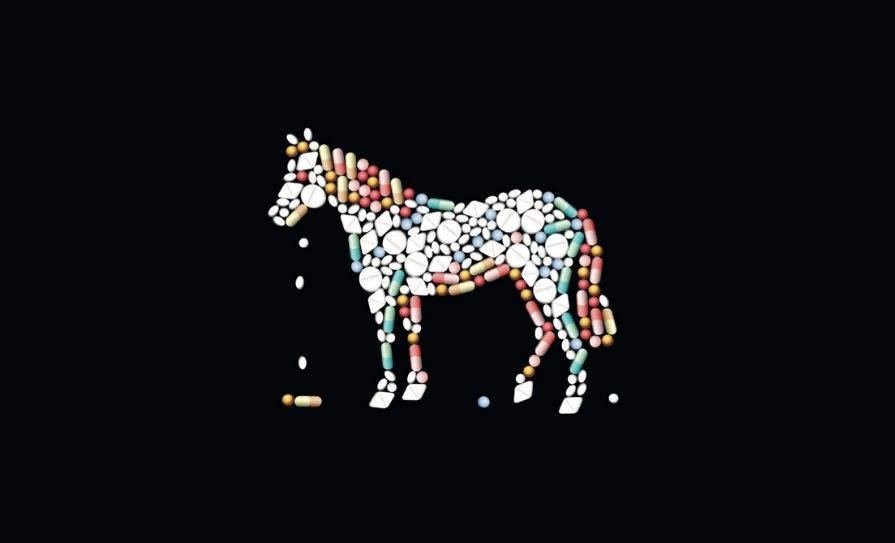

The link between veterinary medicines and illicit drug-dealing is nothing new, writes Dr Des Corrigan

The trigger for this month’s article was an alert from the US about the detection of the veterinary sedative medetomidine in street drugs, mainly but not exclusively in the fentanyl that is exercising US President Donald Trump so much.

Having written about another veterinary sedative, xylazine, in 2023, I began to wonder about a new trend. Then I remembered that the link between veterinary medicines and the illicit drug trade was nothing new, dating back as it does to the late 1990s, when ketamine emerged as a drug of abuse. Ketamine is different to the veterinary sedatives in that it is abused in its own right, whereas they, along with the anthelmintic levamisole, are used as cutting agents to enhance the profitability of street opioids, benzos, and cocaine.

Even though it is an effective anaesthetic and analgesic — at present, the Health Products Regulatory Authority (HPRA) has licensed 12 ketamine- containing or related products, five for human and seven for veterinary use — a letter to the Editor of the Irish Journal of Medical Science last year from staff of the HSE’s National Social Inclusion Office and Drug Treatment Centre highlighted the increasingly prominent use of ketamine in Ireland as part of a repertoire of stimulant and euphoria-producing ‘club drugs’ while socialising.

The letter noted that 63 per cent of respondents to a web survey had used ‘CK’ or ‘Calvin Klein’ — a mixture of cocaine and ketamine — in the past year, with episodes of a schizophrenia- like syndrome, impairment of working memory, and haemorrhagic cystitis being reported. The SPC (Summary of Product Characteristics) for the licensed products also refers to the development of tolerance and dependence.

Seizures of ketamine by gardaí have also increased, sometimes in the form of what is called ‘Tuci’ or ‘Tusi’, or ‘Pink Cocaine’. The latter rarely contains any cocaine, instead usually consisting of ketamine, MDMA, and the psychedelic stimulant 2C-B coloured pink with food dye or strawberry flavouring as a marketing ploy.

In more recent years, ketamine has been associated with ‘chemsex’, where a mix of psychoactive drugs are used to prolong sexual pleasure, used mainly by men who have sex with men. As well as ketamine, the mix commonly contains crystal meth, mephedrone, and GHB or G. Sometimes the drugs are injected — a practice known as ‘slamsex’ — which is seen as particularly harmful due to the risk of injection-related infections and STIs.

Another veterinary product is levamisole, which has been detected in cocaine samples since 2003. Here, the most recent report (2023) from the Merchant’s Quay/HSE syringe analysis project noted that 77 per cent of the 165 syringes returned to the needle exchange tested positive for levamisole. The thinking behind its use as a cutting agent is that it can boost the effects of cocaine because it is metabolised to the

amphetamine-like drug aminorex. There are no levamisole products licensed

for human use, although some 11 are approved as veterinary anthelmintics. There are concerns over its ability to cause neutropaenia and agranulocytosis, as well as cutaneous vasculitis, tissue thrombosis, and necrosis of the skin.

This harmful effect on the skin links levamisole to xylazine, which is now notorious in the US for the gangrenous skin ulceration associated with exposure to it in street fentanyl and benzos. This is apparently not like other injection-related skin wounds and infections, because life- threatening wounds are reported to occur in limbs where no injection took place, as well as in people who used non-injecting routes of administration.

Another issue is that while it causes severe respiratory depression, it does

not respond to naloxone, although this should still be given, as xylazine is usually mixed with opioids. An ?2-adrenoceptor antagonist such as atipamezole, tolazoline, or mirtazapine would work but none of these are currently licensed for reversal of xylazine toxicity in humans.

Xylazine or ‘Tranq’ has been mainly a problem in North America until recently, but according to a review conducted by the Advisory Committee on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) in the UK last year, it has been detected in nitazene samples seized in Estonia.

In fact, it is not just a cutting agent for opioids such as fentanyl, nitazenes, or heroin, but it has been found mixed with designer benzos such as bromazolam and etizolam in Canada. In the UK, xylazine has been detected in products believed by the purchaser to be benzos, THC vape liquid, codeine and tramadol tablets, heroin, and nitazenes.

The ACMD also reported 16 fatalities since 2022 in which xylazine in combination with other drugs was detected in post-mortem samples. While there is as yet no evidence of xylazine in drugs on the Irish market, it would be unwise to assume that such adulteration is not occurring, especially if the various forensic labs are not yet including it in their analytical screens.

The most recent veterinary sedative to be detected in street drug samples in many parts of the US is also an ?2- adrenoceptor agonist. Medetomidine is used mainly in cats and dogs for sedation, analgesia, and as a premedication prior to anaesthesia, often with ketamine.

The HPRA lists 10 licensed products, although some contain dexmedetomidine, which is the dextrorotatory isomer, with medetomidine being the racemic mixture. Dexmedetomidine itself is in six products licensed for human use in sedating adult ICU patients or those undergoing certain diagnostic or surgical procedures.

Xylazine or ‘Tranq’

has been mainly a problem in North America until recently

According to an alert from the US Centre for Forensic Science Research and Education (CFSRE) in 2024, dexmedetomidine is the active isomer with a potency some 200-to-300 times that of xylazine. It also has a longer duration of action. The CFSRE alert referred to mass outbreaks of overdoses due to fentanyl adulterated with both xylazine and medetomidine (called ‘rhino- tranq’ or ‘mede’) in Philadelphia, Chicago, Toronto, and Vancouver.

Last November, the Philadelphia Department of Public Health issued an alert about atypical but severe withdrawal symptoms in drug users who required ICU levels of care. These symptoms were similar to those seen with dexmedetomidine in the hospital setting and included intractable vomiting, excessive sweating, hypertensive emergency, hypoactive encephalopathy, tremor, and profound bradycardia turning to tachycardia, all of which occurred rapidly after intoxication.

That alert also mentioned 46 deaths where medetomidine had been detected between May and November. The various SPCs draw attention to reports of reproductive toxicity, highlighting that pregnant women should not be exposed to this drug. In addition to setting out the risk of respiratory depression, the SPCs state that combination with other sedatives, hypnotics, and opioids is likely to lead to enhanced sedation and cardio- respiratory effects, so using it as a cutting agent for street forms of these drugs does not seem such a bright idea. The risk of local vasoconstriction is also mentioned, which raises the possibility of increased wound prevalence in illicit drug users similar to that reported with xylazine.

Neither of the two veterinary sedatives are currently scheduled as controlled drugs, although the ACMD has recommended that the UK include xylazine under their Misuse of Drugs Act.

Notwithstanding the absence at this time of strict storage requirements, can I suggest to those pharmacists who stock xylazine or medetomidine products that they give some thought to preventing diversion of them towards street drugs.

Dr Des Corrigan, Best Contribution in Pharmacy Award (winner), GSK Medical Media Awards

2014, is an Adjunct Associate Professor at the School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences at TCD where he was previously Director and won the Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2009 Pharmacist Awards. He was chair of the Government’s National Advisory Committee on Drugs from 2000 to 2011, having previously chaired the Scientific and Risk Assessment Committees at the EU’s Drugs Agency in Lisbon. He chaired the Advisory Subcommittee on Herbal Medicines and was a member of the Advisory Committee on Human Medicines at the HPRA from 2007 to 2024. He has been a National Expert

on Committee 13B (Phytochemistry) at the European Pharmacopoeia in Strasbourg and served on the editorial boards of a number of scientific journals on herbal medicine.