response to treatment.

In newly diagnosed RA:

cDMARD monotherapy is recommended initially, ie, oral methotrexate (MTX), leflunomide, or sulfasalazine. Subcutaneous MTX is an option for patients with side effects from oral treatment, and it may be superior due to increased bioavailability;

Hydroxychloroquine is an alternative in mild or palindromic arthritis (where symptoms flare and disappear);

Depending on how the drug is tolerated, dose can be escalated;

Glucocorticoids may be useful as a bridging therapy when starting cDMARDs. In some cases, these drugs may not elicit a full response for up to two to three months. The optimal dosing regimen for glucocorticoid bridging therapy, however, has not been established;

Where remission has not been achieved with one drug, additional cDMARDs can be offered in combination;

NSAIDs can be offered to help pain and stiffness when symptom control is inadequate (taking into account patient suitability factors). The lowest effective dose for the shortest time should be used, and a PPI should be offered;

Non-pharmacological management including from physiotherapists, occupational therapists, podiatry, psychological interventions, and certain dietary interventions (eg, the Mediterranean diet) are recommended in NICE guidance;

Six months after disease remission is achieved, a review appointment can be considered to ensure remission maintenance;

All adults with RA should at least have an annual review;

If the treatment target has been reached and maintained for a year without glucocorticoids, a cautious reduction in medication may be appropriate;

TNF-? inhibitors adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab, all with MTX, are recommended as options in RA if intensive therapy with two or more cDMARDs has not controlled the disease adequately, or if the disease is moderate.7 NICE considers abatacept (T-lymphocyte inhibitor) less cost effective than the other bDMARDs;

Because biological DMARDs are protein-based drugs, there is a risk of developing antidrug antibodies, which reduces the treatment benefit over time. About 50 per cent of people will stop treatment within three years because of loss of efficacy;

For severe disease, adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab (all TNF-? inhibitors), tocilizumab (IL-6 inhibitor), and abatacept, all in combination with MTX, are recommended as options for treating RA;6

In certain cases, adalimumab, etanercept, certolizumab pegol, or tocilizumab can be used as monotherapy for people who cannot take MTX;

Treatment with these bDMARDs should only be continued if there is a moderate response using European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) criteria at six months after starting therapy.

The management of patients who do not have a durable response to the initiated bDMARD can be challenging.8 Approaches include switching to a different agent in the same class, switching to a different class of bDMARD, or modifying concomitant DMARD treatment. However, the likelihood of response to subsequent bDMARDs decreases as the number of prior treatments increases.

Gout

Gout is caused by either increased production of, or reduced excretion of, uric acid. Following hyperuricaemia, urate crystals deposit in joints and tissues and activate the innate immune response. The symptoms of gout are rapid onset of severe pain with redness and swelling in joints (particularly the first metatarsophalangeal – big toe – joints), or tophi (large, visible bumps made of urate crystals). Serum urate levels can be measured to confirm the diagnosis (360micromol/litre or more). There is not enough evidence to promote any particular diet to reduce urate levels – a healthy, balanced diet is advised. People who are overweight, or drink alcohol excessively, are more likely to have flares.9

An NSAID (plus PPI), colchicine, or oral corticosteroid are first-line treatments for a flare, depending on the patient;

Intra-articular or intramuscular corticosteroid injections are options if NSAIDs and colchicine are not appropriate or ineffective;

Applying ice packs may help;

Urate lowering therapy (ULT) should be started at least two to four weeks after a flare has settled. In the past this was thought to exacerbate flares (when allopurinol 300mg was started); however, exacerbation is less common when starting with a low-dose ULT;

After an initial low dose of ULT, monthly serum urate levels should guide dose increases;

Allopurinol or febuxostat are first-line ULT options. Allopurinol can be offered as first line to people with significant cardiovascular disease.

Chronic Primary Pain

Chronic pain is often secondary to an underlying condition, but can also be primary.10 Fibromyalgia and CRPS are both examples of chronic primary pain (CPP). Fibromyalgia causes widespread physical pain, sleep problems, fatigue, and emotional and mental distress. CRPS is a broad term describing excessive and prolonged pain and inflammation that can occur following an injury or other medical event such as surgery, trauma, stroke, or heart attack.2 Chronic pain is estimated to affect between 13 and 36 per cent of the Irish population.11 The proportion of this which is CPP is unknown in Ireland, but in England the estimate of CPP is between one and six per cent. CPP seems disproportionate to any observable issues, and is only partially understood. All pain can be associated with distress and disability, but this is particularly true of CPP.10 The International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11, published in 2022) contains a relatively new definition for CPP.12 Unlike in the previous diagnostic manuals (DSM-5, ICD-10), a CPP diagnosis may be appropriate if there is no clear underlying cause of pain, unless another diagnosis would better explain the symptoms, ie, chronic secondary pain, where pain may at least initially be explained as a symptom due to an underlying disease.

Pain is always influenced by social and emotional factors, expectations and beliefs, mental health, and biological factors. In any pain assessment the impact of these should be considered. Clinical judgment and discussions with the patient can inform decisions about investigations for any injury or disease that may be the primary cause of the pain. Even if there is an initial diagnosis of CPP, this may change with time.10

Non-pharmacological management of CPP includes exercise, psychological therapy (ACT or CBT), and acupuncture;

An antidepressant (amitriptyline, citalopram, duloxetine, fluoxetine, paroxetine, or sertraline) can be considered for management of CPP in adults although this is an off-label use. Evidence indicates that these can help with quality of life, pain, sleep, and psychological distress in CPP, even without a diagnosis of depression. Most of this evidence comes from research findings from treatment of women with fibromyalgia;

Gabapentinoids, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, corticosteroid injections, ketamine, local anaesthetics, NSAIDs, opioids, or paracetamol should not be initiated in CPP due to lack of evidence of effectiveness;

In cases where patients are already taking these medications, a discussion with the patient is recommended to make a shared decision about whether to continue them or not.

This guidance on CPP by NICE is not without controversy. The Faculty of Pain Medicine of the Royal College of Anaesthetists published a document highlighting concerns over the NICE guidelines.11 The authors describe a real risk that those diagnosed with CPP based on the NICE guidance will include people with an ultimately identifiable cause of pain, to which this guidance should not apply. Significant concerns regarding the evidence base supporting the guidance are also raised.

Osteoporosis

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common form of arthritis, usually presenting as pain and stiffness in knee, hip, hand, and foot joints.14 It does not inevitably get worse with time, but symptoms may flare or fluctuate, and people’s physical, social, and emotional life can be affected. It is more common in women, older people, lower socioeconomic areas, and overweight and obese people. OA can be diagnosed in people over 45 who have activity-related joint pain, possibly with morning joint stiffness that lasts no more than 30 minutes. The core treatments are therapeutic exercise, and weight management (where appropriate), along with the provision of information and support.

Therapeutic exercise reduces symptoms and improves or maintains physical functioning over the long term. Although initial exercise may be difficult, it is not harmful to OA joints, and has general health benefits and a superior safety profile to pharmacological treatments;

Supervised exercise may be more beneficial in part due to the corresponding increase in social support, as well as enabling the exercise to be tailored;

In overweight individuals, losing 10 per cent or more of body weight may be the most beneficial, although any weight loss is beneficial. Advising on how much weight to lose to provide a target for people to work towards may be useful;

The evidence for the positive effects of weight loss for OA is mainly from knee OA, however, the reduction of inflammatory factors and increase in general wellbeing is likely to be beneficial for all OA patients;

Walking aids (sticks, crutches, walking frames) may help people with lower limb OA;

If pharmacological treatments are required, use them at the lowest effective dose for the shortest possible time;

A topical NSAID should be offered initially;

If ineffective or unsuitable, an oral NSAID can help, taking into account patient factors, with gastroprotection if appropriate;

There is no evidence that paracetamol reduces OA pain so it should not be used routinely.

LUPUS

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic systemic autoimmune disease with variable severity and flare-ups.15 In SLE, there are persistent immune responses against autologous nucleic acids. Damage to tissue from autoantibodies, or immune-complex depositions (made of antinuclear antibodies and nucleic acids), occurs in kidneys, heart, vessels, CNS, skin, lungs, muscles, and joints, leading to significant morbidity and increased mortality.16 It affects women more than men (about 10:1) and about 50 per cent of cases are mild at initial presentation. The disease tends to be more severe in patients of African or Latin American ancestry. UV radiation, smoking, and drugs (procainamide, hydralazine, infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept) can contribute to SLE, and there is a strong genetic component. SLE diagnosis is challenging in its early stages when symptoms may be vague, and a blood test for antinuclear antibody (ANA) may be negative. Up to 20 per cent of SLE patients may test negative for ANA at various stages of the disease course.15 Aims of treatment are either remission or low disease activity to prevent organ damage, and optimise health-related quality of life.

All lupus patients should receive hydroxychloroquine where appropriate;

In long-term maintenance treatment where glucocorticoids are being used, this should be only at doses of less than 7.5mg per day, and stopped when possible;

The use of immunomodulatory agents (methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate) can help with glucocorticoid discontinuation;

Belimumab, which inhibits B cell activation, can be considered for persistently active or flaring disease.

Mechanisms of Action Of Drugs to Treat Rheumatic Diseases

Conventional synthetic DMARDs

Glucocorticoids, eg, prednisolone, are highly potent anti-inflammatory drugs. They work by general suppression of gene expression.5 Glucocorticoids bind to intracellular glucocorticoid receptors, move to the cell nucleus, and reduce gene transcription of inflammatory molecules while promoting transcription of other genes that ultimately reduce inflammation.

The anti-inflammatory effect of hydroxychloroquine is likely through inhibition of lysosomal antigen degradation. This leads to reduced presentation of antigen: MHC II complexes to antigen presenting cells (APCs), preventing activation of T-cells and the following inflammatory responses. Hydroxychloroquine also inhibits the production of RF antibodies, and collagenase/proteinases which directly cause cartilage breakdown. Ophthalmic toxicity is the most important side effect (4.4-19 per cent). Even after cessation of therapy, retinal degradation can gradually progress.

Leflunomide interferes with cell cycle progression by inhibiting the mitochondrial enzyme involved in DNA and RNA synthesis (dihydroorotate dehydrogenase). This action inhibits the production of rapidly dividing cells, eg, autoimmune T-cells, and production of antibodies from B cells.16 It is also a tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Tyrosine kinases are involved in DNA repair, apoptosis, and cell proliferation. Lymphocytes (T-cells) cannot undergo cell division when the pathway for de novo synthesis of pyrimidines is blocked. Other cell types have the ability to use other pathways for pyrimidine synthesis, which may explain the relatively mild side effects of leflunomide. The dose-limiting side effects are liver damage, lung disease, and immunosuppression.2

The definitive mode of action of MTX is still not fully known, however, structurally it is an analogue of folic acid that interferes with dihydrofolate reductase.5 This inhibits nucleotide synthesis and purine metabolism. Through this, it produces adenosine, which has direct anti-inflammatory properties. The potential side-effects, including hair loss, stomatitis, nausea, and hepatotoxicity, are caused directly by the disruption of folate metabolism and can be prevented by folic acid supplementation.

Sulfasalazine is a prodrug of 5-ASA, and while the exact mechanism is unknown, it has been shown to have anti-inflammatory, immune modulatory, and antibiotic properties. Typical side-effects of sulfasalazine include fatigue, CNS reactions, nausea, abdominal pain (dyspepsia), diarrhoea, hypersensitivity reactions, and with a lower frequency of blood dyscrasias.

Targeted synthetic DMARDs

These drugs were developed specifically to disrupt the cytokine-mediated induction of inflammation, ie, the JAK-STAT pathway.5 When pro-inflammatory cytokines (eg, IL-6, IL-2, interferons, granulocyte colony stimulating factor) bind to their receptors on the outer surface of immune cells, Janus activated kinases (JAKs) are recruited to these receptors, inducing phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins (STATs). These then ultimately promote expression of many proinflammatory genes that initiate and sustain joint inflammation and damage. Tofacitinib was the first JAK inhibitor approved.

Biological DMARDs

There are four modes of action of current bDMARDs:5

Inhibition of TNF-? or the TNF receptor: infliximab, certolizumab, adalimumab, and golimumab are TNF-? neutralising antibodies. Certolizumab pegol is an anti-TNF-? antibody fragment. Etanercept is a soluble TNF receptor that binds TNF-?. Through inhibition of inflammatory processes caused by TNF-?, joint inflammation and bone/cartilage damage is reduced by these drugs. However, TNF-? neutralising antibodies have the potential to induce the production of anti-drug antibodies within about 18 months of treatment, which reduces serum drug levels, increases risk of hypersensitivity responses, and increases risk of thromboembolism. This issue is much reduced with certolizumab pegol.

Neutralisation of IL-6 directly or blockage of this receptor: Tocilizumab binds to the IL-6 receptor, blocking IL-6 induced proinflammatory binding. The most common side-effects of tocilizumab are skin and subcutaneous infections. However, infection rates are low and comparable to those observed upon treatment with anti-TNF-? antibodies:

Inhibition of T-cell co-stimulation by APCs: Abatacept is the first of these agents that suppress induction of inflammation upstream of the pro-inflammatory signalling cascade. It binds to APCs, blocking interaction between these and CD28, a protein on T-cells. The anti-inflammatory effects of abatacept were more pronounced in RA patients with higher levels of both ACPAs and RF autoantibodies. Abatacept is generally well tolerated by RA patients with the most frequent side-effects being upper respiratory tract infections, headaches, and nausea;

Depletion of B cells: Rituximab decreases B cells and diminishes the activation of T cells. Rituximab is overall well tolerated by RA patients, side-effects can include infections, infusion reactions, nervous system disorders, gastrointestinal disorders, and development of psoriasis.

Drugs that reduce uric acid

Colchicine has several effects: it prevents granulocyte migration into the inflamed joint; inhibits release of glycoprotein which aggravates inflammation; and binds to the intracellular protein tubulin causing disappearance of microtubules in granulocytes, which are essential for cell function. It also limits formation of IL-1? and IL-18.18

Xanthine oxidase enzyme is responsible for conversion of hypoxanthine and xanthine into urate, and by inhibiting this enzyme, allopurinol and febuxostat prevent formation of urate.

Conclusion

Pharmacists can enhance the management of rheumatic conditions through patient education. Interpreting current treatment guidelines and evidence based research as they apply to individual cases and prescriptions is important in order to determine the required patient education in each case. Discussing pharmacological (and non-pharmacological) treatment of these conditions with patients increases awareness of treatment expectations, potential adverse effects, recommended monitoring, and alternative options.

MCQs

Look at the following I. to IV. and answer questions 1 and 2 below.

I. TNF-? inhibition

II. JAK-STAT pathway inhibition

III. B cell inhibition

IV. IL-6 receptor inhibition

1. Which of the above describes the mechanism of action of tocilizumab?

2. Which of the above describes the mechanism of action of tofacitinib?

3. What is the mechanism of action of leflunomide?

I. Inhibition of DNA and RNA synthesis (via inhibition of mitochondrial dihydroorotate dehydrogenase)

II. Inhibition of lysosomal antigen degradation

III. Suppression of the transcription of inflammatory molecules

IV. It is an analogue of folic acid that interferes with dihydrofolate reductase

Look at the following a. to d. and answer questions 4 and 5 below.

a. Methotrexate

b. Gabapentinoids

c. Adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, tocilizumab and abatacept

d. Antidepressants

4. Which of the above (according to the NICE guidelines) is appropriate pharmacological treatment of chronic primary pain, eg, fibromyalgia?

5. Which of the above (according to the NICE guidelines) is usually the most appropriate first line treatment of rheumatoid arthritis?

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Rheumatic diseases and pain. Available at: www.cdc.gov/arthritis/communications/features/rheumatic-diseases-and-pain.html.

Breedveld FC, Dayer JM. (2000). Leflunomide: Mode of action in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, 59(11), 841-849.

St Vincent’s University Hospital Centre for Arthritis and Rheumatic Diseases. (2023). The research challenge. Available at: www.stvincents.ie/research-and-education/our-research-groups/centre-for-arthritis-and-rheumatic-diseases/.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2020). Rheumatoid arthritis in adults: Management [NG100]. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng100.

Lin YJ, Anzaghe M, Schülke S. (2020). Update on the pathomechanism, diagnosis, and treatment options for rheumatoid arthritis. Cells, 9(4), 880.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2019). Adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, tocilizumab, and abatacept for rheumatoid arthritis not previously treated with DMARDs or after conventional DMARDs only have failed. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta375.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2021). Adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab and abatacept for treating moderate rheumatoid arthritis after conventional DMARDs have failed [TA715]. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta715.

Strand V, Miller P, Williams SA, Saunders K, Grant S, Kremer J. (2017). Discontinuation of biologic therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: Analysis from the Corrona RA Registry. Rheumatology and Therapy, 4, 489-502.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. (2022). Gout: Diagnosis and management NG219. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng219/resources/gout-diagnosis-and-management-pdf-66143783599045.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2021). Chronic pain (primary and secondary) in over 16s: Assessment of all chronic pain and management of chronic primary pain [NG193]. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng193/resources/chronic-pain-primary-and-secondary-in-over-16s-assessment-of-all-chronic-pain-and-management-of-chronic-primary-pain-pdf-66142080468421.

Purcell A, Channappa K, Moore D, Harmon D. (2022). A national survey of publicly funded chronic pain management services in Ireland. Irish Journal of Medical Science (1971), 191(3), 1315-1323.

Nicholas M, Vlaeyen JW, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q , Benoliel R, et al. (2019). The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: Chronic primary pain. Pain, 160(1), 28-37.

Faculty of Pain Medicine of the Royal College of Anaesthetists. (2021). FPM Concerns regarding new NICE Chronic Pain Guidance. Available at: www.fpm.ac.uk/fpm-concerns-regarding-new-nice-chronic-pain-guidelines.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2022). Osteoarthritis in over 16s: Diagnosis and management [NG226]. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng226/resources/osteoarthritis-in-over-16s-diagnosis-and-management-pdf-66143839026373.

Fanouriakis A, Tziolos N, Bertsias G, Boumpas DT. (2021). Update on the diagnosis and management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 80(1), 14-25.

Pisetsky DS. (2019). The central role of nucleic acids in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. F1000Research, 8.

Drugbank Online. (2023). Leflunomide: Uses, interactions, mechanism of action. Available at: www.go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB01097.

Sahai R, Sharma PK, Misra A, Dutta S. (2019). Pharmacology of the therapeutic approaches of gout. In Recent Advances in Gout. London, UK: IntechOpen. Available at: www.intechopen.com/chapters/66515