Recalling His Own Family History, Terry Maguire Tries To Make Sense Of The Scourge Of Addiction In All Its Insipid Forms.

I have been, for many years and mostly from an academic point of view, fascinated by addiction. Perhaps my fascination was sharpened also by a subconscious worry that a genetic curse afflicting both my maternal and paternal families, going back many generations, might too be visited on me. A great grandfather on my mother’s side was banished to America in 1907 before he “drank the farm”. Both my father’s grandparents were drunks, causing their children, including my grandfather, to be taken into care; the reason my father and his brother were life-long teetotallers. Growing up, a genetically-unrelated uncle caused such damage to our wider family that the mayhem still persists today, 40 years after his untimely death. Many Irish families have similar stories; most Irish families have been affected in some way by the scourge of addiction. In the modern age, of course, other substances and behaviours have replaced alcohol, but alcohol remains the most popular drug of choice and among the younger age groups, poly-substance abuse, including alcohol, is now the norm.

I have long tried, yet still struggle, to understand what addiction is and in particular how it so powerfully influences behaviour and how it might be managed or treated. We all know its manifestations: The alcoholic, the gambler, the drug addict, dependent on a substance/behaviour with a selfish insistence to consume, irrespective of the damage caused. What are those mental processes that create this destructive behaviour? Having understood the processes, will we eventually be in a better position to develop effective treatments?

Ian Walsh is a surgeon and QUB lecturer who at one time was treating patients in the famous kidney unit at Belfast City Hospital. In 2008, when his alcoholism became all-consuming, he was at the top of his professional career. Things fell apart. His 2021 acclaimed book The Belly of the Whale is a no-holds barred account of his fall from grace, his descent to the bottom, and his eventual recovery. This brutally honest reportage of a journey from a position of considerable privilege and responsibility to the very bottom rungs of society is as chilling as it is enlightening. Ian never feels sorry for himself. He is past making excuses for his behaviour or blaming others; he just objectively reports the journey from a comfortable, expensive home where contact with spouse, friends and family was terminated because of a passion for alcohol, through various emergency departments, to myriad rehab units, and then eventually back home again, but that home was his mother’s home, not the home he left at the nadir of his despair. His experience at his initial rehab unit was less than beneficial or therapeutic. They applied all the usual clinical and behavioural techniques. His hugely expensive subsequent residential stay at a facility was perhaps to some extent more successful, and it struck me that this success might have a lot to do with the strict and Spartan conditions imposed on the inmates, conditions staggeringly similar to my stay at boarding school in Derry in the 1970s!

A similar experience and environment in Newry was not so unsuccessful; he had to go there twice. At these rehab centres, the routine and small responsibilities, such as simply ringing the dinner bell, seemed to help but were certainly insufficient to assure long-term abstinence. Ultimately, rehabilitation is based on personal change.

As pharmacists, we know all too well that simply ‘providing’ detox chlordiazepoxide, substitution prescribing methadone, or even nicotine replacement therapy (tobacco smoking is the most lethal addiction) does little but stave-off the inevitable relapse, a recognised feature of all addictions. We also know that many people just stop without any intervention. Ian Walsh did. All the expensive inpatient rehab units amounted to nothing, but when he suffered a seizure, and in the subsequent fall incurred a serious head injury, he describes a profound change in his thinking. He had reached rock-bottom. He just made a decision to stop and he did.

Damien Thompson, author of The Fix: How Addiction Is Invading Our Lives and Taking Over Our World (2013), makes the case that addiction is not, as the current experts claim, a disease, but a distortion of the brain’s learning processes. I have covered this issue before in these pages, but I came back to it again when I read Ian Walsh’s book, and it’s worth a recap.

Sadly, those involved in addiction services are wedded to the disease model and treatments are tailored thus

The thesis promoted by Damien Thompson and by other addiction experts such as Marc Lewis and Stanton Peele is as follows: Addiction is not a disease, and drugs are not addictive; addiction is an extreme manifestation of a pretty standard brain repertoire. With good relationships and a purpose in life, we don’t become addicted to drugs or other behaviours (sex, gambling, porn). If we suffer from social exclusion, low self-esteem or we have a number of ACEs (adverse childhood experiences), then we are more likely to grab forcefully onto behaviours that instantaneously bring relief from those negative emotions; anxiety, shame, boredom that burden us. Experimentation and peer pressure usually leads us to these substances or behaviours, and bingo! We begin an emotion-behaviour loop that spirals down into a habit and then with loss of higher brain control, the bridge of the ship cannot tell the emotional tanker to wise-up and change course; the compulsion becomes ingrained.

It’s the route from one-off behaviour (experiment), to habit (regular use), to compulsion/ dependency (addiction). Dopamine seems to be the key neurotransmitter in this.

Therapy is at best hit-or-miss, and maybe not necessary at all. If you survive your addiction — and yes, it will kill many who get ensnared — those who want to change invariably do. They literally grow new neurons, so the brain works beyond the narrow focus of addiction; they identify more attractive goals become motivated to follow them, and they move on. Addiction is impaired development not brain damage, as the model of addiction suggests. Sadly, those involved in addiction services are wedded to the disease model and treatments are tailored thus.

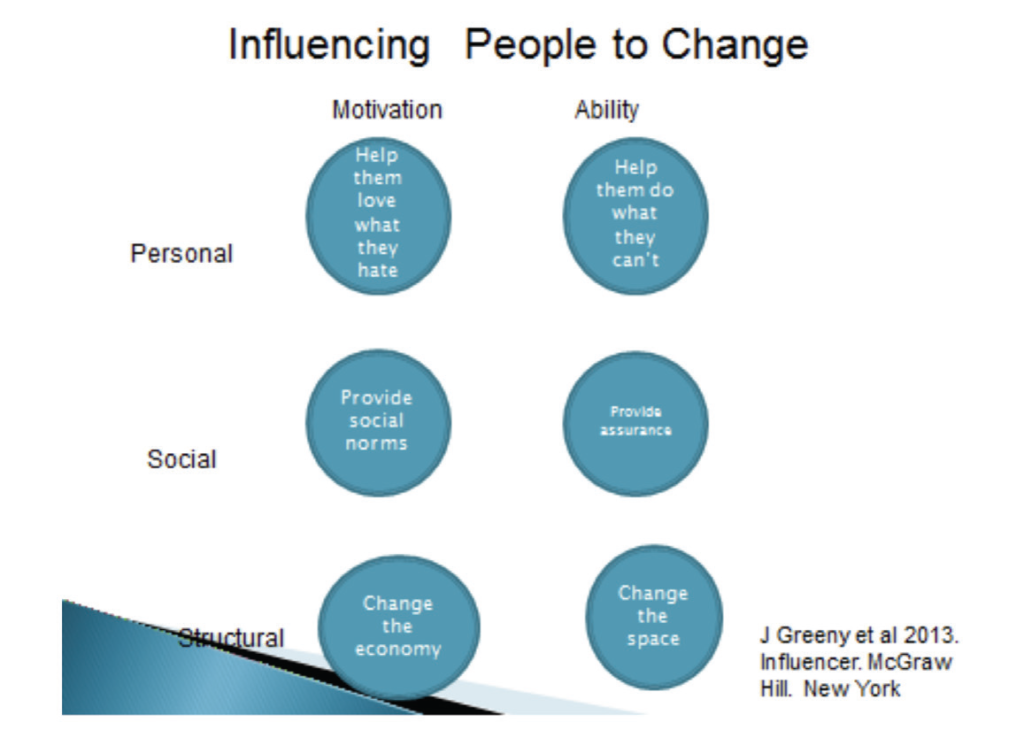

Joseph Grenny and colleagues in their book Influencer: The New Science of Leading Change, expand on this approach. They identify six domains to influence change. The matrix (Figure 1) seems a bit complex but is worthy of consideration, yet a detailed discussion is not possible in this article. There are two main domains: (1) The motivation to change; and (2) the ability to change. Most addicts don’t have the motivation to change, so giving them the ability to change is wasted. A therapist cannot motivate an individual; only the individual can do that. Changing the social circumstances and environment must be addressed. A very successful rehab project in Los Angeles, based on Grenny’s model, involves a restaurant hiring addicts and training them up to take more and more responsibility for themselves and others. Being dependent on others, and others dependent on them, means that they develop life-skills, they grow and are motivated towards new goals. Their environment is safe and access to drugs is restricted. This is an expensive model of therapy and it is beyond the current disease model, so unlikely to be funded here any time soon.

And what about me and those worrying genes? Well, Ian Walsh is convinced of a more significant genetic (nature) component to addiction as opposed to leaned behaviour (nurture), but there is little good science yet to support this. I just need to keep a close eye on my life goals, my environment and my relationships and when alcohol consumption becomes, as it does from time to time, more attractive than any of these, then I need to take personal responsibility and change course so the chute Ian Walsh slid down so spectacularly is effectively side-stepped.