Terry Maguire reflects on the life and work of one of his heroes

“I truly believe that managing people, instead of leading them, is wrong and has resulted in too many dysfunctional and unhappy workplaces.”

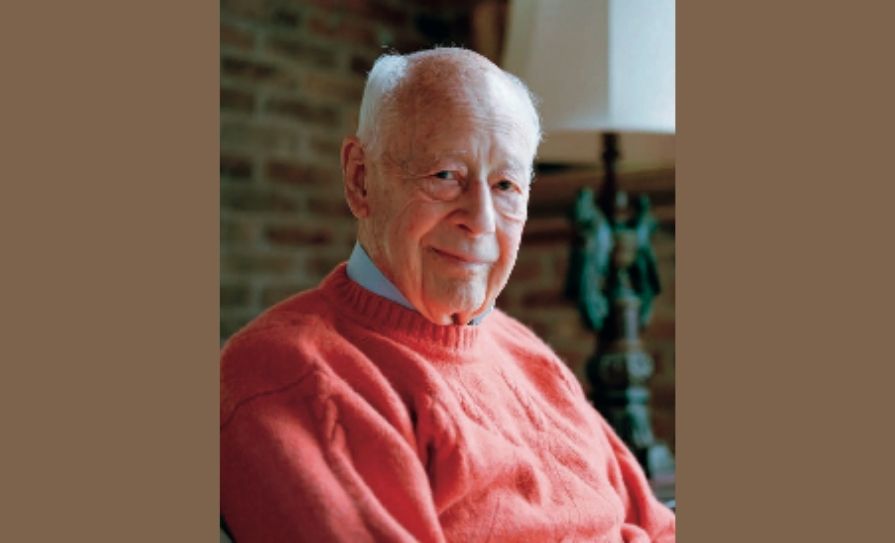

Charles Handy 1932-2024

An obituary in The Irish Press in December alerted me to the death of my great hero Charles Handy. His management books were critical to my personal and professional development from the late 1980s onwards, and they still inspire me. He was much more than the myriad management gurus selling their wares at that time. He was a management theorist and social philosopher and his impact was significant, if now largely forgotten. And, of course, he was Irish.

I was asked in the 1990s by the Editor of the Chemist and Druggist magazine to write a book version of my weekly management series. Re-reading this recently, I was struck by the influence Charles had; on me, on my management views and my personal philosophy of life, and hopefully I still retain these. Two areas that profoundly affected me were his views on business strategy and people management.

Business strategy

Charles studied successful businesses and successful people, and his analysis was that successful businesses are only created by people who have a clear and powerful vision. This was the core to his famous book The Empty Raincoat.

Passion, he was convinced, only truly comes from a strong vision. You work hardest when you know why you’re doing it. The vision might involve setting up a new business whose purpose is to deliver a personal vision. But to continue being successful, the vision must be reset every 10 years or so. New visions are needed to keep the company going forward.

A vision won’t just happen; it needs to be purposefully put in place. This involves detailed analysis of the business, those who work in it, and the environment in which it operates. The process of creating a vision takes considerable time and resources, and this is perhaps why few of us bother, and why most family businesses fail after three generations.

To create the right kind of vision, we need to begin with the ‘Why?’ — the purpose. Purpose for an organisation is vital and is set out in its Mission Statement. These are common accessories nowadays and, when right, can be a powerful determinant of future direction and central to creating the motivation to move forward. The Mission Statement should address the deep underlying philosophy of why this business exists in the first place; the things beyond profit. Too often, lip service is paid to a poorly written Mission Statement, with resultant dire outcomes.

Defining a personal purpose or business purpose can be difficult. For the individual, this is the realm of spirituality, the ‘meaning of life’ stuff, finding out what is really important. And no-one was better positioned to do this than the oil executive whose father was a priest. This was the core of his book Hungry Spirit.

Charles Handy suggested writing your eulogy. Imagine yourself attending your own funeral. Your friends, family, peers and work colleagues are all there paying their last respects; well, you hope they are. You are writing a eulogy that you would like delivered by, say, a family member (not a spouse or partner — they know you too well), a work colleague, a peer or fellow professional and finally, a friend — four in all.

What would you wish each to say? Each will see you from a very different angle — the different parts that fit together to complete the real you. It is a powerful exercise if given the attention and seriousness it deserves. The essence of these four eulogies are the things which motivate you.

Managing people

Good staff are a business’s greatest asset; poor staff, its greatest liability. Charles Handy was convinced that everyone wants to do a good job, something I initially found hard to accept. He reasoned, with passionate conviction, that as long as an individual has the mental and physical ability and a willingness to undertake the tasks that make up the job, and he or she is provided with proper support and motivation, then a good job will be done.

As managers, we too often fail to appreciate really how complex people are. Emotions and feelings often usurp logic and rationality. A friendly workplace can be turned into a war zone when people, inflamed passions and poor communication get mixed in the right proportions. This is covered comprehensively in his book Understanding Organisations.

Prof Handy’s point is that too much emphasis is placed on management, and too little on motivation. Tragically, many people are in the wrong job. They either entered the wrong job by default — they had nothing else on offer — or they grew to hate their job, as it failed to fulfil their complex personal needs. Perhaps they should have been rejected at the interview stage.

Perhaps the job should have been less stressful, more challenging, and personally fulfilling. Perhaps they should have been motivated rather than censured. It’s too easy to censure staff when things go wrong. It is more challenging, yet much more productive, to praise them for a job well done.

Even in the 1980s, this was a challenging view. At that time, paternalism was the mainstay of managing employees. Staff were viewed as stupid and slothful, needing to be humiliated and threatened into doing their job. Thanks largely to Charles Handy, but others too of course, the paradigm has changed, with more emphasis on a partnership approach where the employee is empowered and facilitated to do their job through motivation.

This new paradigm reflects a wider social change; a more affluent society, more women in the workforce, more legal protection for employees, and less willingness to accept work as the raison d’etre for one’s life. This new way of managing staff is not through less management, but different management.

Handy created the concept of the Portfolio Life in his books The Age of Unreason and Beyond Certainty. Indeed, he lived the Portfolio Life from the time he left his oil industry job. Few of us now have a job for life — my own father could not have imagined anything else. To retain good employees, employers must treat them well, which means more than a fat salary. Sigmund Freud, when asked the secret to happiness, answered simply: “To work and to love.” The need to do some kind of work is human.

Few of us now have a job for life — my own father could not have imagined anything else

Central to this new paradigm is the need for managers to become leaders. If we act as leaders, we bring staff with us rather than push them from behind. Everyone wants power and control over the job they do. In this way, they can have pride in it.

The Portfolio Life

Born in Clane, Co Kildare, he grew up at St Michael’s vicarage, in the town where his father was the Protestant vicar. It was a spartan life, he recalled: “We lived in the vicarage, in the midst of the fields, a hundred yards from the beautiful country church where my father said his prayers every morning.”

Charles boarded at Bromsgrove School in Worcestershire, England, moving to Oriel College, Oxford, where he graduated in 1956 with a first-class honours in Classics, History and Philosophy. In 1956, he took a job with Shell and stayed for nine years in a post in South East Asia.

He married in 1962 and his wife Elizabeth introduced him to the world of theatre, concerts and art galleries. She went on to become a successful professional photographer as well as her husband’s agent and business manager, and the couple collaborated on a number of books, including The New Alchemists and A Journey through Tea.

When his father died in 1976, Handy was greatly impressed with the size of the attendance at the funeral, reflecting the clergyman’s spiritual influence, and he vowed to emulate this. Handy placed a strong emphasis on social ethics and values in a business context. He concentrated on writing and broadcasting and became a regular contributor to Thought for the Day on BBC, a rare lay contributor in those days.

In July 2006, Handy received an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Trinity College Dublin for his work on business management and organisational behaviour. In 1998, he received an honorary doctorate from Queen’s University Belfast.

Handy’s wife died at the age of 77 when the couple were involved in a car accident in Norfolk in March 2018. The couple are survived by their children, Kate Handy Jones, who is an osteopath, and Scott, an actor and theatre director, and four grandchildren. Other relatives include his two sisters, Margaret, a retired teacher, and Ruth, a leading figure in management studies in Ireland.

Terry Maguire owns two pharmacies in Belfast. He is an honorary senior lecturer at the School of Pharmacy, Queen’s University Belfast. His research interests include the contribution of community pharmacy to improving public health.