Eamonn Brady MPSI provides a clinical overview of wound care

Pressure ulcers are lesions caused by unrelieved pressure that results in damage to the underlying tissue. Generally, these are the result of soft tissue compression between a bony prominence and an external surface for a prolonged period of time. Pressure ulcers are among the most common conditions encountered in patients in hospital or requiring long-term institutional care. American studies have shown that pressure ulcers also are common among patients admitted to nursing homes, with reported rates ranging from 10-to-35 per cent.1

Manifestations and Diagnosis

Pressure ulcers are usually easy to identify by their appearance and location overlying a bony prominence. It is important to distinguish pressure ulcers from ulcers that result from diabetic neuropathy or arterial or venous insufficiency.2 They also may be confused with other conditions that cause redness of skin, such as cellulitis. Superficial moisture-induced lesions, such as maceration (softening and whitening of skin) over a bony prominence, should not be labelled as pressure ulcers. Characteristics of lesions that need to be distinguished from pressure ulcers are:

- Diabetic neuropathic ulcers are seen in patients with diabetes who have peripheral neuropathy. The diabetic ulcer characteristically occurs on the foot, usually on the ball of the foot just behind the big toes or on the top of toes.

- Venous insufficiency ulcers are usually found on the inner part of the lower leg, usually just above the ankle. Approximately 70 per cent of all leg ulcers are venous ulcers. They can occur either on one or both legs and each leg may have more than one ulcer. They can range from painless, to extremely painful. These types of ulcers are common in people who have a history of leg and feet swelling. The ulcer usually presents itself as an open sore in an area that already typically exhibits a red-to-brown discoloration that has probably been present for some time. The area will also be swollen. Prior to the formation of the ulceration, the skin may have also been somewhat flaky and itchy. So long as there is no arterial disease, venous leg ulcers will benefit from elevation and compression dressings.

- Arterial ulcers occur as the result of arterial occlusive disease. Approximately 10 per cent of all leg ulcers are arterial ulcers. Feet and legs often feel cold and may have a whitish or bluish, shiny appearance. Arterial leg ulcers can be painful. Pain often increases when the legs are at rest and elevated.

Classification system

European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel grading system:5

- Grade 1: Redness that does not whiten on touch. Discolouration of the skin, warmth, oedema and hardness may also be used as indicators, particularly in individuals with darker skin, in whom it may appear blue or purple. Grade 1 may be more difficult to detect in those with dark skin tones.

- Grade 2: Partial skin thickness loss involving epidermis, dermis, or both. The ulcer is superficial and presents clinically as an abrasion or blister. Surrounding skin may be red or purple. If bruising is visible at this stage, it can indicate deep tissue injury.

- Grade 3: Full thickness skin loss involving damage to or necrosis of subcutaneous tissue. Subcutaneous fat may be visible, but tendon, muscle or bone are not exposed. Slough may be present.

- Grade 4: Extensive destruction, tissue necrosis, or damage to muscle, bone, or supporting structures with or without full thickness skin loss. Extremely difficult to heal and can lead to fatal infection.

Unstageable — Full thickness tissue loss in which the base of the ulcer is covered by slough (yellow, tan, gray, green or brown) and/or eschar (tan, brown or black) in the wound bed. Eschar often covers deep ulcers, making it difficult to determine whether lesions are stage 3 or 4. Until enough slough and/or eschar is removed to expose the base of the wound, the true depth, and therefore stage, cannot be determined.

Causes

External causes

There are external factors that contribute to pressure ulcers. The four main external factors that lead to the development of pressure ulcers are pressure, shearing forces, friction, and moisture.

- Pressure: Pressure applied to the skin in excess of the arteriolar pressure (32mmHg) prevents the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to tissues, resulting in tissue hypoxia, the accumulation of metabolic waste products, and free radical generation.7 Pressures are greatest over bony prominences where weight-bearing points come into contact with external surfaces. Extensive deep tissue damage may occur with little or no evidence of superficial tissue injury. A deep necrotic wound may be the first evidence of pressure-induced injury, rather than a gradual progression of an ulcer from stages 1 through 4.

- Shearing forces: Shearing forces occur when patients are placed on an incline. Deeper tissues, including muscle and subcutaneous fat, are pulled downwards by gravity, while the superficial epidermis and dermis remain fixed through contact with the external surface.

- Friction: Friction occurs when patients are dragged across an external surface. This results in an abrasion with damage to the most superficial layer of skin. It is less likely to cause stage 3 and 4 ulcers than pressure.

- Moisture: Exposure to moisture in the form of perspiration, faeces, or urine may lead to skin maceration and predispose to superficial ulceration. There is little evidence regarding the magnitude of the contribution of moisture to pressure ulcer development.9

Approximately 10 per cent of all leg ulcers are arterial ulcers. Feet and legs often feel cold and may have a whitish or bluish, shiny appearance

Patient-specific causes

- Patient factors that may contribute to pressure ulcer development include immobility, incontinence, nutritional status, circulatory factors, and neurological disease.

- Immobility: Immobility is the most important patient factor that contributes to pressure ulcer development.

- Incontinence: Urinary incontinence is frequently cited as a predisposing factor for pressure ulcers. Some studies suggest that incontinent patients have up to a five-fold higher risk for pressure ulcer development.10

- Nutritional status: Among patients in hospital and care home settings, body mass index below 25kg/m2 is associated with greater risk of pressure ulcer development.11

- Circulatory factors: The precise role of circulatory factors in pressure ulcer development must be further studied, although it appears likely that they have a major role. Factors which can exacerbate or cause circulation issues include hypotension, dehydration, vasomotor failure, vasoco striction secondary to shock, heart failure, or medications.

- Neurological diseases: Neurological diseases such as dementia, delirium, spinal cord injury and neuropathy are important contributors to pressure ulcer development. This may be related to immobility, spasticity, and muscle contractions that are common in these conditions. Sensory loss is also common, suggesting that patients may not perceive pain or discomfort arising from prolonged pressure. Peripheral neuropathy due to diabetes is an example where pressure sores can occur due to sensory loss.

Prevention

The European Pressure Ulcer Advisory

Panel made the following four points in relation to prevention of ulcers:6

- Skin injury due to friction and shear forces should be minimised through correct positioning, transferring and repositioning techniques.

- Eliminate any source of excess moisture due to incontinence, perspiration or wound drainage.

- Reduce underlying risk factors, such as poor nutrition.

- Education and training, ie, mobility, positioning, skin care, use of equipment, for patients and their carers.

PRESSURE RELIEF

Patient positioning

Proper positioning of bed-bound individuals is recommended, including a regular turning and repositioning schedule, with particular attention to vulnerable tissue covering bony prominences such as the sacrum.13 Typically, a two-hour interval is recommended.

In addition to regular turning, the position of bed-bound patients is likely to be important. It is recommended that:

- Patients should be placed at a 30-degree angle when lying on their side to avoid direct pressure over the hip bone or other bony prominences.

- Pillows or foam wedges should be placed between the ankles and knees to avoid pressure at these sites when patients have no mobility at these areas.

- The heels require particular attention; pillows may be placed under the lower legs to elevate the heels, or special heel protectors can be used.

- The head of the bed should not be elevated more that 30 degrees to prevent sliding and friction injury.

Chair-bound patients may generate considerable pressures over the hip joints; they should be repositioned at least every hour with wheelchair push-ups or with tilting of the seat to reduce contact between the patient’s buttocks and the seat.14 Patients who are cognitively intact and are able to use their upper extremities can be trained to shift weight even more frequently, using monitoring devices as a reminder.

Support surfaces (mattresses) — these products can be classified as either non-powered, overlays, or powered.

Non-powered support surfaces (previously known as static) do not require electricity and consist of mattresses that are made of gel, foam, air, or water, or a combination of these. They work by distributing pressure over a wider body surface area.

Overlays are support surfaces designed to be placed on top of another support surface. Foam, air, or water overlays may be used for patients who can assume a variety of positions without bearing weight on the ulcer.

Powered or dynamic support surfaces require electricity to alternate air currents in order to regulate or redistribute pressure against the body. Examples include alternating pressure mattresses, low air loss beds, and air fluidised mattresses. For chair-bound patients, appropriate wheelchair cushions are recommended. Donut cushions should not be used, as they increase oedema and venous congestion and concentrate the pressure to surrounding tissue.15 The three main types of seat cushions include gel and foam seat cushions, non-powered adjustable cushions and powered adjustable seat cushions.

Minimise immobility

Encouraging patient mobility is key to the prevention of pressure ulcers. Several approaches may be helpful to minimise immobility, including:

- Immobilised patients may benefit from physiotherapy.

- Severe spasticity may be relieved by muscle relaxant drugs, ie, Lioresal or nerve block.

- Medications contributing to immobility, such as sedatives, should be stopped.

Management1

- Repositioning of the patient.

- Treatment of concurrent conditions which may delay healing, ie, poor circulation

- Pressure-relieving support surfaces such as beds, mattresses, overlays or cushions.

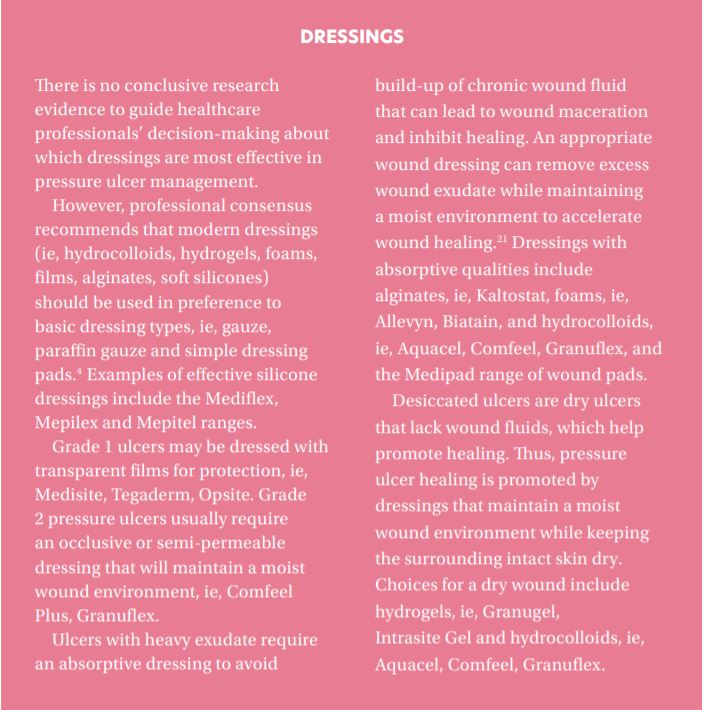

- Local wound management using modern or advanced wound dressings and other technologies.

- Patients with identified grade 1 pressure ulcers are at a significant risk of developing more severe ulcers and should receive interventions to prevent deterioration.

Pain relief

- Pain is often significant and disabling for those with pressure ulcers.

- Paracetamol may be sufficient, but patients often require stronger analgesia.

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may increase peripheral oedema and are inappropriate for patients with pressure ulcers, ie, Ibuprofen, Diclofenac.

- Opioid analgesics may be needed for moderate-to-severe pain.

- Topical local anesthetics such as lidocaine can provide numbness for a short period of time and can be useful for a specific procedure, but should not be used as the only method of pain relief.

- Wound-cleansing and dressing techniques may need to be reconsidered if they are causing severe pain. In particular, adequate pain control should be provided for dressing changes and debridement.

- Patients may require referral to a pain clinic.

Nutrition

If oral intake is not adequate to ensure sufficient calories, protein, vitamins, and minerals, nutritional supplementation with enteral and parenteral nutrition (PEG feed) is recommended to correct deficiencies.19-20 Increased dietary protein intake promotes the healing of pressure ulcers. The protein target is usually 1.5g/kg/day. Cubitan is an example of a high-energy, high-protein oral nutritional supplement (ONS) with wound-specific nutrients (arginine, vitamin C, zinc, vitamin E). It increases healing times of pressure sores in undernourished patients. However, it is important that oral nutritional supplements are reviewed regularly by a dietitian. While high-protein ONS such as Cubitan have an important role in helping heal ulcers and other wounds, they should be discontinued promptly once the wound has healed. Food is the best vehicle for appropriate nutrient consumption.22 According to the National Medicines Information Centre in St James’s Hospital, Dublin, no studies have yet determined the optimum usage of ONS in terms of the most appropriate patients, the optimum dose and duration of use.23 Despite lack of evidence, ONS has a role in many circumstances; therefore, it is important to liaise with nutrition specialists such as dieticians before ONS can be recommended. For the added reason of the high cost of ONS to the State, the HSE also recommends that ONS is only commenced after the patient is assessed by a dietician.

Debridement

Necrotic tissue promotes bacterial growth and impairs wound healing. Wound debridement may involve any of five approaches: use of sharp dissection (take care when doing this on heels), mechanical debridement (wet-to-dry dressings), application of proteolytic enzymes, autolytic debridement under occlusive dressings (hydrocolloids or hydrogels), or biosurgery with sterilised maggots.

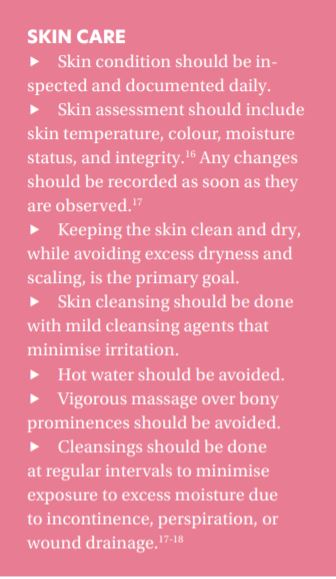

Skin assessment should include skin temperature, colour, moisture status, and integrity. Any changes should be recorded as soon as they are observed

Infection control

- Reduce risk of infection and enhance wound healing by hand-washing, wound-cleansing and debridement. Protect from external sources of contamination, ie, faeces.3

- If purulent material or foul odour is present, more frequent cleansing and possibly debridement are required.

- When there are clinical signs of infection which do not respond to treatment, x-rays should be undertaken to exclude osteomyelitis and joint infection.3

- Systemic antibiotics are required for patients with bacteraemia, sepsis, advancing cellulitis or osteomyelitis.3

References

- Pressure ulcers in America: Prevalence, incidence, and implications for the future: An executive summary of the national pressure ulcer advisory panel monograph. Adv Skin Wound Care 2001; 14:208.

- European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel; Pressure Ulcer Grading System. 2003.

- Bergstrom N, Braden B, Kemp M, et al; Predicting pressure ulcer risk: A multisite study of the predictive validity of the Braden Scale. Nurs Res. 1998 Sep-Oct;47(5):261-9. [abstract].

- Pressure ulcers: The management of pressure ulcers in primary and secondary care, NICE Clinical Guideline (2005).

- Thomas DR, Goode PS, Tarquine PH, et al; Hospital-acquired pressure ulcers and risk of death. J Am Geriatric Soc. 1996 Dec;44(12):1435-40. [abstract].

- European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel; Pressure Ulcer Prevention Guidelines. 2003.

- Kosiak, M. Etiology of decubitus ulcers. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1961; 42:19.

- Nola, GT, Vistnes, LM. Differential response of skin and muscle in the experimental production of pressure sores. Plast Reconstr Surg 1980; 66:728.

- Cooney, LM Jr. Pressure sores and urinary incontinence. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997; 45:1278.

- Lowthian, PT. Underpads in the prevention of decubiti. In: Bedsore biomechanics, Kenedi, RM, Cowden, JM, Scales, JT (Eds), University Park Press, Baltimore, MD 1976. p.141.

- Berlowitz, DR, Brandeis, GH, Morris, JN, et al. Deriving a risk-adjustment model for pressure ulcer development using the Minimum Data Set. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001; 49:866.

- Makhsous, M, Priebe, M, Bankard, J, et al. Measuring tissue perfusion during pressure relief maneuvers: insights into preventing pressure ulcers. J Spinal Cord Med 2007; 30:497.

- Reddy, M, Gill, SS, Rochon, PA. Preventing pressure ulcers: a systematic review. JAMA 2006; 296:974.

- Makhsous, M, Priebe, M, Bankard, J, et al. Measuring tissue perfusion during pressure relief maneuvers: insights into preventing pressure ulcers. J Spinal Cord Med 2007; 30:497.

- Stechmiller, JK, Cowan, L, Whitney, JD, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of pressure ulcers. Wound Repair Regen 2008; 16:151.

- Lyder, CH, Ayello, EA. Chapter 12. Pressure ulcers: a patient safety issue. Available online at: www.ahrq.gov/qual/nurseshdbk/docs/LyderC_PUPSI.pdf – 2008-03-11 (Accessed on October 10, 2008).

- European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP). Guidelines on treatment of pressure ulcers. EPUAP Review 1999; 1:31.

- Pressure ulcers in adults: Prediction and prevention. Clinical Practice Guideline Number 3, AHCPR Publication no. 92-0047, May 1992.

- Allman, RM, Walker, JM, Hart, MK, et al. Air-fluidized beds or conventional therapy for pressure sores. A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 1987; 107:641.

- Breslow, RA, Hallfrisch, J, Guy, DG, et al. The importance of dietary protein in healing pressure ulcers. J Am Geriatr Soc 1993; 41:357.

- Schultz, GS, Sibbald, RG, Falanga, V, et al. Wound bed preparation: A systematic approach to wound management. Wound Repair Regen 2003; 11 Suppl 1:S1.

- Tripp F, The use of dietary supplements in the elderly: Current issues and recommendations J Am Diet Assoc 1997; 97(suppl 2): S181-S183.

- National Medicines Information Centre, St James Hospital, Dublin 8. Volume 10, Number 2. The role of oral nutritional supplements in primary care. 2004

Disclaimer: Brands mentioned in this article are meant as examples only and not meant as preference to other brands.

Written by Eamonn Brady MPSI (Pharmacist) owner of Whelehans Pharmacies, 38 Pearse St and Clonmore, Mullingar. Tel 04493 34591 (Pearse St) or 04493 10266 (Clonmore). www.whelehans.ie