A vulnerable profession

Pharmacists worldwide in all areas of the profession have fallen through the cracks of the legal protection of conscience when it comes to euthanasia and assisted suicide, writes Dr Bernadette Flood (PHD) MPSI.

Introduction

Euthanasia and assisted suicide are associated with the administration of lethal medications and/or lethal doses of medications. Pharmacists are pivotal to the euthanasia and assisted suicide process, as the process cannot occur without medications Pharmacists in Great Britain have viewed their professional responsibility in euthanasia and assisted suicide to be more obligatory than a physician’s, in having to provide the means for euthanasia/assisted suicide.

The process is complex, involves a number of actors, involves a number of stages, engages morality, ethics, philosophy, law, medicine, pharmacy, religion, politics, human rights, etc. The outcome of the process is the intentional termination of human life. The three health professions whose roles in ‘assisted dying’ provision are most often described in the scientific literature are physicians, nurses, and pharmacists. If legislation to introduce euthanasia and assisted suicide is passed in Ireland, every pharmacist would need to make a personal decision on whether or not they would wish to be involved in providing or supporting a service resulting in the intentional ending of human life.

This article is an Irish pharmacist’s reflection on some (limited) aspects of this complex grave topic.

Background

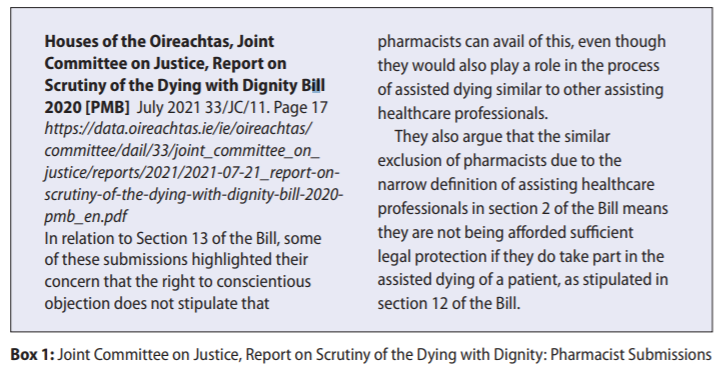

The Dying with Dignity Bill 2020 was introduced in the Dáil by opposition deputies Gino Kenny, Mick Barry, Richard Boyd Barrett, Paul Murphy and Bríd Smith in 2020 and was voted to committee stage. The Justice Committee then carried out scrutiny of the Bill, including seeking public submissions on the topic. Over 1,400 public submissions, including a number from pharmacists (Box 1), were received by the deadline in January 2021. The Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission (IHREC) has warned that the Bill did not ensure “adequate safeguards” to protect a person’s right to life.In July 2021, the Justice Committee Cathaoirleach James Lawless TD said the committee has determined that the Bill has “serious technical issues in several sections”, that it may have unintended policy consequences, and that the drafting of several sections of the Bill contains “serious flaws”.

It was decided that the Bill should not progress to Committee Stage, but that a Special Oireachtas Committee should be established, at the earliest convenience, for detailed consideration. This committee is expected to commence in early 2022. If enacted, the so-called Dying with Dignity Bill 2020 would have introduced euthanasia and assisted suicide (ie, the intentional termination of human life/killing) to Ireland.

The Dying with Dignity Bill 2020 was a simple six-page document that made no reference to the pharmacist’s complex role in assisted suicide and euthanasia. The complexities involved in the roles of pharmacists were unrecognised, unvalued, ignored, simplified or maybe not understood. The individual pharmacist was excluded from the “conscientious objection” section of the Bill.

Her/his human and constitutional right to freedom of conscience was not acknowledged or protected. The consequences of this exclusion would have resulted in vulnerable individual pharmacists and a vulnerable profession.

Vulnerability

Vulnerability can be defined as a lack of autonomy and independence, bodily and psychological insecurity, marginalised or deviant status, or lack of acknowledgement within society. Vulnerable groups are exposed to discrimination, intolerant attitude, and subordination. Vulnerability is usually seen as an inherent quality of certain social groups (but not others). However, it has many dimensions and might be attributed to relatively ‘powerful’ groups. Doctors, pharmacists and nurses,ie, so-called powerful groups, are rarely characterised as vulnerable, but within certain circumstances, they can be recognised as vulnerable. Euthanasia and assisted suicide may

be depicted as no more than an individual patient’s wish. This ignores the presence of vulnerable professionals in the process. Doctors, pharmacists and nurses are individually independent moral agents who must make his/

her independent and separate autonomous response, be required to justify it when asked, and take due responsibility for it.

As healthcare systems and societies are changing, the social positions of doctors, pharmacists, nurses and patients within them are changing too. In the past, clinical experts’ authority and patients’ autonomy have been in conflict. The current patient-centered/personcentered model of healthcare aims to establish egalitarian relationships between patients and professionals and other healthcare providers.

However, the vulnerabilities of doctors, pharmacists and nurses would often appear to be invisible in the euthanasia and assisted suicide debates that include a focus on the personal autonomy of the patient. The relationship of the physician/pharmacist/nurse with the patient is a moral equation with rights and obligations on both sides and it must be balanced so that physicians/pharmacists/nurses and patients act beneficently toward each other, while respecting each other’s autonomy. Beneficence and autonomy must be mutually reenforcing if the patient’s good is to be served, if the physician/pharmacist/nurse’s ability to serve that good is not to be compromised, and if their moral claim to autonomy and the integrity of the whole enterprise of medical ethics are to be respected.

Vulnerability is part of the human condition and is an all-pervasive phenomenon in healthcare. We as pharmacists can understand our humanity only by recognising our universal vulnerability and interdependence. ‘No man is an island.’ The Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights (UDBHR) text contains the first statement of bioethical principles accepted by governments (Box 2).

Experience in other countries shows that legalising assisted suicide, euthanasia or both can have a profound impact on pharmacy practice. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society in the policy statement ‘Assisted Dying’ advises that policy-makers need to recognise and be aware that the role of pharmacists goes far beyond supply of the required medication. Pharmacists in Ireland provide professional services in a variety of settings in response to local, national and international needs and priorities, with a focus on populations and/or individual patients, ie, palliative/hospice care, long-term care, intellectual disability care, hospitals, community, HIQA, HPRA, regulation, Department of Health, academia, research, education and the pharmaceutical industry.

Pharmaceutical Public Health in Ireland includes services to populations, such as guidelines and treatment

protocols, medicine use review and evaluation, national medicine policies and essential medicines lists, pharmacovigilance, needs assessment and pharmaco-epidemiology, etc. Individual pharmacists and the pharmacy profession will be challenged if euthanasia and assisted suicide are legalised in Ireland.

There are many euphemisms (‘dying with dignity’, ‘medical assistance in dying (MAiD)’ ‘physician-assisted dying/suicide’, etc) used to describe the euthanasia and assisted suicide and the lethal medication process. The

following definitions are taken from the Houses of the Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice and Equality (2018) Report on the Right to Die with Dignity:

- Euthanasia: Euthanasia is an intervention undertaken with the intention of ending a life to relieve suffering. In euthanasia, the doctor or other person involved ‘acts last’; it is their action that causes death.

- Assisted suicide: The act of intentionally assisting a person to take their own life. Importantly, in assisted suicide, the person seeking to die ‘acts last’; they take the medicine/use whatever means selected that results in death. The assistance allows them to do so.

One concerning feature of the Dying with Dignity Bill 20203 is that it does not mention euthanasia or assisted suicide or lethal medications in any of the qualifying criteria or provisions. Instead, it uses confusing phrases such as ‘assistance in dying’, ‘the prescription of substances that can be orally ingested’, and ‘the substance or substances may be administered’.

‘Euthanasia’ and ‘assisted suicide’ are the terms used throughout the following reflective article

There are many potential sources of vulnerability for individual pharmacists, and each constitutes a different, overlapping layer. Vulnerability is not static or fixed, with many sources of vulnerability overlapping in different situations arising from our human condition. Different elements can locate a person (ie, pharmacist) in a situation of personal and/or professional vulnerability. Vulnerability is dependent on the different positions we occupy in social space, or in the way we are supported (or not) by our social institutions, ie, legislation, professional organisations and regulation. “Vulnerability is experienced uniquely by each of us.” The vulnerabilities of pharmacists if euthanasia and assisted suicide are introduced to Ireland can be reflected on in relation to: (1) personal vulnerability; (2) professional vulnerability; (3) societal vulnerability; and (4) lethal medication vulnerabilities.

1. Personal Vulnerability

Pharmacists will be at the vortex of some of society’s most controversial moral dilemmas. Pharmacists are highly-trained professionals with moral, ethical and legal accountability. The role of pharmacists in the pharmaceutical care/medication use process at the end of life is often ignored, written out or overlooked.

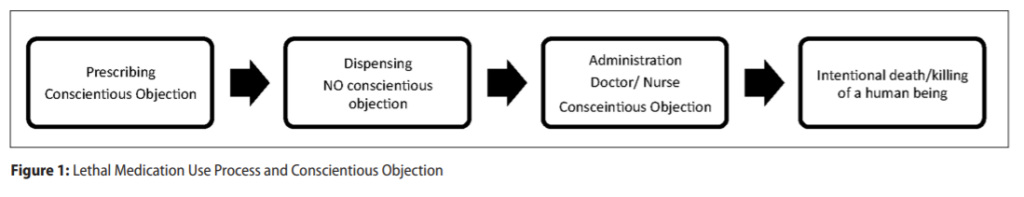

All forms of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide require lethal medications dispensed by pharmacists. In many jurisdictions where euthanasia/assisted suicide are legalised/allowed, doctors and nurses are included in ‘conscientious objection’ legislative protections. In contrast, pharmacists worldwide have fallen through the cracks of the legal protection of conscience, and are often excluded from protection of their moral and human right to freedom of conscience and the derived right of ‘conscientious objection’ (Figure 1).

Conscience is defined by the Cambridge Dictionary (2021) as “that part of you that judges how moral your own actions are and makes you feel guilty about bad things that you have done or things you feel responsible for”

Pharmacists are vulnerable when their personal dignity as human beings is not acknowledged and the treatment they receive in regulation and legislation is not equal to that which doctors and nurses receive. All three professions are part of the lethal medication use process. Euthanasia and assisted suicide cannot occur without the provision of lethal medications/lethal doses of medication.

Many pharmacists may have a moral and/or ethical objection (for a number of reasons) to participation in a process that results in the intentional ending of a human life.

2. Professional Vulnerability

Pharmacy as a profession is orientating itself towards patient interaction. Pharmacists are required to make difficult decisions in light of their personal judgement and they are also assuming responsibilities for patient outcomes. Pharmacy has been affected significantly by societal transformations such as mass manufacturing of pharmaceuticals, widespread availability of drug information, and inclusion of pharmacists on healthcare teams. As such, its traditional roles, such as compounding, dispensing and advising, have been challenged.

Pharmacy will be vulnerable in the future if the profession loses ground to other health professions in understanding identity challenges in pharmacy. These vulnerabilities will be magnified when pharmacists are unaware that their human rights (ie, freedom of conscience) are moral entitlements that every individual in the world possesses simply by virtue of the fact that he or she is a human being. In claiming our human rights, we are making a moral claim.

Human rights belong to individual pharmacists — to ensure that every individual pharmacist can live a life of dignity and a life that is worthy of a human being.

Moral distress involves a threat to one’s moral integrity — that sense of wholeness and selfworth that comes from having clearly-defined values (ie, the value of human life) that are congruent with one’s perceptions and actions. Ethical dilemmas that may arise for pharmacists speak to the ethical justifications when considering alternative courses of action (clinical, legal and spiritual components).

Moral distress begins after the fact, and involves the social and organisational issues at play, along with a consideration of personal feelings and explorations of accountability and responsibility. If pharmacists and pharmacy organisations are to remain true to stated core values, finding solutions to moral distress is an ethical imperative.

Moral distress is a growing problem in healthcare. It has been defined by Andrew Jameton in 1984 as the inability of a moral agent, ie, a pharmacist, to act according to his or her core values and perceived obligations due to internal and external constraints. Constraints such as risk of litigation, peer pressure, education by senior colleagues, practice norms, pressure by patients and pressure from regulatory bodies have been hypothesised as drivers for defensive practice by pharmacists. A broad definition of defensive practice is “deviation from sound medical practice that is induced primarily by a threat of liability”

Irish pharmacists and pharmacy students are excluded from protection of their moral and human right to freedom of conscience and conscientious objection in the Health (Regulation of Termination of Pregnancy) Act 2018. Doctors and nurses and their students are included in the Conscientious Objection section of the Act. This unequal treatment makes individual pharmacists and the profession of pharmacy vulnerable. Unequal treatment of pharmacists is also evident in the Conscientious Objection section of the Dying with Dignity Bill 2020.

This is unequal, unjust and unfair and perpetuates the vulnerability of pharmacists and pharmacy. If doctors and nurses (and others) are included in the conscientious objection section, pharmacists should also be included.

The inclusion of one group in legislation excludes all groups not included. Politicians, legislators, regulators, society, or other professions may not recognise the value of pharmacists or understand the contributions of pharmacists to healthcare and public health in Ireland and their pivotal role in the lethal medication process. It is unclear to the vulnerable Irish pharmacist if legislative and regulatory activities affecting pharmacy practice (including new and proposed policy changes that impinge on the moral values of the individual pharmacist, such as the value of human life) are being monitored by any professional pharmacy organisation.

Research into defensive practice in the pharmacy profession should inform future policy and legislation, which both protects vulnerable patients and empowers vulnerable pharmacists to provide high-quality care “without fear of litigation motivating unnecessarily conservative approaches to practice”

Morality is that higher standard that helps each pharmacist to form her/his ethical standard of conduct. Moral philosophy drives ethics, because ethics is the systematic study of moral conduct and moral judgement. Codes

of ethics should be based on moral foundation (not legal foundation or public opinion). Codes of ethics are fallible because people are fallible.

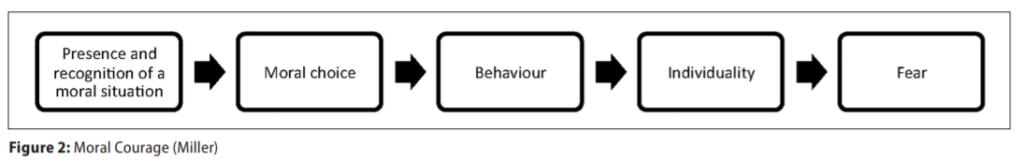

Ethical codes cannot encompass what all individuals in a profession believe. Ethical codes that encompass true conscience clauses protect individuals from having to act against their own moral values and beliefs. Societies that deny the moral right to freedom of conscience, and thereby expect policy implementers such as individual pharmacists to lead morally-divided lives, are presented with a moral problem. Moral courage as defined by Miller has five major components: Presence and recognition of a moral situation; moral choice; behaviour; individuality; and fear (Figure 2).

Pharmacists operate within a highly-regulated environment and are bound by strict legal frameworks and codes of professional conduct. This, combined with pharmacy having a strong ethical grounding, creates the potential for moral distress to occur in the profession. Understood as a psychological and emotional response to the experience of moral wrongdoing, there is evidence to suggest that — if unaddressed — it contributes to staff demoralisation, desensitisation and burnout and, ultimately, to lower standards of patient safety and quality of care.

Professional work is unique in society, because it exists in areas where there are no clear-cut ‘right’ answers — professionals work in complex environments, dealing with complex problems. They must act and make decisions based on judgment, wisdom, morality, ethics, and intuition. Professional selfidentity is a hallmark of professional status and an important part of what motivates and supports practice. Gregory and Austin found that in times of crisis, when it matters most, pharmacists may not identify as pharmacists and they may have weak or incomplete professional self-identity formation. Weak or incomplete professional self-identity formation in the pharmacy profession may adversely affect patient care and pharmacy practice.

Negative defensive pharmacy practices may include increased referral to other healthcare practitioners, overly-conservative safety-netting strategies, or avoidance of treatment of certain conditions or supplying certain services, especially for high-risk patients.

Society has a social interest in pharmacists acting as gatekeepers to prevent the illicit use of prescription medications and to prevent harm to patients. Society desires pharmacists to be conscientious, but denies them legal protection of their human right to freedom of conscience, ie, wants them to be conscientious but not to have a conscience. This contradiction results in vulnerabilities for the pharmacist, as most professionals are not required to abandon their morals in the workplace. Pharmacy is vulnerable to becoming a robotic profession if pharmacists are dehumanised when required to leave their morality (‘Thou shalt not kill’) and/or religion at home, when they go to work.

Some US trainee physicians experiencing moral distress have reported developing detached and dehumanising attitudes towards patients as a coping mechanism, which may contribute to a loss of empathy.

Professional pharmacy organisations in many jurisdictions educate, support, and unify members. They also help influence and monitor pharmacy-related legislation, promote research in the field and standardisation, and strive to improve patient care. In the US, state pharmacy associations fight against legislation that can negatively affect pharmacies and proactively look for ways to expand pharmacy practice.

It has been suggested that revising the regulation model governing pharmacy could offer pharmacists the flexibility needed to address the individuality of scenarios encountered in practice without fear of legislative implications. US trainee physicians have described how patient autonomy and a fear of lawsuits have contributed to moral distress.

3. Societal Vulnerability

International conventions attach equal importance to freedom of thought, of conscience and of religion. These freedoms are inextricably bound-up with freedom of expression, assembly and association, since without the latter, the former cannot be properly exercised. These freedoms are not always recognised under national constitutions and even if these rights are guaranteed under the constitution, it may be that the courts do not enforce them, or that groups in society actively impede their exercise or even persecute those who seek to have their right to exercise freedom of conscience recognised.

When excluded in legislation from protection of their moral and human right to freedom of conscience, pharmacists are vulnerable. In a resolution adopted in 2014, the European Parliament has emphasised that “the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion is a fundamental human right”.

Upholding the moral right to freedom of conscience is an essential principle of liberal democratic life that is reaffirmed in the courts to the greatest extent possible. However, such accommodation needs to be balanced against the rights of others and the duties of the state. It is reasonable to expect freedom of conscience/ conscientious objection claims to be facilitated by the pharmacy profession and society, given that pharmacist professionals are held to higher professional and private moral standards than most other professions. Indeed, conduct in a pharmacist’s private life can be cause for professional censure.

“Make sure that your conduct at all times, both inside and outside your work environment, ensures public trust

and confidence in the pharmacy profession.”

Opinions, preferences, etc, should not determine moral standards. Societal moral standards originate law. When people (ie, public opinion) abandon absolute moral standards, for example ‘Thou shalt not kill’, previously unacceptable behaviour (ie, intentional killing) is seen as acceptable. This results in the creation of new ‘rights’ that are turned into laws that potentially infringe on the conscience of those who adhere to the absolute moral standard.

For a pharmacist to hold a sincere moral conviction is to say, ‘here I stand, and I can do no other’. Those who can best claim to be conscientious, Prof Kimberley Brownlee has argued, are those who are willing to be seen and who do not evade the risks of non-participation. From a societal public health point of view, accommodating freedom of conscience/conscientious objections offers a way to keep policy implementers such as pharmacists in their roles, while maintaining their moral integrity.

In a situation where euthanasia and assisted suicide (in its current form) is introduced in Ireland, pharmacists in all working environments (pharmaceutical industry, community pharmacy, hospital pharmacy, palliative care pharmacy, long-term care, care of people with disabilities, including intellectual disabilities, general practice pharmacists, HPRA, HIQA, pubic health, etc,) will be part of the lethal medication use process. In particular, Irish hospital pharmacists will be interested to note that the Second Annual Report on Medical Assistance in

Dying in Canada 2020 details Canadian pharmacist reports that provide information about the type of pharmacy where euthanasia and assisted suicide medications were dispensed.

(Both practitioners and pharmacists in Canada are required to report on euthanasia and assisted suicide:

The practitioner when there is a written request received for euthanasia and/ or assisted suicide, and the pharmacist when euthanasia and assisted suicide medications drugs are dispensed.) Each jurisdiction in Canada has different guidelines regarding the dispensing of these types of medications. In Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, Manitoba and Saskatchewan, euthanasia and assisted suicide medications are dispensed exclusively by hospital pharmacies. In Québec, the majority of drugs (98.9 per cent) are dispensed by hospital pharmacies, with the remainder (1.1 per cent) being dispensed by pharmacies located within long-term care residences.

The European Statements of Hospital Pharmacy reflect the importance of the hospital pharmacist as a key stakeholder within the hospital teams for providing optimal and safe patient care. The overarching goal of the hospital pharmacy service is to optimise patient outcomes through working collaboratively within multidisciplinary teams in order to achieve the responsible use of medicines across all settings. Pharmacists will be morally challenged and professionally vulnerable if they do not consider (for any number of reasons) the provision of lethal medications to be safe and optimal patient care.

4. Lethal Medication Vulnerabilities

Many healthcare professionals (including pharmacists), politicians and members of the general public may be under the impression that euthanasia and assisted suicide would be achieved by the administration of ‘a pill’. Promoters of assisted suicide and/or euthanasia often suggest that the use of medications during the assisted dying process results in a painfree, dignified death for all. This is not the case. Modern medicine cannot guarantee a painfree death (natural or intentional) for all.

The difficulties and complications of medication administration during the assisted suicide/euthanasia lethal medication process are rarely mentioned by those promoting the introduction of assisted suicide and/or euthanasia to intentionally end a human life. Patients and professionals are vulnerable in the process. It is important that the ‘correct’ medications are chosen. However, there are no drugs or devices that have been approved by the US FDA for assisted suicide or euthanasia. Failure to use the ‘correct’ medications in the assisted suicide and/or euthanasia process may lead to traumatic situations, such as an extended time to death or awakening of the patient, causing distress for the patient and the attending family and healthcare providers. One-third of cases identified in a study in 2013 involved the use of non-recommended drugs, mainly opioids or benzodiazepines.

The authors suggested that: (a) Some physicians may overestimate the actual lethal effect of these drugs in persons at the very end of life; and (b) some physicians use drugs that are not associated with the recommended euthanasia procedure but with ‘palliative sedation’ as a strategy to reduce cognitive dissonance, that is, the mental discomfort experienced by a person with conflicting attitudes, as some clinicians find ‘palliative sedation’ emotionally less burdensome to perform than euthanasia.

There is currently an international scarcity of lethal medications suitable for oral administration during an assisted suicide. Self-administration of lethal medication for assisted suicide in Canada is permitted in all jurisdictions except for Québec. The Second Annual Report on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada 2020 indicated that there were fewer than seven reported cases of selfadministered lethal medications (assisted suicide) across Canada. All other intentional deaths were therefore euthanasia, where the doctor or the nurse are the final actor who administers the lethal medication.

A combined total of 7,595 assisted suicide and euthanasia deaths were recorded in Canada in 2020. The total number of assisted suicide and euthanasia deaths reported in Canada since the enactment of legislation is 21,589. Annual growth in assisted suicide and euthanasia cases has been steadily increasing each year in Canada and in particular, rising 34.2 per cent (2020 over 2019), from 26.4 per cent (2019 over 2018).

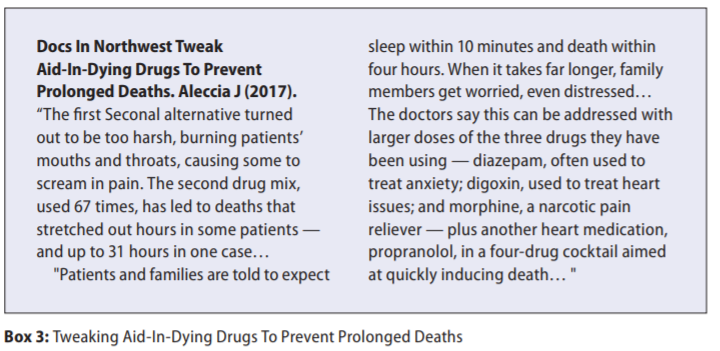

Oral assisted suicide was used only seven times in Canada during 2020. In a number of jurisdictions, the usual drugs used during assisted suicide are 90-100 x 100mg secobarbital tabs, dissolved in liquid and swallowed quickly with an antiemetic pre-med, usually given to prevent vomiting. There is no international consensus on either the medications or the protocols for oral administration, nor a comprehensive understanding of the potential side-effects and complications associated with different regimens. The quality of evidence for ‘optimal’ assisted suicide medications is low.

It is recognised that any suggested recommendations can only be informed by the global but

generally anecdotal experience.

On occasions, when oral barbiturate drugs are available internationally and administered during assisted suicide, there are reports of patients being unable to self administer a complex cocktail of lethal medicines. Family members have reported having to scrape powder from 100 plus capsules with toothpicks to produce bitter powder to be mixed with sugar syrup. Medication for nausea and vomiting must be consumed before and during the process. In some countries, lethal cocktails have been ‘experimented’ with, due to difficulties sourcing licensed medicines for the purpose of assisted suicide and/or euthanasia, (Box 3).

A number of medicines used in assisted suicide and/or euthanasia were previously used in executions. (Pentobarbital became unavailable after drug-makers blocked its use in American death penalty executions.) Use of medicines during executions has been described as ‘inhumane’, with reports of people feeling ‘burning’ sensations throughout their bodies prior to death. A scoping review of the 163 studies that included technical summaries, institutional policies, practice surveys, practice guidelines and clinical studies that describe assisted suicide and/or euthanasia provision in adults, identified complications that may cause the patient, family and provider distress.

These included prolonged duration of the dying process, difficulty in obtaining intravenous access, and difficulty in swallowing oral agents. In the Oregon Death with Dignity programme (1998-2016), there are reports of one patient having required up to 104 hours to die, at least six patients awoke after ingesting drugs, and for many patients, it is “unknown” whether complications occurred.

Discussion

No medical association oversees assisted suicide or euthanasia, and no government committee helps fund research. In American states where the practice is legal, state governments provide guidance about which patients qualify, but say nothing about which drugs to prescribe. Research on this issue takes place on the margins of traditional science. It’s a part of medicine and pharmacy that is ‘practiced in the shadows’. Secrecy laws protect the identity of participating physicians, pharmacists, and drug suppliers, resulting in reduced transparency. Pharmacists providing medication for euthanasia/assisted suicide have been described as undertaking the role of an “accomplice”.

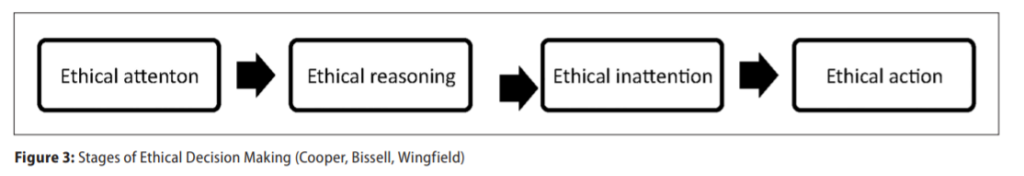

Pharmacists and the pharmacy profession must not be passive in the upcoming national debate concerning the introduction of euthanasia and assisted suicide to Ireland. Euthanasia and assisted suicide are a matter of life and death for vulnerable people and people at a vulnerable time in their lives. ‘Ethical passivity’ is a term used to describe pharmacists who were ethically inattentive, who display limited forms of ethical reasoning, prioritise legalistic selfinterest, and are unable to act. Such ‘ethical passivity’ is argued to be inimical to healthcare practice and may be detrimental both to the welfare of vulnerable patients, and for pharmacy. Pharmacists have indicated that they were unable at times to do what they believed they should do and that when this happened, they simply did nothing or allowed supervening acts or the intervention of others to resolve an ethical situation. (Figure 2).

Moral distress can be distinguished from the concept of ethical dilemmas. Ethical dilemmas concern two or more courses of action which are in conflict (and will potentially have both positive and negative consequences) but where each action can be defended as viable and appropriate. In contrast, with moral distress, one action only is preferred by the pharmacist, but that pharmacist feels blocked from enacting that action by factors outside of the self.

There will be no going back for pharmacy or Irish society if assisted suicide and euthanasia are introduced to Ireland. The life or death of the individual will be at stake. The moral position and the freedom of conscience of the vulnerable pharmacist will be engaged. Vulnerable patients, people at a vulnerable time in their lives and vulnerable professionals will be at risk. Pharmacists without legal protection of their moral and human right to true freedom of conscience, and limited awareness among other professionals and the public of their complex role, will be one of the most vulnerable.

Moral dilemmas will be experienced by pharmacists when their moral and/or professional autonomy is challenged by the behaviour/demands of patients and other health professionals. Vulnerable pharmacists will have to choose a morally justifiable action (‘Thou shalt not kill’), among several suboptimal action/inaction options.

Vulnerability is a shared condition in healthcare and this has an impact on the way of understanding vulnerability in regard to the relationships among patients, healthcare professionals, and institutions. Vulnerability can lead us pharmacists to better understand our shared condition and the effect this condition has on relationships and moral actions/ inactions. Reflecting on the vulnerability of the individual pharmacist and the pharmacy profession demands a response, generating responsibility and various wide-ranging implied obligations.

These obligations are especially important from the perspective of pharmacists, healthcare professionals, institutions and the state. Vulnerability positions us in relation to each other as human beings and also suggests a relationship of responsibility between the state and the individual pharmacist. The success of a democracy depends on everyone contributing to its goals of prosperity, security, and non-tyranny.

It is crucial that pharmacists, student pharmacists, and pharmacy technicians get involved in advocacy efforts at all levels of government so as to positively affect the future of this vulnerable profession and to raise awareness of the complexities in the role of the pharmacist.

References on request