Mr Kevin Roche, Mr Anthony Maher and Dr Eimear Morrissey write about the potential for pharmacist prescribing to exacerbate the problem of antimicrobial resistance

From January 2026, Irish pharmacists have been able to prescribe antibiotics for common conditions. On the surface, this appears to be a practical response to GP shortages and rising demand in primary care. However, international experience suggests that without careful safeguards, expanding prescribing rights risks exacerbating an already serious problem: Antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Understanding antimicrobial resistance

AMR occurs when micro-organisms adapt and no longer respond to medicines that were previously effective, making infections harder to treat. A key driver of AMR is excessive antibiotic use, particularly for respiratory and urinary tract infections that are often viral and would resolve without treatment. Although antibiotics are life-saving when used appropriately, unnecessary prescribing accelerates resistance and undermines their effectiveness.

Why clinicians prescribe antibiotics

In primary care, prescribing decisions are rarely straightforward. One of the main challenges for GPs is diagnostic uncertainty, especially when it is unclear whether an infection is bacterial or viral and rapid diagnostic tests are unavailable. To avoid the risk of missing a serious bacterial infection, clinicians may prescribe antibiotics ‘just in case’, even when the indication is uncertain.

A doctor’s previous experiences and fear of complications if antibiotics are not prescribed can strengthen the tendency to use them. Time pressures during consultations also influence decisions, as it is often quicker to prescribe antibiotics than to explain why they are unnecessary. These factors show that clinical judgment is shaped not only by medical evidence, but also by the

The role of patient expectations

These pressures are often compounded by patient expectations. Expectations for antibiotics, perceived demand, and the potential for conflict when requests are declined can strongly influence decisions. Some prescribers may give antibiotics to maintain patient satisfaction or protect the therapeutic relationship, even when it is not medically necessary. When people feel unwell, they want reassurance. And when they feel the ‘same type of unwell’ that previously led to a prescription, they often want the prescription again.

Research from several high-income countries shows that patient expectations remain a powerful driver of antibiotic use, with many prescribers reporting pressure to meet those expectations (Fletcher-Lartey et al, 2016; Kasse et al, 2024; Sirota et al, 2017).

Organisational and system influences

Alongside these clinical pressures, wider organisational and system factors also influence prescribing decisions. Local prescribing guidelines, antimicrobial stewardship programmes (which aim to promote the responsible use of antibiotics) and an awareness of AMR can encourage more careful use of antibiotics. However, adherence to these initiatives varies widely and is strongly influenced by practice culture.

Practice culture refers to the shared norms and informal rules that guide behaviour within a clinical setting. In some practices, prescribing decisions are rarely discussed openly, and clinicians may rely on habitual approaches or implicit expectations about acceptable practice, particularly when managing uncertainty. In contrast, practices that encourage peer discussion, case review, and audit and feedback tend to normalise more conservative prescribing and provide reassurance when antibiotics are withheld. Leadership and a shared commitment to stewardship further reinforce these norms, while high workload and competing priorities may limit opportunities for reflection.

Extending prescribing rights to pharmacists

Once pharmacists are empowered to prescribe, they too can become part of this cycle that sustains unnecessary antibiotic use. This cycle begins with patient expectations for antibiotics, continues with prescribers feeling pressure to meet those expectations, and is reinforced each time a prescription is issued. Over time, antibiotics become seen as the default response to common illnesses.

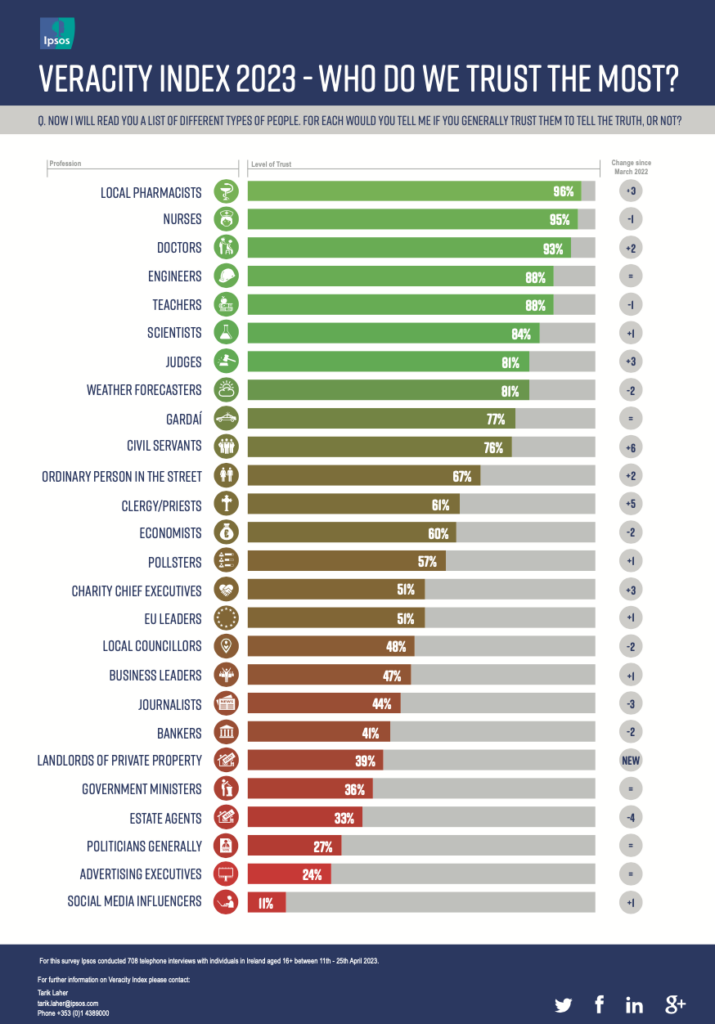

Pharmacists are among the most trusted and accessible health professionals. Patients may even view medicines obtained from a pharmacist as safer or less potent, partly because pharmacists have traditionally been restricted in what they can supply. Yet this perception overlooks the international evidence. Where pharmacist prescribing has been introduced without strong safeguards, it has often contributed to increased antibiotic use. Pharmacists therefore occupy a pivotal position — they can either help break this cycle through responsible prescribing, or they could become conduits for overprescribing.

Lessons from abroad

Experience from other countries offers important warnings. In New Zealand, trimethoprim was reclassified in 2012 to allow pharmacists to supply it for uncomplicated urinary tract infections. Despite strict eligibility criteria, overall antibiotic use, including trimethoprim, increased significantly. Researchers attributed this to demand-driven supply, with antibiotics often provided for self- limiting conditions (Gauld et al, 2017).

In Canada, provinces such as Saskatchewan and Ontario introduced pharmacist prescribing for minor ailments to expand access and reduce system pressure. Service evaluations found high patient satisfaction and some cost savings. But they also raised concerns: When pharmacist remuneration was tied directly to prescribing decisions, the risk of overprescription increased (Mansell et al, 2015).

In the United Kingdom, evaluations of community pharmacy-led urinary tract infection services have shown that a substantial proportion of women presenting with urinary symptoms were treated with antibiotics through these schemes, with treatment rates comparable to general practice management rather than demonstrating a reduction in overall antibiotic use.

For example, in a community pharmacy test-and-treat service, approximately three-quarters of consultations for uncomplicated lower urinary tract infection resulted in antibiotic treatment (Thornley et al, 2020; Swart et al, 2024; Booth et al, 2013).

The Irish challenge

In Ireland, the challenge will be ensuring that improved access does not come at the cost of increased antibiotic use. With clear protocols, access to diagnostic tools, and strong oversight, pharmacists could become valuable allies in the fight against

AMR. They are well placed to educate patients, reinforce self-care, and provide safety-netting advice. But success depends on resisting the easy route of ‘more antibiotics, faster’.

The story of AMR is a story of good intentions colliding with human behaviour. Clinicians prescribe ‘just in case’. Patients push for reassurance. Health systems under pressure seek quick fixes. Ireland’s new pharmacy scheme sits at the crossroads of all these forces. Antibiotics remain one of the most important tools in modern medicine. Protecting them requires ensuring that every prescription is truly necessary, regardless of who writes it.

Mr Anthony Maher, MPSI is a registered pharmacist and a HRB PhD SPHeRE Scholar researching antibiotic use through behavioural economics in the School of Psychology, University of Galway

Dr Eimear Morrissey is a Lecturer in Evidence- Based Healthcare within the College of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences at the University of Galway

Mr Kevin Roche is an Irish Research Council funded PhD SPHeRE scholar researching antibiotic prescribing in Irish General Practice in the School of Psychology, University of Galway

References

1. Booth, Jill L, Alexander B Mullen, David Am Thomson, et al, 2013. ‘Antibiotic Treatment of Urinary Tract Infection by Community Pharmacists: A Cross-Sectional Study’. British Journal of General Practice 63 (609): e244–49. https://doi.org/10.3399/ bjgp13X665206.

2. Fletcher-Lartey, Stephanie, Melissa Yee, Christina Gaarslev, and Rabia Khan, 2016. ‘Why Do General Practitioners Prescribe Antibiotics for Upper Respi- ratory Tract Infections to Meet Patient Expectations: A Mixed Methods Study’. BMJ Open 6 (10): e012244. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012244.

3. Gauld, Natalie J, Irene SL Zeng, Rosemary B Ikram, Mark G Thomas, and Stephen A Bue- tow, 2017. ‘Antibiotic Treatment of Women with Uncomplicated Cystitis before and after Allowing Pharmacist-Supply of Trimethoprim’. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy 39 (1): 165–72. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0415-1.

4. Kasse, Gashaw Enbiyale, Judy Humphries, Suzanne M. Cosh, and Md Shahidul Islam, 2024. ‘Factors Contributing to the Variation in Antibiotic Prescribing among Primary Health Care Physicians: A Systematic Review’. BMC Primary Care 25 (1): 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-023-02223-1.

5. Mansell, Kerry, Nicole Bootsman, Arlene Kuntz, and Jeff Taylor, 2015. ‘Evaluating Pharmacist Prescribing for Minor Ailments’. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 23 (2): 95–101. https://doi. org/10.1111/ijpp.12128.

6. Sirota, Miroslav, Thomas Round, Shyamalee Samaranayaka, and Olga Kostopoulou, 2017. ‘Ex- pectations for Antibiotics Increase Their Prescribing: Causal Evidence about Localised Impact.’ Health Psychology 36 (4): 402–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/ hea0000456.

7. Swart, Ansonette, Shalom I. Benrimoj, and Sarah Dineen-Griffin, 2024. ‘The Clinical and Economic Evidence of the Management of Urinary Tract Infec- tions by Community Pharmacists in Women Aged 16 to 65 Years: A Systematic Review’. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy 46 (3): 574–89. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s11096-023-01679-6.

8. Thornley, Tracey, Charlotte L Kirkdale, Elizabeth Beech, Philip Howard, and Peter Wilson, 2020. ‘Evaluation of a Community Pharmacy-Led Test- and-Treat Service for Women with Uncomplicated Lower Urinary Tract Infection in England’. JAC-An- timicrobial Resistance 2 (1): dlaa010. https://doi. org/10.1093/jacamr/dlaa010.