Little attention in the current euthanasia debate has been paid to the role of Irish pharmacists and legislators and policy-makers need to be aware that the role of pharmacists goes far beyond supply of the required medication. Writing for Irish Pharmacist, Bernadette Flood MPSI examines the issues

The so-called Dying with Dignity Bill 2020 (Bill 24 of 2020) is a private members Bill introduced to the Oireachtas in 2020. Formally titled ‘Bill entitled an Act to make provision for assistance in achieving a dignified and peaceful end-of-life to qualifying persons and related matters’, the Bill is currently before Dáil Éireann, Third Stage: https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/bills/bill/2020/24/. This article does not address the many and complex moral, religious, ethical, philosophical, medical and other issues associated with assisted suicide and euthanasia and is written from one pharmacist’s perspective.

Introduction

In jurisdictions where euthanasia and/or assisted suicide is legal, experience shows there are profound implications for pharmacy practice. Little attention in the current euthanasia debate has been paid to the role of Irish pharmacists. Pharmacists are employed in the Irish healthcare system in a variety of locations: Hospital, long-term care, care of vulnerable populations, community, academia/research, education, industry, palliative care/hospice care, legislation, policy, drug information, HIQA, etc. All may be challenged professionally and personally if euthanasia and assisted suicide are introduced.

Medicines are the most common healthcare intervention within the health system and the use and complexity of medicines are increasing. Pharmacists are the healthcare professionals with the widest knowledge of medicines and the potential complexities associated with the increasing use of medicines. Pharmacy as a profession has, therefore, a critical role to play within the health system to ensure the rational use of medicines by maximising the benefits and minimising the potential for patient harm with regard to medicines.

The intertwining of poison and healthcare is a long-standing concept in the therapeutic use of medicines. When it comes to the question of which medicines can, or even are meant to, kill us, the most important thing to remember is the adage, ‘the dose makes the poison’. This concept is one on which the disciplines of toxicology, pharmacy and medicine are founded.

During the current debate on euthanasia and assisted suicide, the impact a change in the law may have on pharmacy in Ireland could be overlooked. Pharmacists are in a critical position when pharmaceutical agents, ie, medicines, are prescribed for the purpose of assisted suicide and/or euthanasia. In the medication use process (see Figure 1), pharmacists would have a special responsibility to protect patients who contemplate end-of-life decisions such as assisted suicide and euthanasia. Pharmacists may view their professional responsibility in assisted suicide to be more obligatory than a physician’s, in having to provide the means for physician-assisted suicide.

In the main, Irish pharmacists may not be privy to certain aspects of the doctor/patient relationship, patient diagnosis and therapeutic decision-making that would play an essential role in the end-of-life decision process. No medications are uniquely indicated for euthanasia and assisted suicide and many medications used are outside their product licence. It is unclear from the Dying With Dignity Bill 2020, currently being examined by the Oireachtas Committee on Justice, if the pharmacist will be made aware of the purpose of the prescription for lethal medications.

Pharmacists will have the responsibility of stocking, storing, handling, dispensing, safe keeping and overseeing the ethical, legal and safe supply of medicines, including those prescribed for euthanasia and assisted suicide. Pharmacists will be asked for advice and information on lethal medications, lethal doses of medications and safe disposal of lethal medications.

Pharmacists will also be asked to assist in relevant guideline preparation. At a time in Canada when assisted suicide and euthanasia had been legal for eight months, one-third of pharmacy respondents had dispensed a prescription for its use. (This finding was from a survey with 1,040 valid survey responses, with respondents consisting of 607 pharmacists, 273 pharmacy technicians, and 160 pharmacy assistants). Legislators and policy-makers need to recognise and be aware that the role of pharmacists goes far beyond supply of the required medication.

Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians/assistants dispensing prescriptions that may be used in assisted suicide and euthanasia will be required to counsel patients and families about these prescriptions and the use, safety, and disposal of lethal medications. In many jurisdictions (including the Canadian Northwest Territories, the Yukon, and New Brunswick), the medications required for assisted suicide and euthanasia are provided by hospital pharmacies, whether the medications are to be administered at a hospital or in the home.

Pharmacists may have responsibility for quality assurance of aspects of the medication use process for lethal medications. Canadian research has identified four sub-themes of quality assurance: Preparation and adaptation of medications; storage of medications; destruction of medications and management of documentation received from the prescriber; as well as paperwork related to any aspects of the assisted suicide and euthanasia process for which they are involved.

Pharmacy students in the future may have to exhibit ‘competency’ relating to medication choice, and their effectiveness and efficiency during the assisted suicide and euthanasia process. Pharmacy students will require education on the effects and side-effects of lethal medications so that they can advise the ‘optimum’ medicines if intentional ending of human life is the envisaged objective of the prescriber. There will be important implications for ethics, law, medicine and pharmacy if defining an ‘optimum’ medication to be used in assisted suicide and euthanasia.

End-of-life care

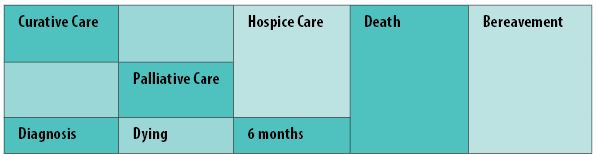

Patients and families deserve the best possible care when faced with a life-limiting illness and rapidly-changing life circumstances (see Figure 2). Irrespective of the delivery setting and models of care, clinicians should be able to quickly and confidently work with the available evidence to provide much-needed symptom relief and support.

Palliative care arose from the modern hospice movement and has evolved significantly over the past 50-to-60 years. Patients who receive palliative care are heterogeneous, with vastly different underlying personal needs, medical histories, symptom concerns and family and caregiver support.

Equally, their situations are influenced by external factors, such as living environment, health system resources, formal and informal services, and access to care. Their resultant needs and preferences for care, and those of their families and carers, are diverse.

As the model of palliative care has progressed, so too has each team member’s potential for contribution. The World Health Assembly has resolved that palliative care is “an ethical responsibility of health systems” and that integration of palliative care into public healthcare systems is essential for the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goal on universal health coverage.

The Irish Palliative Care Competence framework describes core competences and discipline-specific competences for 12 health and social care disciplines, including pharmacy. The World Health Organisation (WHO) recognises that basic palliative care can prevent or relieve most suffering due to serious or life-threatening health conditions and can be taught easily to generalist clinicians, can be provided in the community, and requires only simple, inexpensive medicines and equipment.

Palliative care is explicitly recognised under the human right to health. It should be provided through person-centred and integrated health services that pay special attention to the specific needs and preferences of individuals. However, the WHO has noted that worldwide, only about 14 per cent of people who need palliative care currently receive it. There is an urgent need for adequate national policies, programmes, resources, and training on palliative care among health professionals to improve access.

Dr Els Borst, a doctor and health minister who guided the euthanasia legislation through the Dutch parliament, stated in 2009 that there had not been enough attention given at the time to palliative care and support for the dying. (Differences exist in the palliative and end-of-life care services available in different regions, which may affect professionals’ attitudes regarding assisted suicide and euthanasia.)

Patients at the end-of-life can suffer from depression, anxiety, guilt, stress, worthlessness, paranoia, fear, and even suicidal thoughts and attempts. It is important to address these issues and offer help as soon as a problem is found. Early involvement of a psychiatrist and the provision of spiritual support is associated with improved mental health and a better quality of life.

Being symptom-free is one of the most important factors for patients when considering end-of-life care. Pharmacists have much to offer, not only in providing medicines required for symptom management, but also supporting patients and their carers to receive the right care at the right time. Pharmacists, with their extensive knowledge of therapeutic options to manage palliative symptoms, may lessen the likelihood of pharmacists considering death as the best option for patients who might consider assisted suicide and euthanasia.

Administration of ‘a pill’

Many healthcare professionals, politicians and members of the general public who support the introduction of assisted suicide and/or euthanasia may be under the impression that the method of dying they support would be achieved by the administration of ‘a pill’. This is not the case. Many promoters of assisted suicide and/or euthanasia often suggest that the use of medications during the assisted dying process results in a pain-free, dignified death for all.

This is not the case. Modern medicine cannot guarantee a pain-free death (natural or intentional) for all. Unrealised goals for ideal oral medication use during assisted suicide and/or euthanasia are 100 per cent effectiveness and minimal side-effects, while ensuring that the needed dose is both palatable and deliverable in a tolerable oral volume in assisted suicide.

The characteristics and frequency of clinical problems with the performance of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide have not been discussed in Ireland. For all forms of assisted dying, there appears to be a relatively high incidence of vomiting (up to 10 per cent), prolongation of death (up to seven days), and re-awakening from coma (up to 4 per cent), constituting failure of unconsciousness.

In the Netherlands, complications occurred in 7 per cent of cases of assisted suicide, and problems with completion (a longer-than-expected time to death, failure to induce coma, or induction of coma followed by awakening of the patient) occurred in 16 per cent of the cases; complications and problems with completion occurred in 3 per cent and 6 per cent of cases of euthanasia, respectively. The physician decided to administer a lethal medication in 21 of the cases of assisted suicide (18 per cent), which thus became cases of euthanasia. Studies in The Netherlands show that non-reporting of euthanasia is strongly related to the type of drugs used.

Many deaths during assisted suicide are prolonged.

Patients may become unconscious relatively quickly but the dying process can take up to 30 hours or more. There are also reports of people re-emerging from a coma and sitting up during the dying process. It is important that the correct drugs are chosen. Failure to use the ‘correct drugs’ in the assisted suicide and/or euthanasia process may lead to traumatic situations, such as an extended time to death or awakening of the patient, causing distress for the patient and the attending family and healthcare providers. In a study involving physicians in Flanders, Belgium, one-third of cases of euthanasia identified between 1998 and 2013 involved the use of ‘non-recommended drugs’, mainly opioids or benzodiazepines.

There is currently an international scarcity of lethal drugs suitable for oral administration during an assisted suicide. On occasions when oral barbiturate drugs are administered, there are reports of patients being unable to self-administer a complex cocktail of lethal medicines. Family members have reported having to scrape powder from 100-plus capsules with toothpicks to produce bitter powder to be mixed with sugar syrup. Medication for nausea and vomiting must be consumed before and during the process. In some countries, lethal cocktails have been ‘experimented’ with due to difficulties sourcing licensed medicines for the purpose of assisted suicide and/or euthanasia. “… Proposed product would need to be tested and results compared, as all new drugs are”.

A scoping review of the 163 studies that included technical summaries, institutional policies, practice surveys, practice guidelines and clinical studies that describe assisted suicide and/or euthanasia provision in adults identified complications that may cause patient, family and provider distress. These included prolonged duration of the dying process, difficulty in obtaining intravenous access, and difficulty in swallowing oral agents.

Since 2016, intravenous euthanasia has been the main form of delivery of assisted death in Canada.

Oral-assisted suicide is under-utilised in Canada, as there is no international consensus on either the medications or the protocols for oral administration, nor a comprehensive understanding of the potential side-effects and complications associated with different regimens. The quality of evidence for ‘optimal’ assisted suicide medications is low. It is recognised that any suggested recommendations can only be informed by the global but generally anecdotal experience. There are challenges for implementing oral assisted suicide in Canada (and elsewhere?).

Freedom of conscience

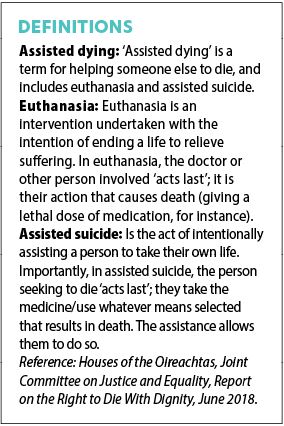

A range of euphemisms are commonly used to avoid the terms ‘euthanasia’ and ‘assisted suicide’. These may include ‘death with dignity’, ‘medical assistance in dying’, ‘peaceful alternative’, ‘mercy killing’, etc. These do not alter the gravity of the act, ie, the intentional killing of a human being.

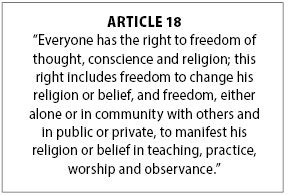

Conscientious objection is a right derived from the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion, as set out in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The right to conscientious objection is not a right per se, since international instruments of the United Nations do not make direct reference to such a right, but rather is normally characterised as a derivative right; a right that is derived from an interpretation of the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion.

Irish pharmacists and pharmacy students are excluded from protection of their right to freedom of conscience/conscientious objection in the Health (Regulation of Termination of Pregnancy) Act 2018. Doctors and nurses and their students are included in the Conscientious Objection section of the Act. This unequal treatment makes individual pharmacists and the profession of pharmacy vulnerable.

Unequal treatment of pharmacists is also evident in the exclusion of pharmacists in the Conscientious Objection section (Section 13) of the so-called Dying with Dignity Bill 2020. This unequal treatment perpetuates the vulnerability of pharmacists and pharmacy. Doctors and nurses (and others) are included in the Conscientious Objection section. It is unclear why pharmacists are excluded. The inclusion of one group excludes all groups not included. The exclusion of pharmacists fails to recognise their dignity as human beings: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.”

As a universal human right, an individual pharmacist’s right to freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief must be interpreted strictly in keeping with the opening sentence of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and similar provisions. Hence it is not that the Irish State could ‘grant’ an individual pharmacist, certain individuals or groups of individuals this right. Rather, it is the other way around: The Irish State has to respect the individual pharmacist’s freedom of religion, conscience or belief as an inalienable — and thus non-negotiable — entitlement of the pharmacist and other human beings, all of whom have the status of right-holders in international law by virtue of their inherent dignity.

Restrictions of human rights can only be permissible if they are legally prescribed and if they are clearly needed to pursue a legitimate aim. Freedom of conscience and the free profession and practice of religion are guaranteed in the Irish Constitution (Bunreacht na hÉireann) to every citizen, subject to public order and morality (article 44.2.1) and the State must not impose any disabilities or make any discrimination on the ground of religious profession, belief or status (article 44.3). These and the other provisions of article 44 show a combination of respect for different religious denominations and non-discrimination between them.

The UN General Assembly has expressed concerns at the increasing number of laws and regulations that limit the freedom of thought, conscience and religion or belief and at the implementation of existing laws in a discriminatory manner. It has also strongly condemned violations of freedom of thought, conscience and religion or belief, as well as all forms of intolerance, discrimination and violence based on religion or belief.

Conclusion

The current legislation before Dáil Éireann governing assisted suicide/euthanasia poses challenges for pharmacists, given their central role in medication governance and administration within the healthcare system. All forms of euthanasia and assisted suicide require lethal medications. Pharmacists are potentially faced with dispensing medication that is intended to kill, and of consulting with patients, family members and medical colleagues, on associated issues. They may be expected to do so in a context in which there is limited evidence and with which they are morally opposed.

The work done by pharmacists and pharmacy teams across all settings during 2020, to support patients and the public throughout the pandemic and to reduce the health impact of the crisis, testifies to the professionalism and commitment of all involved.

The professionalism, commitment and expertise of pharmacists and their teams have been recognised. It is important that their dignity as human beings will be similarly recognised and respected.

The individual pharmacist and the profession of pharmacy should be considered in all debates on euthanasia and physician-assisted dying. Regardless of one’s own perspective on the morality of the Bill, pharmacists have a human and constitutional right to freedom of conscience, and this must be reflected in the same legislative safeguards afforded to other professions.

Full references on request

Bernadette Flood is a pharmacist who has worked with people with intellectual disabilities and their carers for more than 20 years. This challenging and rewarding experience has stimulated an interest in the protection of human rights for vulnerable populations and vulnerable professionals.