An overview of the main factors in caring for patients with lung and breast cancer, including the vital role of the pharmacist

The impact of Covid-19 on healthcare services has meant that many cancer diagnoses may have either been missed or delayed, although it will take time before estimates of the actual figures emerge. In this regard, the pharmacist has an important role to play in helping patients recognise the more obvious symptoms and suggest they visit their doctor urgently. In addition, the pharmacist plays a vital role in helping patients undergoing cancer treatment to manage their medications and it has been shown that the addition of a pharmacist to the cancer care team improves mortality rates, as described later in this article.

Incidence

Breast cancer is among the most common cancer in women, with approximately 3,700 new cases diagnosed annually. Overall, one-in-nine women will be affected by breast cancer in their lifetime and 30 per cent of women are diagnosed between the ages of 20-to-50 years. Only five-to-10 cases of breast cancer are hereditary and while 34 per cent of women are diagnosed between the ages of 50-to-69 years, 36 per cent receive a diagnosis when they are over the age of 70 years.

Thanks to improved screening, enhanced treatment options and greater awareness, mortality rates are decreasing by approximately 2 per cent annually. Around 690 women die annually from breast cancer, but the goal is to transform the condition from being a fatal one, to a treatable long-term illness.1

Lung cancer remains among the most common cancer diagnoses in Ireland for both men and women and nine out of 10 cases are caused by smoking, with half of all smokers dying from a tobacco-related disease. Lung cancer is the fifth-most common cancer in Ireland overall and a diagnosis is usually made over the age of 50 years. Approximately 2,700 new cases of lung cancer are diagnosed annually in Ireland.2

Prevention and early detection

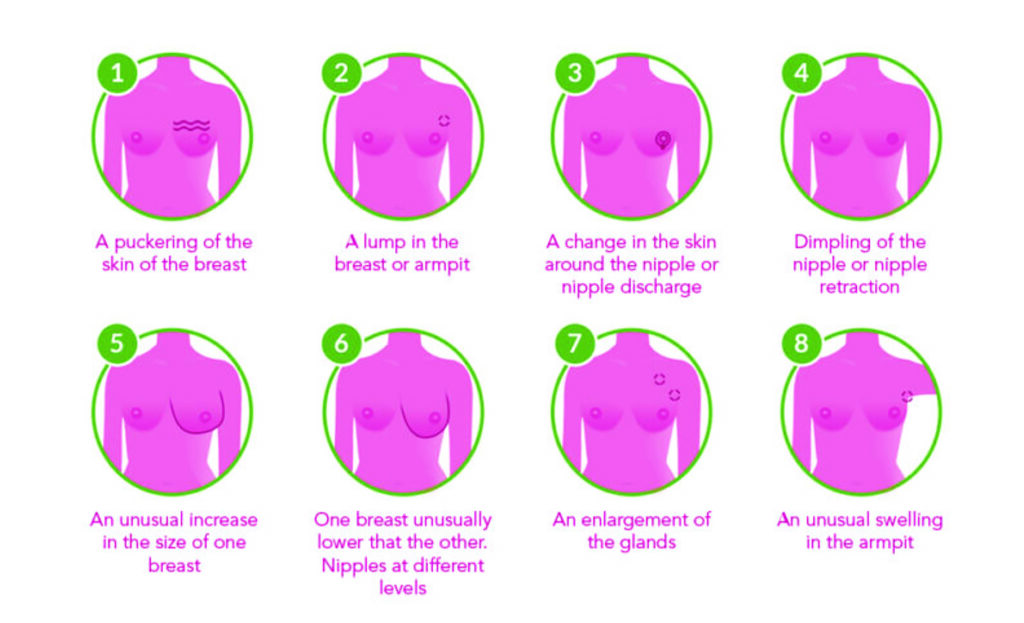

As with any cancer, early diagnosis is crucial in order to minimise the risk of mortality and optimise treatment. While awareness around breast cancer is improving, some patients may present at the counter seeking analgesics for a pain that may be associated with breast cancer. The most common symptoms of breast cancer are outlined in Figure 1.

As well as the indicators in Figure 1, Cancer Research UK states that suspicion should also be raised if the nipple leaks fluid in a woman who is not pregnant or breastfeeding or if there are changes in the position of the nipple. These symptoms may be due to other conditions but if any of these are present, women should be urged to see their GP as soon as possible.

Similarly, the early symptoms of lung cancer can easily be confused with other less serious conditions. According to the Irish Cancer Society, the common symptoms of lung cancer include:

- Difficulty breathing.

- A cough that doesn’t go away or a change in a long-term cough.

- Repeated chest infections that won’t go away, even after antibiotics.

- Feeling more tired than usual.

- A hoarse voice.

- Coughing up bloodstained phlegm.

- Pain in the chest, especially when coughing or breathing in.

- Loss of appetite/weight loss.

- Swelling around the face and neck.

- Difficulty swallowing.

The Society also points out that while smoking is the most obvious and causative factor in lung cancer, other risk factors include passive smoking; air pollution (some countries are more affected than others); exposure to radon gas; exposure to chemicals such as asbestos, uranium, metal dust and fumes, nickel, paints, diesel exhaust and nitrogen oxides; and family history (risk is doubled if parent, brother or sister had cancer that started in the lung).

The most effective way to lower the risk of lung cancer is to quit smoking, ideally with the help and advice of a pharmacist.

The risk of breast cancer can be lowered by staying physically active and limiting alcohol intake to one drink per day. Maintaining a healthy weight also reduces the risk of breast cancer and it has been postulated that breastfeeding may reduce the risk of breast cancer.3

Rare breast cancers

Male breast cancer: Men also have breast tissue and ducts behind the nipple but breast cancer in men is rare, with approximately 25 men diagnosed with the condition each year in Ireland. Factors that increase the risk for men include significant family history or genetic link; prolonged exposure to radiation, especially at a young age; Klinefelter syndrome, in which a man is born with an extra female chromosome; high oestrogen levels; obesity; and age over 60 years. Common symptoms include a painless lump in the nipple, discharge from the nipple which may be blood-stained, a tender or depressed nipple, ulceration, or swollen lymph glands under the arm. Treatment for male breast cancer is the same as for women.4

Inflammatory breast cancer: This is another rare form of cancer where symptoms can be different from more common forms of breast cancer. For example, the entire breast may look red and inflamed and feel sore, or the breast might feel hard and the skin might have an orange peel-type appearance.

Paget’s disease of the breast: A rare skin condition that may be a symptom of underlying breast cancer that can appear similar to eczema and present as a red, scaly nipple rash also affecting the surrounding area.5

Treatments

Treatments for lung cancer must be personalised and will depend on the type and extent of the cancer and whether it has metastasised. Non-small cell lung cancer can be treated with:

- Surgery. To remove the part of the lung containing cancer, or even an entire lung.

- Systemic drug treatments. Systemic anti-cancer drug therapies distribute themselves throughout the body to treat

- cancer cells wherever they are. These treatments include chemotherapy, targeted drugs and immunotherapy.

- Chemotherapy. This is designed to slow down and control the growth of cancer. Increasingly, this type of therapy is tailored to each patient, based on their type of cancer, and can be administered before or after surgery or given together with radiotherapy (known as chemoradiation).

- Targeted therapies. Most targeted drugs are administered in tablet or capsule form. These medications target specific genetic mutations in cancers. The type used for lung cancer usually works by blocking the signals that tell cancer cells to grow and divide, and physicians test tissue taken from a tumour to determine whether the cancer will respond to a particular targeted therapy (mutation testing).

- Immunotherapy. This helps the patient’s immune system to be more effective in fighting cancer cells.

- Radiotherapy. Can be used alone or with other therapies to treat NSCLC and can also be used to control certain symptoms, for example pain or breathlessness. Includes stereotactic radiotherapy.

- Radio frequency ablation and microwave ablation. These treatments employ heat to treat very early-stage lung cancers for people in whom surgery is not desired or possible. Also administered to relieve breathlessness if the tumour is blocking an airway.4

- Small-cell lung cancer can be treated using:

- Chemotherapy. Chemotherapy with radiotherapy is considered the main

- treatment for limited disease small-cell lung cancer.

- Radiotherapy. External beam radiotherapy uses high-energy rays to destroy cancer cells and stereotactic radiotherapy is a more precise way to administer radiotherapy.

- Surgery. This is rarely used for small-cell lung cancer.

- Metastatic cases. Metastases are often treated with chemotherapy, immunotherapy or targeted therapies.4

Role of the pharmacist

The importance of the pharmacist, either as part of a multidisciplinary team or as a support for cancer patients in the community, has been increasingly recognised in recent years and has been reinforced by research.

One of the most important tasks is in helping to promote medication compliance. This can include: Explaining how the medication works; reinforcing how the medication is to be taken; reviewing potential side-effects; and recommending financial resources.

The pharmacist is also the best-qualified healthcare professional to help patients manage their cancer pain while avoiding interactions with other medications they may be taking. The National Cancer Control Programme (NCCP) has designed the ‘National Competency Framework for Pharmacists Working in Cancer Care’, which was developed in collaboration with the Irish Pharmacy Union, Irish Institute of Pharmacy, community pharmacists and hospital oncology pharmacists. The HSE stated:

Another study from 2016 examined the pharmacist’s role in lung cancer care within a multidisciplinary team

“It is hoped that this framework will inform the development and provision of training for pharmacists working in cancer care. In addition, it will improve the quality of care and improve outcomes for cancer patients by illustrating the behaviours, skills and knowledge pharmacists require for working in cancer care.”

The document providing details of the Competency framework is available at www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/5/cancer/profinfo/training/pharmacist%20cancer%20care%20competency%20frameword.pdf.

Providing healthcare for older women can be complex because of polypharmacy considerations, as well as a progressive decline in their organ function. This has the potential to reduce the elimination of cancer drugs through renal excretion and liver metabolism, which increases the risk of side-effects and treatment-related toxicities, in addition to normal tissue tolerance.

As part of the multidisciplinary team, the clinical pharmacist provides specialist expertise on a given cancer treatment’s pharmacokinetic properties, including drug absorption, volume of distribution, liver metabolism and renal elimination to enable the best treatment pathway. As well as advice on drug-drug interactions, the pharmacist plays a vital role in imparting knowledge on drug–gene and drug–disease interactions, as well as conducting medications reconciliations that are vital to a patient’s wellbeing and survival.

Other important expertise pharmacists provide to cancer patients include the areas of pain management; constipation and diarrhoea; alleviating nausea and vomiting; treating or preventing anaemia; anticoagulation advice; and recommendations for treatment with anti-infectives. One significant complication in older patients is that elderly patients who are receiving chemotherapy for advanced or hormone receptor-negative breast cancer are at increased risk of developing myelosuppression secondary to their anti-cancer regimen. Clinical pharmacists can use laboratory monitoring to help identify patients who should be prescribed hematopoietic growth factors to decrease the myelotoxicity associated with chemotherapy.6

A study published in 2020 looked at 60 breast cancer patients at the Clinical Oncology Department, Ain Shams University Hospitals, Egypt, from June 2017 to May 2018. The prospective study was designed to assess whether the pharmacist’s intervention could improve clinical outcomes for patients with breast cancer. The authors stated:

“The present study has shown that the clinical pharmacist interventions were associated with significant decrease of toxicity grades of patients, for example, anaemia where the percentage of patients of grade 2 decreased from 17% to 1.7%; moreover, 5% of patients had grade 4 nausea/vomiting, while after pharmacist intervention, it became 0%. Regarding patients’ QOL, results of the present study showed improvement of mean ± standard deviation of most of the QOL scales, such as systematic therapy side-effects decreased from 80.8 ± 19.53 to 42.8 ± 16.8, all with P < 0.001.”7

Another study from 2016 examined the pharmacist’s role in lung cancer care within a multidisciplinary team. The study involved 48 patients and a specialist pharmacist was added to the oncology care team for six months, with a total of 154 pharmacist interventions during that time. Similar positive data emerged from the study and the authors concluded: “Adding a specialist cancer pharmacist to the outpatient lung cancer team led to significant improvements in patient medication adherence. Both patients and GPs were highly satisfied with the service. Medication misadventure and clinic attendances were reduced.”8

References

- Breast Cancer Ireland: Facts and Figures. https://www.breastcancerireland.com/education-awareness/facts-and-figures/, accessed Apr 2021.

- Irish Cancer Society: Lung Cancer. https://www.cancer.ie/cancer-information-and-support/cancer-types/lung-cancer#about, accessed Apr 2021.

- Mayo Clinic: Women’s Health. www.mayoclinic.org.

- Irish Cancer Society. www.cancer.ie.

- Cancer Research UK. Breast Cancer: Symptoms. www.cancerresearchuk.org.

- PharmD Live: Clinical Pharmacists’ Role in Breast Cancer Treatment for Older Women. www.pharmdlive.com, accessed Apr 2021.

- Farrag et al, Evaluation of the clinical effect of pharmacist intervention. European Journal of Oncology Pharmacy, January-March 2020 – Volume 3 – Issue 1 – p e23, doi: 10.1097/OP9.0000000000000023.

- Walter C et al, Impact of a specialist clinical cancer pharmacist at a multidisciplinary lung cancer clinic. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25227909/, 2016 Sep;12(3):e367-74. doi: 10.1111/ajco.12267.