The Remarkable Transformation Of HIV Therapies Has Provided The Opportunity To Manage It As A Chronic Disease.

INTRODUCTION

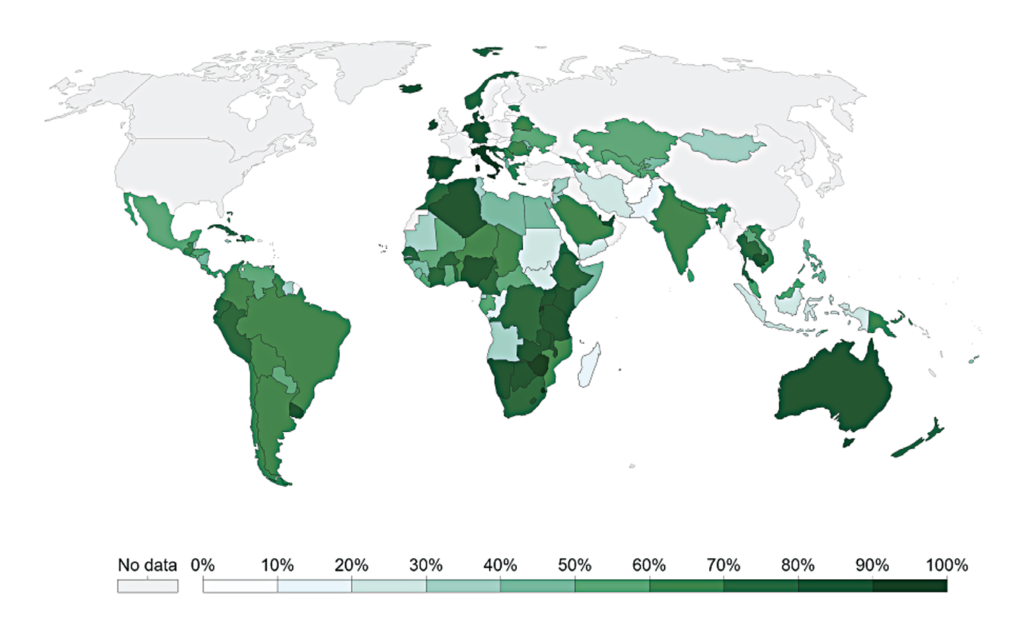

It is estimated that currently, about 40 million people are living with HIV worldwide.1 HIV has caused more than 30 million deaths since the early 1980s — nearly one million people annually on average.2 Worldwide in the 1990s, there was a surge in the infection rate: Between 1996 and 2001, more than three million people were infected each year. This rate started to slow after this period, and has reduced to below two million annual infections since 2017. In some countries, however, particularly those across Sub-Saharan Africa, at the moment it is still the leading cause of death. Across most regions of Europe, it accounted for less than 0.1 per cent of deaths in 2019, whereas in, ie, South Africa, 28 per cent of deaths were attributable to HIV/AIDS in the same year.

ANTIRETROVIRAL THERAPY

The availability of life-long antiretroviral therapy (ART) has transformed the disease from being severely debilitating and likely fatal, to a manageable chronic health condition.1 Globally, 1.2 million deaths were avoided in 2016 as a result of ART. Without ART, it is estimated that twice as many people would have died from HIV/AIDS. Very few people with HIV live beyond 10 years after diagnosis without ART; however, people today in high-income countries who start it in their 20s can expect to live well into their 60s. This is still not the equivalent life expectancy as that of the general population, but is improving due to the development of newer ART, fewer side-effects, better education and compliance, and better support.2

Figure 1 shows the percentage of people in the world with HIV diagnoses receiving ART, broken down by country, where data is available. The population of people receiving ART globally has increased significantly: In 2005, only two million people in the world were taking ART. By 2018, this had increased substantially to 23 million. However, 23 million is still just a proportion — 61 per cent — of all people with HIV. To increase treatment coverage, access to testing needs to be improved.

Studies suggest that acute HIV infection may have a huge role in the spread of the disease, with predictions estimating that it is responsible for between 10 and 50 per cent of new cases.3

People with HIV who do not have detectable plasma loads cannot transmit the virus to others; however, the diagnosis needs to be made and treatment needs to be commenced in order to make this a reality.1 The lack of insight or awareness into many cases of positive HIV status presents a substantial barrier to the aim of achieving no further spread of infection or deaths.3 Among people with HIV who do know their status, stigmatisation both from others (usually coming from fear about HIV), and internalised stigma, leads to a decrease in engagement with care, treatment and prevention services.2

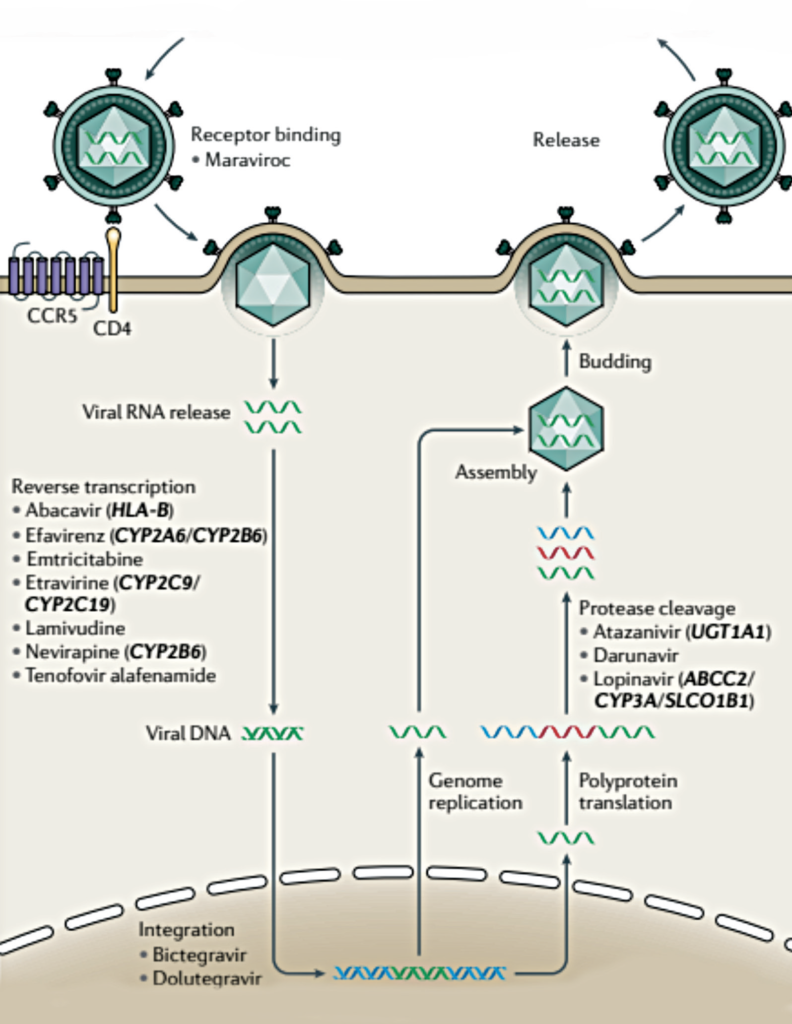

Multiple mechanisms along the route of HIV infection of host cells have been targeted for drug treatment

In 2014, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS) set targets: 90 per cent of people with HIV will know their status, 90 per cent diagnosed will be on ART, and 90 per cent on ART will be virally suppressed. They aimed to achieve this by 2020.3 By the end of 2017, 75 per cent knew their status, and there were still nearly two million new HIV infections.

HIV INFECTION

The compromised immune system in HIV is due to a loss of CD4 T cells,4 which is the target cell of the HIV virus.1 HIV enters the cell after binding to the CD4 receptor (via HIV envelope protein gp120), and to a co-receptor, CC-chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5). This leads to a fusion of the virus with the CD4 cell, permitting the eventual production of new virus particles. HIV uses the host cell synthesis machinery to replicate, and also integrates a copy of its own RNA genome into the infected host cell chromosome, making it a very persistent and challenging virus to eradicate fully. Health complications and mortality rate increase as the amount of these CD4 T cells decline.

Before publication in 2015 of the START study,4 which followed 4,685 patients with HIV in 35 countries for an average of three years, it was common practice to delay the initiation of ART in asymptomatic patients until their CD4 cell count dropped below a certain threshold, whereas now, ART is started as soon as possible. The immediate initiation of ART was found by the START study to be more effective, with a 72 per cent relative reduction in serious AIDS-related events in the immediate-initiation group.

ANTIRETROVIRAL THERAPY MECHANISMS

Multiple mechanisms along the route of HIV infection of host cells have been targeted for drug treatment. The following drug classes1 have been developed (see Figure 2):

- Entry inhibitors (which prevent viral binding of the viral gp120 protein to the host cell receptor, and viral binding of the virus to the CCR5 receptor).

- Nucleoside and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (preventing transcription of viral RNA into DNA).

- Integrase inhibitors (preventing integration of the viral genome into the host’s genome).

- Protease inhibitors (preventing cleavage of viral polyproteins into functional units).

Severe adverse events have been observed for several classes of these drugs, some of which have been attributed to population genetic variation. It is important that the ART is tailored to the individual, and in some situations, the population also.

Clinical and epidemiological studies have noted that differences in the course of HIV infection are not completely explained by variables such as age and comorbidities. One of the now most-recognised contributors to resistance against HIV infection is related to the CCR5 receptor: People who carry two loss-of-function variants in the gene encoding are resistant to HIV infection. This was first identified in a group of men who have sex with men (MSM) who, despite multiple exposures to the virus, did not become infected. These people all carried a deletion in the CCR5 gene (the CCR5?32 allele) that produced a non-functional CCR5 receptor.

Interestingly, it is bone marrow transplants between CCR5?32 donors and recipients with HIV infection that have resulted in the only three confirmed cases of long-term HIV cure. This genetic variant is seen in about 10 per cent of Europeans, and is not observed in any significant frequency in other continental populations. However, as in many diseases, high-income populations have been disproportionately studied: As genetic studies expand to include more diverse populations, additional discoveries in the genome may be expected.

One of the now most-recognised contributors to resistance against HIV infection is related to the CCR5 receptor

HIV IN IRELAND

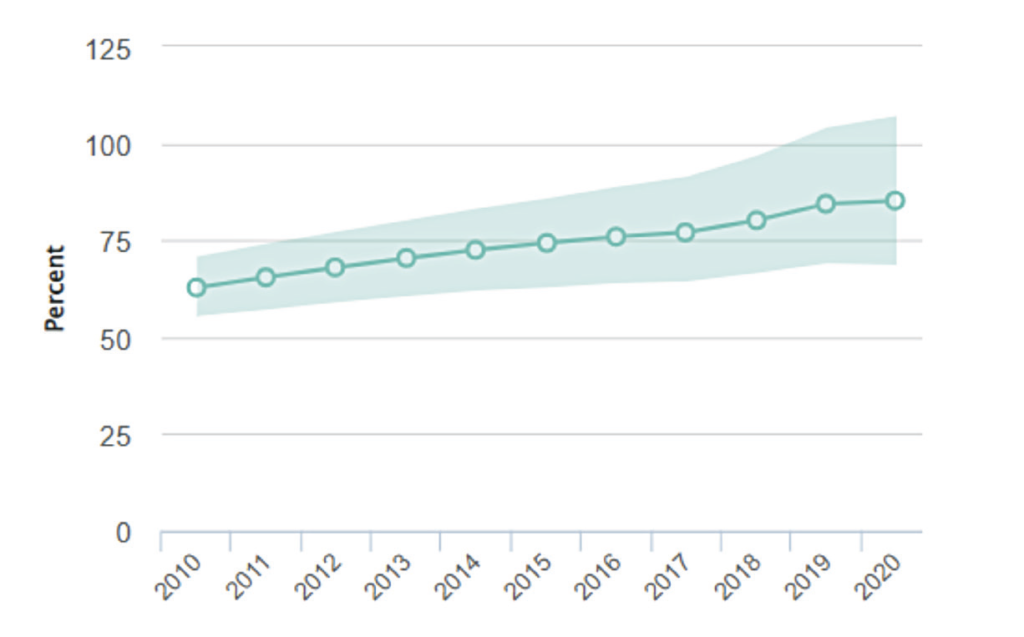

An estimated that 7,800 people are living with HIV in Ireland.5 About 15 per cent of people infected here with HIV are unaware of their infection status.6 Figure 3 shows the percentage of people in Ireland receiving ART since 2010.5 In the years 2003 to 2015, about 300-to-400 people were testing positive each year.6 Since 2015, this seems to be increasing, to 400-to-500 cases annually. About 50 per cent of cases of HIV in Ireland are among MSM, with the other 50 per cent among heterosexual men and women, and intravenous drug users.

Voluntary community-based HIV testing (VCBT) services are offered for free in a variety of non-clinical community settings, including mobile and outreach, for example NGOs, including, ie, AIDSWest, GOSHH, the Sexual Health Centre (SHC) Cork; and via the KnowNow programme in Galway, Limerick, Cork and Dublin.7 These services target people most at risk of HIV infection, with the aim of improving detection and therefore early treatment initiation, and decreasing onward transmission.

VCBT is performed using either standard methods, which involves sending a blood sample to a lab for testing, or rapid point-of-care testing (POCT), where a rapid diagnostic test is used, and if indicative of a positive result, the person is sent to a confirmatory testing service. The Health Protection Surveillance Centre started monitoring VCBT (collating anonymised data from January 2017 onwards) to identify any trends in infection rates and to determine if target groups are being effectively reached in the community. The most recent report from 20208 recorded 5,607 VCBTs in 2019, 92 of which were indicative of a HIV-positive result (1.6 per cent). The rate was higher in females (2.2 per cent) than males (0.5 per cent), and in terms of demographic breakdown, the highest rate was observed in migrants from countries with high HIV prevalence, and second-highest in MSM. The median age among those with positive/reactive tests was 34.

For people who may have been exposed to HIV infection risk, post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is available in Ireland: It is a course of medication that can be started for up to 72 hours after HIV exposure, which reduces the chance of HIV infection.6

It is available for free from genitourinary medicine/STI clinics and emergency departments (although there may be a charge for using the emergency services).

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) medication is taken before exposure to HIV to prevent infection. It has been made available in Ireland through the HSE in recent years, and can also be obtained through a GP or STI clinic. Detailed guidelines on the use of PrEP are available from the British HIV Association/ British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. Baseline HIV testing prior to starting PrEP is crucial, since initiation in the context of undiagnosed HIV infection could lead to development of antiretroviral resistance.9

Donna Cosgrove graduated with a BSc in Pharmacy from the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland. She then returned to university to complete a MSc in Neuropharmacology, which led to a PhD and further research investigating the genetics of schizophrenia. Over the years Donna has worked in hospital, research and community pharmacy settings, but currently works as a community pharmacist in Galway and as a clinical writer.

References

1. McLaren PJ, & Fellay J (2021). HIV-1 and human genetic variation. Nature Reviews Genetics, 22(10), 645-657.

2. UNAIDS (2022). What can be done to prevent HIV/AIDS? World Development Indicators – World Bank. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Available https://ourworldindata.org/hiv-aids [Online Resource].

3. Elliott T, Sanders EJ, Doherty M, Ndung’u T, Cohen M, Patel P, … & Fidler S (2019). Challenges of HIV diagnosis and management in the context of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), post?exposure prophylaxis (PEP), test and start and acute HIV infection: A scoping review. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 22(12), e25419.

4. Insight Start Study Group (2015). Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. New England Journal of Medicine, 373(9), 795-807.

5. https://www.unaids.org/en/ regionscountries/countries/ireland.

6. Health Service Executive (2017). A Guide to HIV. Available https://www. sexualwellbeing.ie/sexual-health/ sexually-transmitted-infections/ information-on-hiv/hiv.pdf.

7. Health Protection Surveillance Centre (2019). Monitoring Community HIV Testing in Ireland 2018. Available https://www.hpsc. ie/a-z/hivandaids/hivtesting/ Monitoring%20Community%20 HIV%20Testing%20in%20 Ireland%202018_Final.pdf.

8. Health Protection Surveillance Centre. Monitoring Community HIV Testing in Ireland, 2019 (2020). Available https://www.hpsc. ie/a-z/hivandaids/hivtesting/ Monitoring%20Community%20 HIV%20Testing%20in%20 Ireland%202019_Final.pdf.

9. British HIV Association/British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (2018). BHIVA/BASHH guidelines on the use of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Available https://www.bhiva.org/ file/5b729cd592060/2018-PrEP-Guidelines.pdf.