A synopsis of the treatment and management options in overactive bladder (OAB), including the role of medications and self-help options.

OAB is an issue for many people, sometimes regardless of their age. However, the condition affects approximately 350,000 of people over the age of 40 years in Ireland. In terms of quality of life, up to 67 per cent of women with OAB report that it has a negative effect on their daily lives. In many cases, the exact cause of OAB is unknown, but it is known that stress can worsen the condition and the types of fluid a patient drinks can also have an effect on their symptoms.

The International Continence Society (ICS) defines OAB as symptoms of urgency with or without urge incontinence, usually associated with urinary frequency and nocturia in the absence of local pathology and significant endocrine factors. OAB can also be associated with detrusor overactivity on urodynamic testing.

The prevalence of OAB is reported at 12-to-17 per cent of the population, and this figure significantly increases with age. OAB has a greater impact on life than stress urinary incontinence and is responsible for several other comorbidities, including falls and fractures, depression, and increased risk of admission to hospitals and nursing homes.

DIAGNOSIS

OAB is a diagnosis of exclusion. An examination needs to be conducted on all patients and should include assessment of urinary, gynaecological and neurological systems. Abdominal palpation and vaginal examination will enable identification of a palpable bladder, prolapse or pelvic mass, as well as helping to determine the patient’s oestrogen status.

In men, OAB symptoms frequently go untreated for a number of reasons. Symptoms of OAB in men are often attributed to bladder outflow obstruction (BOO) in males, resulting in misdiagnosis and delays in treatment. The European Association of Urology (EAU) recommends focused abdominal, genital, rectal, and neurological investigations. In particular, says the EAU, a digital rectal exam is imperative to rule out the presence of prostatic hypertrophy, malignancy, and poor rectal tone. There can be certain high-risk neurological causes of OAB, such as spinal cord injury, myelodysplasia, or multiple sclerosis. Outruling these is key, as these patients may be at risk of upper tract deterioration/renal failure.

Another important tool is a voiding diary spanning 48-to-72-hours. This gives a more comprehensive picture of the pattern of voiding than can be obtained from just the patient’s history. Information obtained should include the number of fluids consumed (types and volume); voids during daytime, night-time, and over a 24- hour period; volume of urine over 24 hours; maximum voided volume; average voided volume; median maximum voided volume; and nocturnal volume.

A urinalysis should be done to exclude a urinary tract infection, and glycosuria, which might indicate the presence of diabetes.

Secondary investigations include urodynamic testing, a cystoscopy, and imaging of the upper urinary tract. Secondary investigations should be considered in patients with — for example — neurological disease, refractory OAB, or those in whom initial investigations raise the suspicion of an underlying problem that may require further investigation or treatment.

Another important tool is a voiding diary spanning 48-to-72-hours

www.oab.ie, an Irish resource for OAB sufferers, provides a list of suggested questions a person newly-diagnosed with the condition can ask their GP or specialist physician. It may be possible for the patient’s pharmacist to address some of them. The questions include:

- Are there medications that I can take to treat my OAB?

- If these medicines have any side-effects, what can I do to help manage them?

- If the medication works and my OAB improves, can I stop taking the medicine?

- Are there risks in not treating OAB?

- Are there any complications associated with overactive bladder?

- Will OAB keep me from having a normal sex life?

- Are there support groups for people with bladder problems in Ireland?

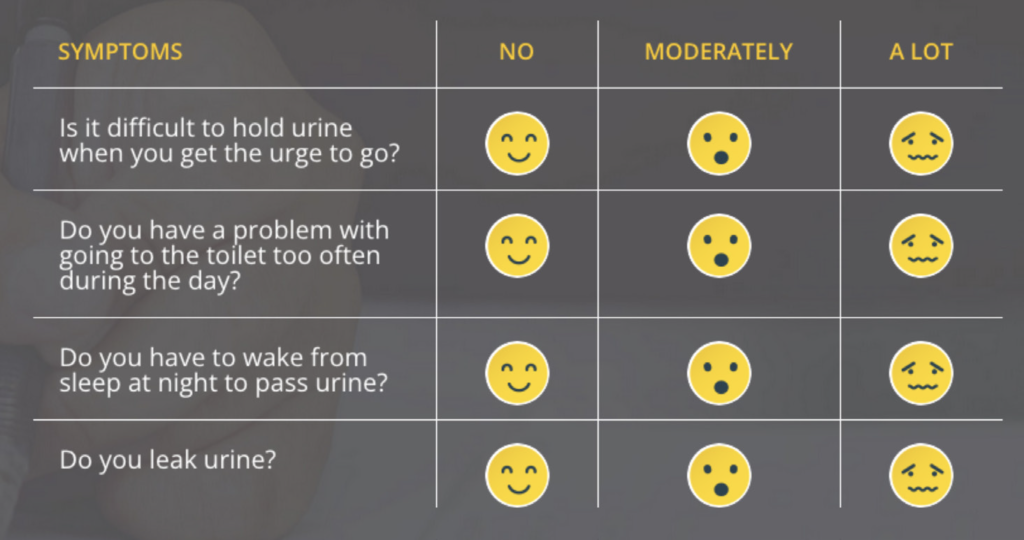

This list is not exhaustive and oab. ie also provides a resource for people to self-assess in order to possibly determine whether they suffer with the condition. Whilst this is not intended to replace the advice of a medical professional, the basic elements of the self-assessment are displayed in Figure 1.

HISTORY

When eliciting the patient’s history, a wide differential must be considered, which may be contributing to the symptoms. A number of points should be elucidated from the patient’s history via targeted questions. These include:

- Do you ever have leaking/wetting during the day/night?

- Does the need to urinate wake you?

- How often do you urinate during the day?

- Do you ever have the sudden urge to urinate and feel you can barely make it to the bathroom?

- How often do you get up to go to the bathroom after going to sleep?

- Do you ever leak urine during sex?

Urodynamic testing is also useful in the assessment process. It aims to evaluate incontinence objectively and also to differentiate between different types of incontinence, so that the most effective method of treatment can be selected.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

LIFESTYLE CHANGES

An important part in the management of OAB includes the patient being willing to make some lifestyle changes. These include adjusting volume, timing, and types of fluids — this involves maintaining an adequate intake of six-to-eight cups (1,500-2,000ml) of fluids per day. It also includes decreasing evening fluid intake — particularly if the patient complains of nocturia — and decreasing intake of caffeine and other fluids that can cause irritation to the bladder, such as spicy food, citrus, tomato, alcohol, and carbonated drinks. Some drinks that are not an irritant to the bladder include water, fruit teas, caffeine-free tea, coffee and milk.

If they are overweight, it is also important to ask the patient to lose weight, as weight loss has a significant positive effect on leakage. They should also be advised to quit smoking, and increasing dietary fibre will help them to avoid constipation.

BLADDER TRAINING

The purpose of bladder training is to increase the voiding interval and decrease urgency and associated urge incontinence. Also called ‘bladder drill’, bladder training works by activating cortical inhibition over the sacral micturition ref lex centre. There are usually three components to this training: Patient education; scheduled voiding; and positive reinforcement.

The process should be undertaken in small stages. For example, if the patient is going to the toilet every 30 minutes, they should try extending the time (or ‘holding it in’) by 10 minutes for one week, then by 15 minutes for another week, and then 30 minutes, and so on. Ideally, eventually they should be able to hold on for three-to-four hours between urination.

SUPPRESSING URGENCY

There are different techniques for this, and ‘one size does not fit all’. Techniques include sitting straight on a hard seat, distracting oneself by reading, doing puzzles, for example, and contracting the pelvic f loor muscles. These approaches may help gradually, but patience is required, as it may take weeks or months of perseverance before noticing any significant improvement.

PELVIC FLOOR EXERCISES

Another key part of the management is behavioural therapy, which includes pelvic f loor muscle training, urge suppression, and bladder retraining. Pelvic f loor rehabilitation programmes are aimed at strengthening the pelvic f loor musculature. These exercises should be done in conjunction with lifestyle modifications.

Rehabilitation programmes may include exercises performed with biofeedback, pelvic muscle contractions stimulated by functional electrical stimulation (FES), motor-relearning exercises, simple oral or written information, or any combination of these. Success is dependent on a continuous, regular home exercise programme to avoid deconditioning.

PHARMACOLOGICAL THERAPY

In primary care, patients presenting with typical overactive bladder symptoms can be treated empirically with an anticholinergic agent and they may gain clinical benefit without the need for invasive urodynamic procedures. The anticholinergic medication options are illustrated in Table 1.

A relatively new drug used is Mirabegron, which is a ?3-adrenoceptor agonist with a mechanism of action that is distinct from anticholinergics. Therefore, it has fewer side-effects and is considered as a second-line therapy when patients are intolerant to anticholinergics.

The choice of anticholinergic therapy should be guided by individual patient comorbidities, as objective efficacy of anticholinergic drugs is similar. Dose escalation does not improve objective parameters and can cause more anticholinergic adverse effects. It is, however, associated with improved subjective outcomes. To decrease side-effects, switching to a lower dose or using an extended-release formulation or a transdermal delivery mechanism should be considered.

Absolute contraindications to anticholinergic use include urinary retention, gastric retention, uncontrolled narrow-angle glaucoma, and known hypersensitivity to the individual drugs or their ingredients.

Relative contraindications that warrant cautious use include partial bladder outlet obstruction (borderline or high post-void residuals); decreased gastrointestinal motility; constipation; impaired cognitive function; reduced renal or hepatic function; controlled narrow-angle glaucoma; concomitant excessive alcohol use (added sedating effects); and myasthenia gravis.

The choice of anticholinergic therapy should be guided by individual patient comorbidities

Elderly patients in particular should be monitored for drug interactions or polypharmacy of drugs with anticholinergic effect (ie, antidepressants, antipsychotics, anxiolytics), as the overall anticholinergic load is associated with confusion, falls, and fractures.

Anticholinergics are classified as category C drugs in pregnancy, and should be used only if the benefits clearly outweigh the risk.

REFERRAL TO SECONDARY CARE

A GP must identify certain ‘red f lags’ that warrant referral to a specialist urogynaecologist. These include:

- Failed medical treatment.

- Significant vaginal prolapse.

- Bladder pain.

- Recurrent urinary tract infections.

- Haematuria.

- Voiding difficulty, or chronic urinary retention.

WHEN MEDICATIONS ARE INEFFECTIVE

In the event that medications are not effective, one of the options includes intravesical Botox injections. Intravesical botulinum toxin A prevents acetylcholine release at the neuromuscular junction, resulting in temporary chemodenervation and muscle relaxation for up to six months. The technique is to place multiple injections under cystoscopic guidance directly into the detrusor.

With this procedure, complete continence can be achieved in 40-to-80 per cent of patients, and bladder capacity improved by 56 per cent for up to six months. Maximal benefit is achieved between two and six weeks, maintained over six months. The injections can be repeated when needed according to the degree of improvement or relief of symptoms.

| DRUG | ROUTE | DOSE | RECEPTOR SELECTIVITY | MAIN METABOLISM | CNS PENETRATION |

| Oxybutynin | Oral, Transdermal patch Transdermal gel | 5mg bid-tid 5 or 10mg qd 3.9mg/day, twice weekly 1g (1 sachet) qd | Non-selective | Hepatic | High |

| Tolterodine | Oral | 2mg bid 4mg qd | Non-selective | Hepatic | High |

| Trospium | Oral | 20mg bid Age >70: 20 mg qd | Non-selective | Renal | Low |

| Solifenacin | Oral | 5 to 10mg qd | M3, M1 selective | Hepatic | High |

| Darifenacin | Oral | 7.5 to 15mg qd | M3 selective | Hepatic | Low |

| Fesoterodine | Oral | 4mg, 8mg | Non-selective | Hepatic | High |

Other options include posterior tibial nerve stimulation and sacral nerve stimulation. This involves an implantable electrode in the S3 foramen continuously stimulating the S3 nerve root, in order to stimulate the pudendal nerve. A temporary wire is initially placed (under local anaesthetic) for five-to-seven days in both sides, and a voiding diary should be kept. An improvement of >50 per cent in any parameters will enable a permanently implanted S3 lead on the side with the best clinical response. There is a potential benefit with this procedure of up to five years in patients with OAB.

Current indications for sacral nerve stimulation include refractory urge incontinence, refractory urgency and frequency, and idiopathic urinary retention.

Some more radical methods of treatment include augmentation cystoplasty and urinary diversion. In augmentation cystoplasty, the bladder is enlarged by incorporating a variety of different patches into the native bladder, usually patches of bowel still attached to their mesentery (ileum, caecum or sigmoid colon). Indications for bladder augmentation include a small, contracted bladder and a dysfunctional bladder with poor compliance.

Urinary diversion should be considered only when conservative treatments have failed, and if sacral nerve stimulation and augmentation cystoplasty are not appropriate or unacceptable to the patient. Urinary diversion involves rerouting the tubes that lead from the kidneys to the bladder (ureters). This allows the bladder to be bypassed and the tubes to be routed directly to the outside of the body through the abdominal wall. This means the urine does not f low into the bladder, but instead is collected in an ostomy bag worn on the abdomen. This intrusive procedure is only performed after all other treatment options have failed.

A study published in 2022 in Sec Geriatric Medicine suggests that radiofrequency (RF) therapy is a safe and effective treatment for OAB. The authors postulate that RF therapy is minimally invasive, inexpensive and effective and may provide benefits similar to when it is applied in other conditions. In a clinical trial, the authors applied a micro-RF therapy as a trans-urethral procedure using multi-polar ?RFthera technology delivering a maximum power of 2.5W to the bladder wall. The temperature was controlled under 45°C, which they suggest may reduce the sensitivity of the submucosal nerve endings of the bladder. The main treatment-related complications were catheterisation-related complications, they wrote.

SUMMARY

OAB is a common but bothersome condition that can have a significant effect on quality of life. Taking a thorough history and a targeted physical examination is imperative in reaching a diagnosis, along with other appropriate investigations. The role of behavioural therapy and lifestyle modifications is important, as these can have almost equal efficacy to pharmacological treatment.

Careful monitoring of the patient’s progress helps in addressing specific problems, and trying different methods if previous ones don’t work or have considerable side-effects is always an option.